The year 2019 was a study in the hopes and dreams of the very human investment markets.

Far from dispassionately evaluating the markets using artificial intelligence, investor sentiment swung between elation and making money to fears of trade wars and depression, sometimes reflecting both at once.

Full of Bull

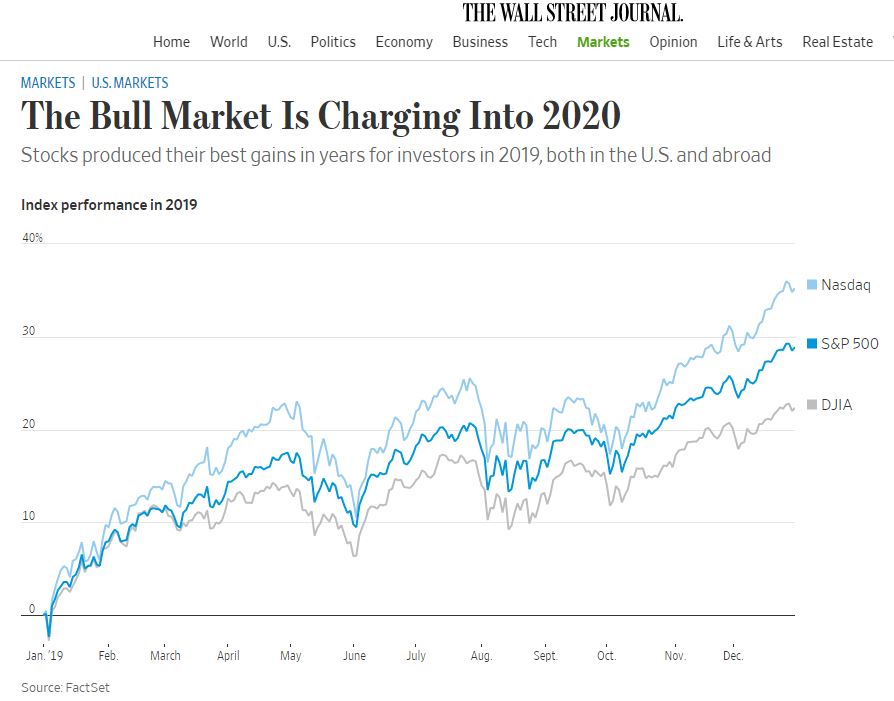

As we’ve pointed out in past Market Observers, this did not make sense to us. Equity prices rallied and credit spreads tightened in the year, reflecting widespread investor ebullience at good economic times ahead and this looks like it might just continue. The Wall Street Journal article below at the market close on December 31, 2019 says it all!

“Stocks around the world closed out one of their best years over the past decade, defying money managers who began 2019 expecting threats from the U.S.-China trade fight to slow growth or upend the bull market… For the year, the Nasdaq rose 35%, the S&P gained 29%, and the Dow ended 22% higher.”

The Bull Market Is Charging Into 2020; by Akane Otani; WSJ.com; Dec 31, 2019.

The Nasdaq up 35%, the S&P up 29% and the Dow up 22%?? That is pretty spectacular for the markets that investors had effectively written off for 2019 and perhaps forever at the start of the year. As the WSJ tells it in their article, investors were obsessed with the prospect of disinflation, deflation, Recession and even Depression:

“Just 12 months ago, the mood was far dimmer. The global economy was weakening; stocks, bonds and commodities were falling in tandem; and money managers worried the Federal Reserve’s interest-rate increases would turn an economic slowdown into a protracted downturn.”

Bull Markets usually climb a “Wall of Worry” and surprise investors who succumb to worry mode and refuse to join the fray. This one was no different, despite all the expensive technology available to investors. As we’ve told you many times in the past, investors are not just prone to psychological biases, they are literally drugged by their own body chemicals into states of euphoric risk taking, as was the case in 2019, or depression at the midst of a Bear Market. For our new readers, we are talking about the work of Cambridge University Professor, John Coates, into the human physiology of market greed and fear.

The Worst of Times to the Best of Times

It is always interesting to know where you’re coming from so we looked back at our very own January 2019 Market Observer. The markets were despondent. The Fed had been normalizing interest rates after taking them down to zero in 2009 in the aftermath of the Credit Crisis and Great Recession. This was anything but drastic, as far as the Fed tightening of monetary policies go. The Fed had only raised its Fed Funds nine times by .25%, to 2.25%.

Nobody was bullish and things seemed grim. Our January 2019 theme was Charles Dickens “It was the Best of Times, it was the Worst of Times”, explaining the investment year of 2018. The equity markets had reached record levels in September 2018, only to close down by the end of the year. Stocks fell 9% in December 2018 and it was the worst December on record since the grim Depression year of 1931!

So only a year ago, investors were in the grip of a very negative investor psychology and physiology. Now the markets have soared to new highs and there seems to be not a worry on the horizon for investors. What changed?

Soaring on Testosterone Wings

Markets soaring from the abyss are not uncommon. As panicked sellers hit bids, prices gap lower as buyers step out of the way. Once things bounce off the despair of the bottom, prices tend to rally powerfully. The forced sellers are gone and other potential sellers wait for higher prices so illiquidity leads to prices gapping upwards. This strong upwards move brings in buyers who are looking for upside.

As Coates found through his research, the financial success sends testosterone flooding through the bodies of investors. Caution is thrown to the winds and investors adopt increasingly risky behaviours. Anyone who has been involved in the financial markets for a number of years has seen colleagues succumb to reckless behaviours when they are making large amounts of money. Outsized financial success creates a feeling of invulnerability and increasingly riskier bets are made which pushes the markets higher and higher.

