October 2015 Market Observer

Download PDFWhat’s worse, the turmoil in the markets waiting for the U.S. Federal Reserve to raise its policy interest rates or actual higher interest rates?

By delaying their heavily broadcasted intention to finally normalize their “emergency” U.S. interest rate policy, the bureaucrats of the U.S. Federal Reserve seem to have increased the angst in the financial markets. If their idea was to calm the markets, it’s not working.

The delay of the Fed was seen as positive by the bond market. Investors took the Fed’s inaction to be a sign of weak global growth and bid up bond prices that had previously been on a downtrend due to the expectation that U.S. interest rates would be increasing. After seeing falling bond prices when the Fed was expected to raise rates, the Canadian bond market recovered most of its losses to finish up a marginal .15% for the quarter. On the other hand, the Fed’s worry on global issues put paid to riskier assets. The Canadian dollar continued down with commodity prices. Equity markets experienced their worst quarter in some time in the third quarter of 2015. The resource heavy TSX was down -7.9% in the quarter and the S&P in the U.S. was down -6.4%.

A Tizzy of Rate-O-Phobia

Chair Janet Yellen and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), in their “utmost caution”, have used almost every excuse to delay and postpone the day of interest rate reckoning. This dithering seems to have been going on for years, which it has. The Fed says that it is “data dependent” but its decision criteria are very much a moving target. Their prior employment and economic “hard targets” have been blown through as new more “flexible” ones have been latched onto. If the intended result was mass confusion and market jitters, the FOMC couldn’t have done any better.

The third quarter of 2015 saw the seemingly inevitable September day of interest rate decision moved off into the fuzzy future once again. After the September FOMC meeting, Ms. Yellen explained that foreign markets and market tumult were enough to delay the inevitable. Once the market heard this message and rallied on this seemingly great news, the Fed Chair and Governors then proceeded to speechify that interest rates were indeed destined to rise by the end of 2015. This then sent the financial markets back into a tizzy of rate-o-phobia.

Pushing the Fed Around

At the time of writing in early October, a “soft” September U.S. employment report came in at 140,000 jobs instead of the consensus forecast of 200,000. Now traders are firmly convinced that the Fed will continue its dilly-dallying and delay even longer:

“Yields plunged across Treasuries maturities Friday after the Labor Department said the economy added 142,000 positions in September, short of the median forecast of 201,000 in a Bloomberg News survey. The data add to the challenges in the U.S. and abroad that confront Fed officials as they try to normalize interest rates. Investors are speculating that economic headwinds in Europe and Asia, as well as falling commodity prices, will push the Fed to hold back even longer.

‘I don’t know how anyone could see them doing anything in the face of the figures we had,’ said Thomas di Galoma, head of fixed-income rates and credit at ED&F Man Capital Markets in New York. ‘What you’re going to see here is Wall Street firms continue to push back their estimates of when the Fed is actually going to raise rates.’” Bloomberg.com: Gulf Widens Between Fed Forecasts and Signal From Futures Market Daniel Kruger, October 3, 2015

No Cost Money

As we have said in previous editions, more money will always be more popular than less money. The cheerleaders for looser monetary policy will always be more vocal than those who believe that policy should be normalized from its emergency levels. The “Leave Rates Low” faction believes that the risk of higher inflation is acceptable; indeed that higher inflation is a preferred alternative to slow economic growth. We’ve come a long way from the 1980s when the economic policy and markets orthodoxy was focused on money supply. The consensus then was that producing more money than the economy actually needed would simply create higher inflation. Of course, the markets and economy had just come through a long period of rising inflation and interest rates. Now the consensus is that no cost money at zero interest rates is the solution to all economic ills, real or imagined.

People can be excused for being confused. Investors were terrified of all the money created by the Federal Reserve in the aftermath of the Credit Crisis and they were certain that this would result in inflation in 2009-10. When runaway inflation did not appear, the gold and commodity markets mania turned to fears of deflation after the Euro Debt Crisis in 2011-12. The specter of a Japan-like deflation has hung over the markets ever since.

The manic market swings around intended Fed policy reflect the tremendous uncertainty of both policy makers and investors. We truly are in new economic and market territory and it is important to elevate one’s analysis above the short-term swings in market sentiment and economic statistics.