Avoiding a Trump Train Wreck

The catalyst for the “Feel Good” markets was the decision of the Fed to cut interest rates. There really wasn’t any legitimate justification for this, perhaps only a vague feeling that the markets needed some more “animal spirits” or a hope that a little interest rate reduction would get President Trump off the Fed’s back.

The Tweeter in Chief had been bad-mouthing the Fed at every turn at the end of 2018 and it was clear things were not great in the markets. President Trump’s understanding of economics seems to be limited to “a rising stock market means a good economy” and Trump desperately wants a rising stock market to get re-elected. Perhaps Jerome Powell and his colleagues wanted to get out of the way of the Trump Train prior to the election year of 2020.

The Fed obviously couldn’t admit to giving in to political pressure but it lowered rates three times by .25% starting July 2019. The market reacted well in advance of the actual move, with Trump’s rhetoric convincing people that Powell would cave under the pressure.

To Debt Will We Part

To us, the interesting lesson in all this is that the massive amount of debt created by the artificially low interest rate policy of world central banks cannot take even a small increase in interest rates in stride. Raising Fed Funds from 0% to 2.25% caused mayhem in the financial markets and forced Powell and company to quickly backtrack and offer some “rate cut insurance”.

The response of both the stock and bond markets to Powell’s lowering of rates was also impressive. A decrease of the Fed Funds rate by .75% moved the markets from despair in January 2019 to euphoria by January 2020. It wasn’t so much the lessening of the actual interest rate burden for businesses and consumers that improved things; it was the message that the downside of “normalizing” interest rates was too painful for the Fed. It would be economic growth at any cost going forward, even if inflation targets were busted along the way.

We pointed out in our Market Observer of January 2019 that the market had shifted sentiment and bond yields were discounting further rate increases by the Fed. The 10-year T-Bond yield had peaked at 3.2% in November 2018 and had fallen to 2.7% by January 2019. The market at that time impounded no further interest rate increases and nobody at the time was forecasting that yields would drop. Which they did with a vengeance! The 10-year yield fell in August 2019 to a low of 1.5% and the 30-year T-Bond dropped below 2% for the first time in its history. All this happened with inflation staying around the Fed target of 2%.

Inflation Denial

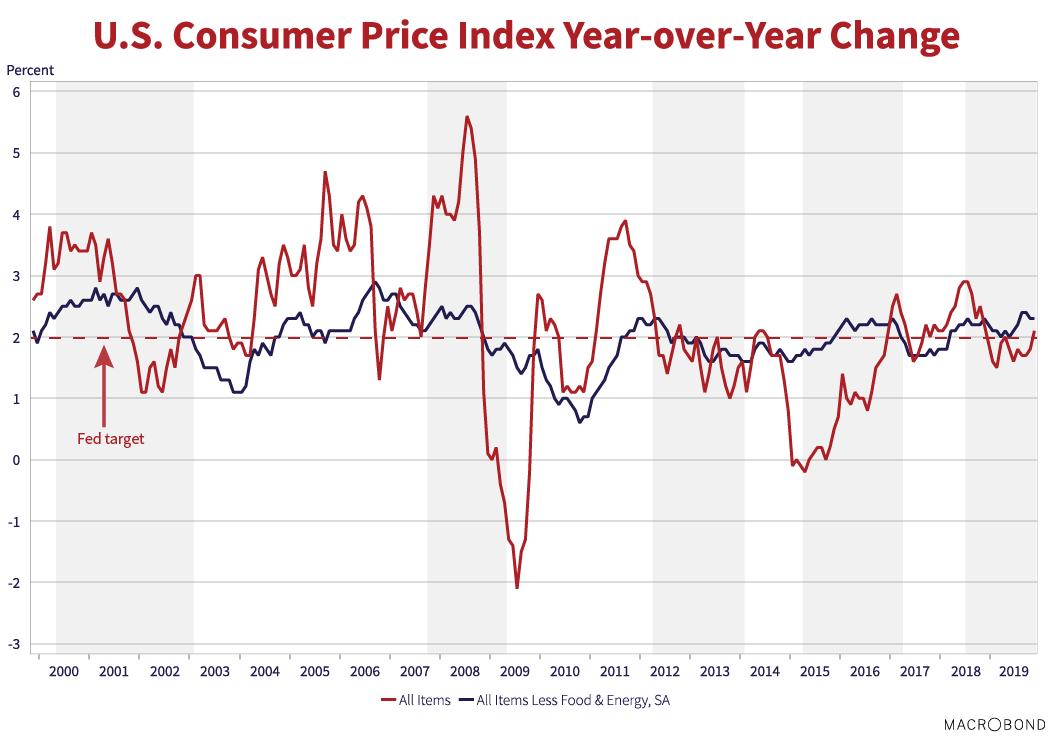

Investors are certainly not impounding a significant drop in inflation. As the chart below shows, the US CPI was 2.2% in November 2018 and was 2.1% for the last reading in November 2019. The Core CPI (All Items less Food and Energy) was even higher. It was 2.2% in November 2018 and had crept up to 2.3% by November 2019.

Investors are now willingly accepting a yield on their bonds well less than prevailing inflation. The 10-Year T-Bond yield currently is 1.8%, .3% lower than November’s 2.1% inflation reading.

The Tale of Two Markets

So bond investors are expecting severe economic weakness while stock investors and the credit markets see continuing economic expansion. This doesn’t make a lot of sense to us and we think that, as we’ve said in our recent newsletters, only one side of this argument will be right and it seems to us that the stock market and credit spreads will win the argument.

Pushy Policies

There are powerful policy forces on the side of continued economic expansion. We find it hard to believe that the current very loose monetary policy and very loose fiscal policy in the U.S. are going to change any time soon. Given that the Fed gave in to President Trump’s Twitter Tizzies and reversed course on interest rates, we think that monetary policy is on hold, at least for the 2020 election year, no matter what happens to inflation.

Fiscal policy will likely remain loose as well. As we’ve pointed out many times, the Trump Republicans have given up their conservative financial policies in favour of massive tax cuts and higher government spending, which have resulted in unprecedented peacetime budget deficits. The small government and financially conservative Tea Party faction of the Republican Party, which was created in large part to promote conservative financial policies, is fully behind the Trump Administration’s “Blow Out” budgets. It won’t be any better if the “Dems” win. No matter whom the Democrats nominate for their Presidential candidate, if he or she actually beats Mr. Trump, they have all promised higher spending and deficits as well.

Hey, Big Spenders!

This is just not an American phenomena, deficit spending is back in fashion politically all over the world. China certainly has no reticence to use its economic and financial levers to obtain its social and political goals. Even in the developed Western democracies there are not many “Small C” Conservatives left anymore as populism and its economic and political expediency takes hold.

Across the political spectrum, from the Conservative Party’s Boris Johnson’s spending programs in the U.K. to the Canadian Liberal Party and Justin Trudeau’s promised deficits, government spending is increasingly seen as the answer to the economic stagnation that is causing social and political unrest.

We were struck at how forlorn the blaring “BIGGEST SPENDERS” National Post cover on the Trudeau Liberal’s spending seemed in this age of fiscal excess. The right leaning Post wanted to highlight Trudeau’s spending ways. Far from enraging voters, it could be a positive and effective campaign Trudeau poster for the next election.

As we pointed out in our last Market Observer, Trudeau ran in 2015 on a platform of higher deficits and continued this policy promise in the 2019 Canadian election. The typical balanced budget promises were gone from his Conservative opponent Andrew Sheer’s campaign. Sheer lost the election and has since resigned as leader. Clearly, “The Thrill is Gone” from balanced budgets and fiscal conservatism as populist politicians like Donald Trump look for re-election.

Grim Hopes and Dreams

All this favourable monetary and fiscal policy and economic excitement didn’t seem to make it through to the government bond market. Contrary to the excitement at economic expansion in the stock and credit markets, government bond yields fell on the year to levels indicating severe recession or even depression. The U.S. 30-Year T-Bond yield plunged through 2% for the first time in its history in late August, hitting a low of 1.92%. We have made the point in our last couple of Market Observers that bond investors, cheered by the Fed’s “mid course correction”, were well ahead of themselves with their grim hopes and dreams of Depression.

Yield to the Curve

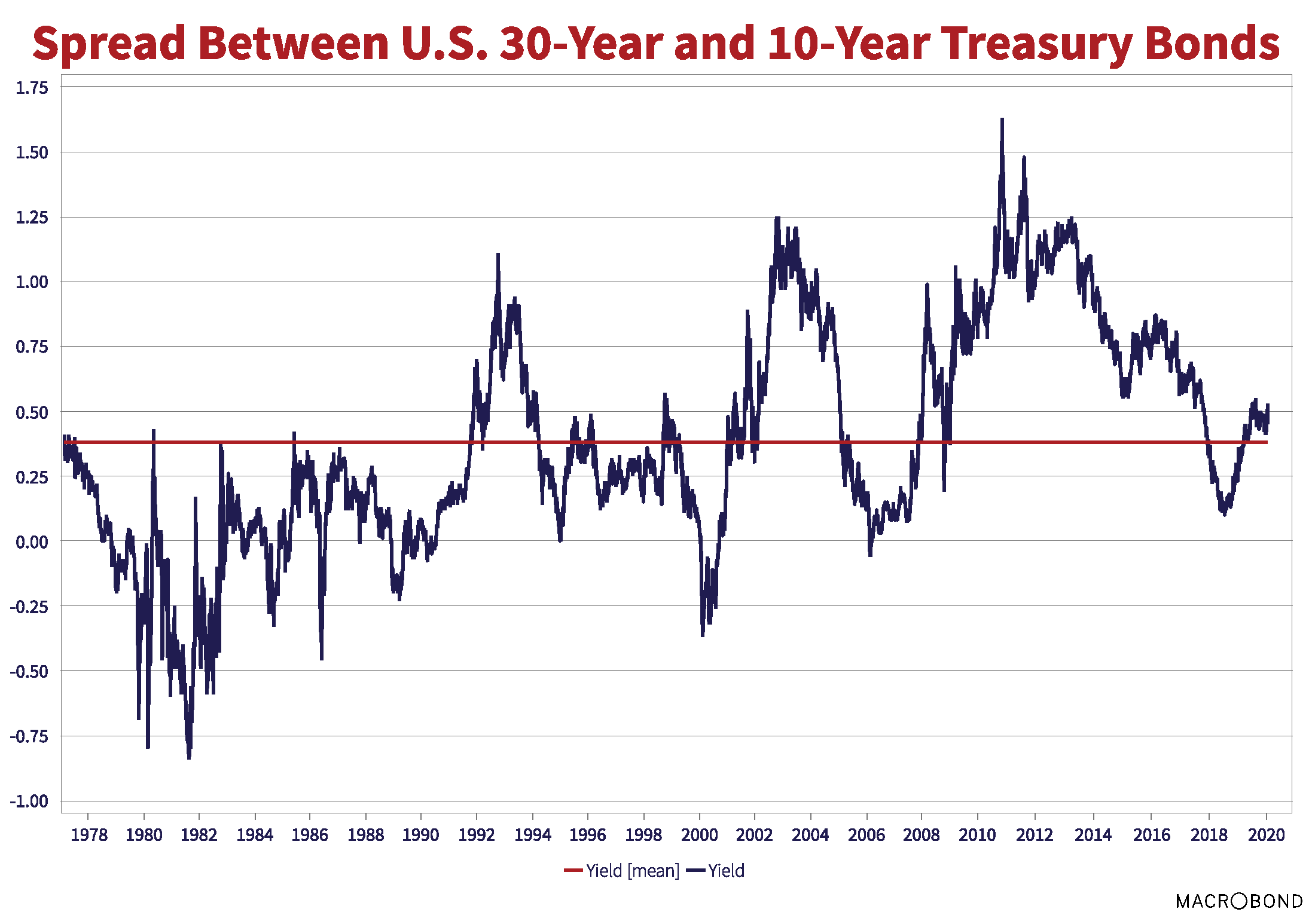

As you’ve heard above, inflation is definitely not falling in the U.S. and the economic weakness that the bond market was counting on has not materialized. The bond market now seems to be waking up to the error of its ways. The chart above shows the spread between the 10-year U.S. T-Bond and the 30-year U.S. T-Bond (30-year yield – 10-year yields) since the 30-Year T-Bond was first issued in 1978. This spread is the additional interest rate that bond investors demand to extend their term by 20 years. This makes sense, as inflation is a greater threat the longer a bond is held. As you can see from the chart, the spread has averaged .4% since 1978.

The Yield World is Not Flat

You might remember the emphasis that many bond market commentators put on the “flat yield curve” to make the argument that recession and deflation were imminent. You can see the flattening of the yield curve in the collapsing spread from above 1% from 2011 to 2014 period to .1% in 2018 as the Fed tightened monetary policy. Short bond yields rose more than longer-term yields, leading to the flatter yield curve.

Now, however, we are almost back to the average .4%. This suggests to us that investor confidence in the Fed’s commitment to low inflation has fallen dramatically. Since there is virtually no elected politician who believes in low inflation, we expect the Fed will only tighten monetary policy if inflation persists at a much higher level.

Inflation Justification

Indeed, the Fed’s staff economists seem to be busy preparing the groundwork for a period of much higher inflation. They have published academic studies that suggest periods with inflation well below the Fed 2% target should be followed by periods of inflation allowed well above target. This means we could have a protracted period of inflation well above what the bond market is forecasting.

Flagging the Lagging

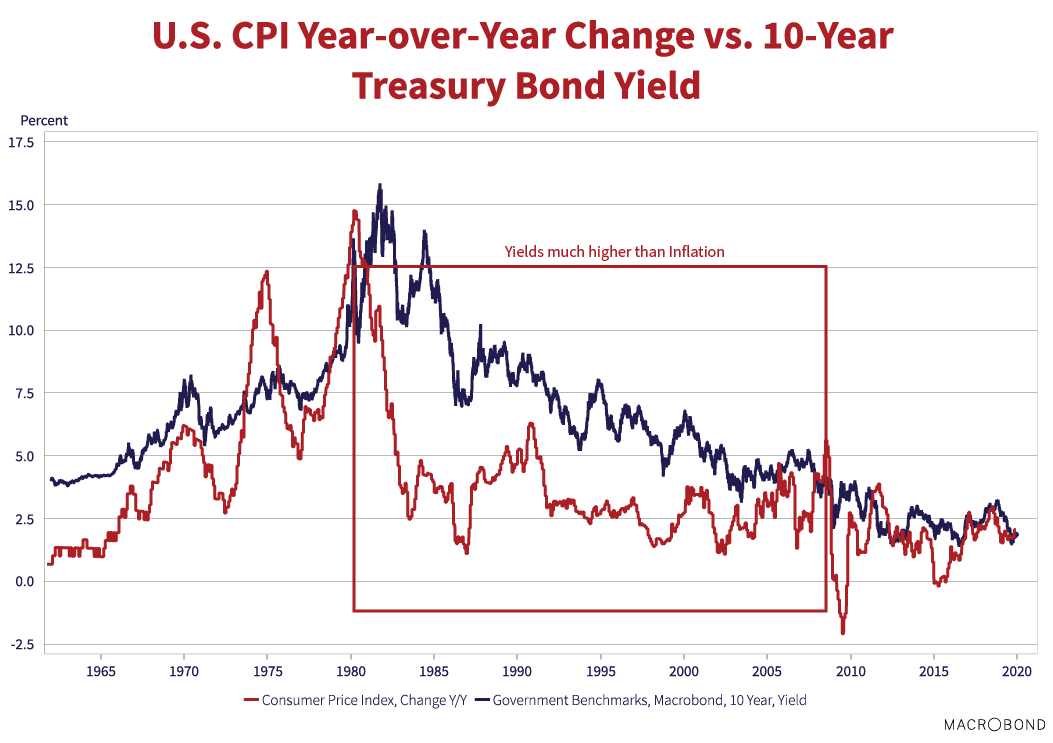

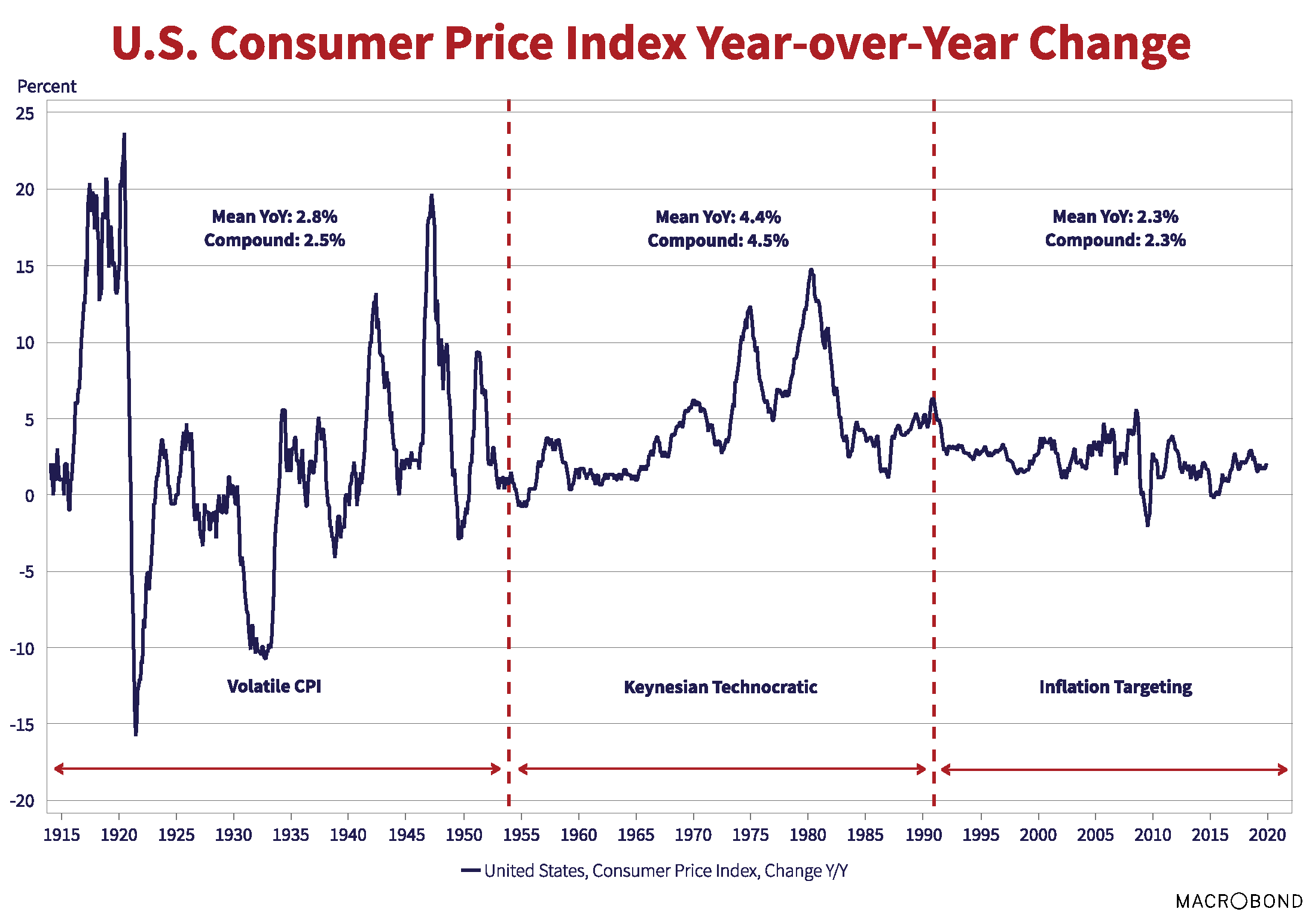

If inflation continues on its gentle upwards path, we expect that the market inflation estimate will continue to lag actual inflation, much like what happened in the 1960s and 1970s. The chart below shows the year-over-year change in the U.S. Consumer Price Index since the 1960s. Note that the period from 1960 to 1965 was a period of relative price stability with inflation between 1-2%. The Great Depression and the deflation of the 1930s were still fresh in investors’ minds in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Waiting for the Drop

By the late 1960s, inflation was picking up and peaked in 1970 at above 5%. Investors were sure that the increased inflation they were experiencing was temporary, based on their historical experience. They were quite willing to buy bonds at yields not much over prevailing inflation, certain that inflation would eventually drop. Quite the opposite happened as higher inflation became ingrained into the economy with a very substantial lobby in its favour. By the end of the 1970s, persistent and very high inflation had benefitted fixed rate borrowers as rising incomes and asset prices enriched them at the expense of lenders.

Note that the 1965 buyer of a 10-Year T-Bond in January 1965 got a yield of 4.2% when the CPI was 1.2%, for a “real yield” of 3% above inflation. That compares to the present day -.4% on a 10-Year T-Bond! Inflation then proceeded to climb and the CPI exceeded 4.2% by 1970, higher than the yield at the time of the 1965 T-Bond purchase. T-Bond yields had climbed as well, giving capital losses to the bondholder.

Advantage Inflation

What do we make of the current situation, when bondholders are falling over themselves to buy bonds with no advantage over inflation whatsoever? You can’t really blame the bondholders, since this has been the right thing to do. Yields have fallen since 1981 and reached all time lows this past summer for the 30-year T-Bond. Bond managers who prematurely predicted an end to falling yields severely underperformed and ended up being fired or retired. Their peers learned the lesson that going short your duration target was a ticket to performance and career oblivion.

Revenge of the Inflation Nerds?

What is fascinating now is the exquisite set up for a return of inflation. No one seems to be worried about inflation at the central banks, except that it is too low. Market pundits and even President Trump believe that extraordinarily low interest rates are the birthright of bond investors. Anyone who worries about inflation is definitely an “investment nerd”.

Inspection of the graph above shows that the recent path of inflation has been upwards. The CPI had peaked at just above 5% during the expansion that ended in 2008 with the Credit Crisis and Great Recession. It then fell sharply into actual price deflation at -2.4%. It recovered back above 2% by 2012 and then fell back to 0% by 2015. Since then it has been rising and now sits once again above 2%, higher than the current 10–Year T-Bond yield of 1.8%.

Slow on the Upside and Downside

One thing to note about this chart is the slow reaction of bond investors to the persistent inflation of the late 1960s and 1970s. Inflation spent a lot of time higher than bond yields, as investors waited for it to fall back to “normal” levels. In the late 1970s, inflation persisted higher than bond yields until finally the Volcker Fed severely tightened monetary policy and then interest rates and bond yields finally soared above prevailing inflation.

The extreme monetary policy worked, as inflation then plummeted from 15% to 2.5%. One salient feature of this graph is how much higher bond yields stayed above inflation. In 1984, bond yields rose above 13% when inflation only increased to 5%. Bond investors had learned their lesson that inflation was a clear and present danger and demanded yields well above inflation until the early 2000s.

This yield advantage over inflation shrank over time and has been very low or even negative since the Credit Crisis of 2008. A new generation of bond investors has now learned a different life lesson that yields never go up. If they do, it represents a buying opportunity.

Things Just Aren’t That Bad

That brings us to the present situation with bond investors besotted with dreams of recession, depression and deflation. Bad economic and financial news is good news for bond investors, clinging to their bonds with miserly yields and paying up to lock them in for longer terms, but there hasn’t been a lot of it. This is despite all the positive evidence to the contrary with the actual economy and inflation. Things just aren’t that bad.

The enduring refrain of central bankers and bond investors is that despite the good news of the moment, things are just about to get terrible and this justifies the extraordinarily low level of interest rates and bond yields. This defies the economic evidence. Unemployment is at generational lows and anyone listening to satellite radio is deluged with advertisements for truck drivers. The WSJ did a piece on how manufacturers trying to find employees to fill their backorders are offering to pay their moving cost and pay a relocation bonus.

“Manufacturers are paying relocation costs and bonuses to move new hires across the country at a time of record-low unemployment and intense competition for skilled workers…Half a million U.S. factory jobs are unfilled, the most in nearly two decades, and the unemployment rate is hovering at a 50-year low… To entice workers to move, manufacturers are raising wages, offering signing bonuses and covering relocation costs, including for some hourly positions. They are betting that spending on higher wages and moving incentives will help them find workers to fill their backlogs of orders.”

Manufacturers Increase Perks to Get New Hires to move; by Austen Hufford; WSJ; Jan. 12, 2020.

The most unfilled jobs in two decades and unemployment at a 50-year low. Higher wages and backlogs of orders needing to be filled. That doesn’t sound too weak to us but we are not drinking the bond market deflation Kool Aid. Disaster might indeed be lurking around the economic corner but then again, things just might keep on chugging along.

Breaking Even With Inflation

So what are bond investors expecting? The best guess academically of the “market inflation estimate” or the consensus investor inflation expectation has turned out to be pretty close to the last 12 months trailing inflation. As the inflation-linked bond market has developed, we have gained another way to observe some investors’ estimate of inflation. The “Break Even” (B/E) spread is the difference in yield of a conventional bond minus the real yield of its inflation-linked equivalent. If markets are efficient, then this spread should reflect the market’s estimate of inflation.

At the time of writing in mid January 2020, the real yield of the 10-Year Treasury Inflation Protected (TIP) bond was .1% and the yield of the conventional 10-Year T-Bond was 1.9%, making a B/E spread of 1.8%. The B/E spread on the 30-Year TIP was 1.8% as well.

The 1.8% B/E spread on TIPS was less than the November year-over-year inflation of 2.1%, perhaps reflecting investor expectations that CPI will fall. So the best forecast we can come up with for inflation over the next 10 years is somewhere between 1.8% and 2.1%.

#Why Buy??

So why are investors still buying 10-Year T-Bonds at 1.7%?

The major reason is that they have to. Many investors have to buy fixed rate bonds as directed by their client Investment Policy Statements (IPS). Institutional investors like pension funds and endowment funds have a portion of their portfolios dedicated to fixed rate bonds for diversification and actuarial reasons. They don’t have the latitude to do anything else. Insurance companies also must “match” their liabilities, meaning they too must invest in fixed rate bonds. Now banks and financial institutions are required by regulation to hold a significant portion of their capital in high quality liquid bonds as well. All this means that there will always be buyers of fixed rate bonds. If the Fed forces their yields down with “Quantitative Easing”, then these buyers will still be buying.

Investors are also buying because the U.S. bond market had a stellar year in 2019 that drew more funds into bonds. Bond yields fell most of the year and when bond yields fall, bond prices move up and bond investors do very well. The ICE indices showed U.S. Treasury Bonds up 7%, Investment Grade up 14.2% and High Yield up 14.4%. This means retail investors in bond mutual funds or ETFs were pretty happy and the strong performance lured more money into them.

Hugging the Benchmarks for All They’re Worth

Bond managers do have latitude to shorten their term but this has proved, as we said above, to be a one-way ticket to performance and career oblivion since 1981. Bill Gross was the founder of PIMCO and perhaps the most famous bond manager of all time with excellent long-term performance. He shortened his portfolio term in 2010, convinced that inflation would return and bond yields would rise. When yields plummeted in 2011 in the midst of the Euro-Debt Crisis, he was forced to very publicly reverse course and left PIMCO not too long afterwards in a very messy departure. So there are not many, if any, bond managers left who don’t “hug their benchmark duration” to protect themselves from career oblivion, especially after a banner year for bonds.

Having managed bond portfolios for many years, we specialize in credit and corporate bonds because we know how hard it is to forecast the economy, inflation and bond yields. For the most part, our clients specify their duration so we can focus on security selection.

For the portfolios where we do take a view on interest rates, we are quite short in term and duration for all the reasons we’ve given above. We have considerable Assets Under Management in our floating rate portfolios, where interest rates fluctuate with prevailing market rates. Given that there is a modest increase in yield and major increase in risk with buying fixed rate bonds, we think floating rate bonds are attractive and still look cheap on a historical basis.

The Mystery of Inflation History

Will things ever change? They could and bond investors ignored inflation to their peril in the late 1960s and 1970s. After their portfolios had been ravaged by rising yields they, and most importantly their clients, realized that they needed inflation protection. That’s why we thought some education on the history of inflation is now in order. To take the mystery out of inflation history, we’ve prepared the chart below of historical inflation in the U.S. since 1914, so you can’t accuse us of cherry picking our data!

We’ve divided this chart into 3 periods. The first is the “Volatile CPI” period from 1914 to 1954. The second is the “Keynesian Technocratic” period from 1954 to 1991. The third is the “Inflation Targeting” period from 1991 to the present.

The Volatile Inflation Period

The first 40 year period from 1914 to 1954 fascinates people. It starts in 1914 at the start of WW1 and encompasses the roaring 1920s, the Great Depression and deflation of the 1930s, WW2 and the Korean War. There is currently a lot of talk about how “technology” now makes things different on the inflation front.

Well, there was a lot of technological change in this period as well. In 1914, people still used horses as their primary form of transport and there was no such thing as commercial aviation. Television didn’t exist and radio was in its infancy. By 1954, people were flying commercially in jet aircraft and watching colour television programs.

Note that although the mean year-over-year change in inflation was an unremarkable 2.8% from 1914 to 1954, there is good reason to call this period the “Volatile CPI” period. Indeed, volatile inflation characterized this period. It was either going up or down, there were few periods of stable inflation. Inflation soared to over 20% during WW1 and then plunged -15% with outright deflation in the early 1920s. It went back up to 5% before the outright -10% deflation of the Depression years of the 1930s.

This was actually quite normal historically, as capitalist economies followed a cycle of financial and credit boom and bust. Rising asset values caused a credit boom that eventually collapsed on itself, with demands for loan repayment and liquidation of collateral by lenders. This caused asset prices to drop as lenders rushed to sell off their collateral, causing severe deflation during the credit bust. Once the credit cycle had reached bottom, the expansion started once again.

The Keynesian Technocratic Period

The lesson of the Great Depression was that if things got dire enough, then central banks needed to expand money supply and encourage lenders and borrowers to start up the credit cycle again. Governments also needed to spend when the private sector wouldn’t. This is when John Keynes did his groundbreaking work with his idea that low rates might not be enough to get things going again. He argued that if the private sector did not want to spend, it was up to governments to step in.

This gave rise to the second period we have identified, the “Keynesian Technocratic” period, from 1954 to 1980. Any good idea can be taken too far, and that is what happened in this period. In the mid 1950s, with the experience of the Great Depression and deflation still fresh in people’s experience, central bankers and politicians decided that they held the control levers for the economy and they would manage the economy through monetary and fiscal policy. When a downturn threatened, central bankers would lower rates and politicians would deficit finance spending programs.

Keynes prescribed low interest rates and deficit spending in recessions, which was politically very popular and attractive. Most people don’t realize that he also recommended cutting government spending and running surpluses in expansions to slow things down and repay the debt accumulated in downturns. Politicians are elected to spend, so this side of Keynes’ theory was discarded to political expediency.

In looking at this period, as we’ve shown in a previous chart, inflation was stable for most of 1960s but then began a surge upwards during the escalation of the Vietnam War and when the U.S. went off its peg to gold. Inflation soared and fell several times in the 1970s, always achieving higher levels. Persistent inflation meant that fixed rate bonds became known as “Certificates of Confiscation”. Consumers and corporations soon learned to borrow and have their debt burdens quickly reduced by rising incomes, resulting in a massive shift in wealth from lenders to borrowers. By 1980, the conventional wisdom of that time held that inflation and interest rates would always be increasing.

As we already discussed, this changed very quickly when the Volcker Fed tightened monetary policy and sent interest rates soaring to unheard of levels. Inflation peaked at 15% in 1980 and then plunged to 2.5% in 1981. As we’ve noted in the chart, prevailing inflation over the entire period was 4.4%. The thing to note was that the fight against deflation, which had been prevalent in the 1914 to 1954 period, had been won. There were no instances of deflation after the late 1950s. The cost of banishing deflation was of course inflation and this proved to be its own threat to the U.S. economy.

The Inflation Targeting Period

“Monetarist” economists argued that the inflationary spiral had resulted from the evil “Keynesians” mismanaging monetary policy in their technocratic and interventionist zeal. Volcker was not a monetarist but his conquest of inflation proved a point for them. Tight monetary policy can stop inflation cold. This gave rise to crowing from the Monetarists led by Milton Friedman who argued that the policy interventions by central banks had really been the problem. The most extreme voices argued for a set growth rate of money supply and no interventions whatsoever.

Volcker’s successor as Fed Chair, Alan Greenspan, was a very political pragmatist from Wall Street who saw his role as saviour of the markets. He famously said that it was not his job to stop financial bubbles from occurring, it was his job to clean them up after the fact. His pragmatism extended to inflation. Price stability had been considered to be the level of inflation that did not affect economic decisions and Greenspan agreed.

The 1990s saw the world’s central banks adopt “Inflation Targeting” regimes as a response to the high inflation 1970s. The first and most famous instance happened in New Zealand, which had been plagued with high inflation for many years. Keeping an inflation target of 2% became the only goal for the Reserve Bank of New Zealand by constitutional authority. This solved the inflation problem and the idea of inflation targeting caught on with other central banks. In his autobiography, Paul Volcker lamented the adoption of a 2% goal by the Federal Reserve. He believed that inflation targeting was in large part due to the “super salesmanship” and inflation-target proselytizing of Donald Brash, the then Governor of the RBNZ.

The inflation targeting regimes have actually been quite successful in containing inflation. The average year-over year U.S. CPI for the 30-Year period from 1990 to 2020 has been 2.3% and its compound growth comes in at the same 2.3%.

Command and Control Populism

So you are asking, what will happen to inflation in the years ahead? We believe that the period ahead could be what we call “Command and Control Populism”. The exultation of the financial class at the lack of inflation has led central bankers, policy makers and politicians into believing they can basically do anything they want, as President Trump bears witness to. Trump wants “zero interest rates” because Obama had them. The lack of push back from financial conservatives in the Republican Party is nothing short of amazing to us. The same politicians who fought against bailing out financial institutions during the Credit Crisis and fought the deficit spending programs in the Great Recession are happily ignoring the huge Trump deficits and his attacks on the Fed.

It now seems like low interest rates are natural but it wasn’t so long ago in 2010 that the consensus was firmly on the side of rising inflation and interest rates. That’s when Bill Gross shortened his portfolios. We did not agree, as we said at the time:

“The existing consensus has been very solidly behind rising interest rates and inflation, given the very loose monetary and fiscal policy in response to the global credit crisis of 2008. We have commented in our recent reports that we believed the consensus had inflation rising well in advance of the actual danger. The consensus flagged the unprecedented monetary stimulation and made the leap from expanding money and credit to inflation. Where we believe the consensus is wrong is the huge drag from bank capital replenishment and debt reduction.”

Canso Market Observer, June 2010.

We are still going against the consensus view. When people thought that inflation would return in 2010, we disagreed. We now believe 10 years later in 2020 that the consensus that inflation is not a problem and yields will stay low due to impending economic doom is not realistic. We think the pre-conditions are now in place for a return to higher levels of inflation than the market is currently impounding. Will it happen? Nobody knows but if it does it will certainly be a shock to bond investors.

Pushy Central Bankers

The complaints of world central bankers at the present high consumer and corporate debt levels are frankly laughable. What did they expect lowering interest rates to absurdly low levels would do? Cause less borrowing?? As we’ve said before, this is like drug pushers complaining about excess drug use.

Central bankers and politicians have been emboldened by their triumph over the Credit Crisis and Great Recession into a very interventionist stance. Gone are the glory days of monetarism and deregulation when economic conservatives held sway. Monetary policy is believed to be effective at directing the economy to whatever outcome is desired and Fiscal policy is now the plaything for populist politicians to buy their re-election.

The problem with the current political and economic construct is that it will inevitably lead to a tolerance for inflation in favour of higher economic growth. The only way out of this economic and monetary conundrum is to have increasing revenues and incomes to inflate away outstanding debt.

Bond investors are still hoping for economic or financial cataclysm to skate them onside. Since they are still expecting the worst, we point out how unusual it would be historically for inflation to be low enough to justify the present low yields. Even excluding the high inflation period, the average inflation from 1914 to 1954 was 2.8% and the average inflation from 1990 to 2020 has been 2.3%. The Fed is targeting 2% and looks ready to accept higher inflation than the market expects.

If the tolerance for inflation builds like in the late 1960s and 1970s we will be looking at something higher than 2%, perhaps something over 4%. While this seems outlandish at present, the fact nobody thinks this would be possible causes us concern. We experienced inflation in the 4-5% range in 2010 when nobody thought it could go down.

Steeped on the Tea Leaves of Policy

As we’ve said, we find it hard to believe that the Powell Fed will tighten monetary policy in 2020 and it is very unlikely that any American politician still in office will argue for shutting down the fiscal pump priming so deficit spending will continue. That means the prospect for higher interest rates in the U.S. is increasingly likely.

Since the Fed won’t be raising administered rates, we think the yield curve could steepen substantially which in itself is a potent economic portent. Trump has recently declared victory in his trade war with China, which removes another obstacle on the economy.

That means that 2020 could be a very good year for the U.S. economy. Stocks should do reasonably well but we worry about the bond market where longer-term assets are priced “for perfection”. If bond investors finally throw in the towel, yields could be up substantially for longer-term bonds.

A Harry Canada??

Canada is a tougher call, given the huge role of residential housing in our economy. While things perked up with lower mortgage rates, the Canadian housing market is hyper-extended in its valuation. We think the ownership registry for Canadian housing is necessary but, given the high level of dodgy foreign investment, it could slow things as the “offshore investors” seek a better place to hide their spoils. If housing slows with rising mortgage rates, then Canada very well could weaken economically as the U.S. continues to chug along. Higher rates of Canadian immigration helps things, but the energy sector is still struggling to rebound. Oil prices are off the bottom but, adding ethical insult to price injury, now the global ESG movement is restricting investment to the energy sector. Perhaps the rumoured relocation of Prince Harry and his family to Canada will improve consumer sentiment!

Still Watching and Waiting

In the credit markets, the “Stretch for Yield” is now in full bloom. We think the credit markets are getting expensive and despair of all the money now chasing yield in “Private Credit” and “Alternatives”. We started in the private markets and know full well how difficult it can be in a downturn. Our perusal of marketing materials shows the promoters of private debt are talking “high yields” without considering the high credit losses that investors will inevitably take. The people currently stampeding into private debt do not have any idea of the damage a turn in the credit cycle will do to their portfolios.

We find ourselves at this market juncture in much the same place as we were last year. Our closing paragraph for the Market Observer of January of 2019 was entitled “Watching and Waiting”. We did some buying in the market setback of late 2018 but since the markets have rallied massively since then, we are now once again in the “improving quality” phase of the Canso investment cycle. We are taking sales of fully valued positions and reinvesting in much higher quality and liquid securities.

We always will find some great value in our special situations, as we have recently with our Maxar bond financing, but when others have thrown caution to the winds, it is time to take profits and improve quality.

Happy New Year!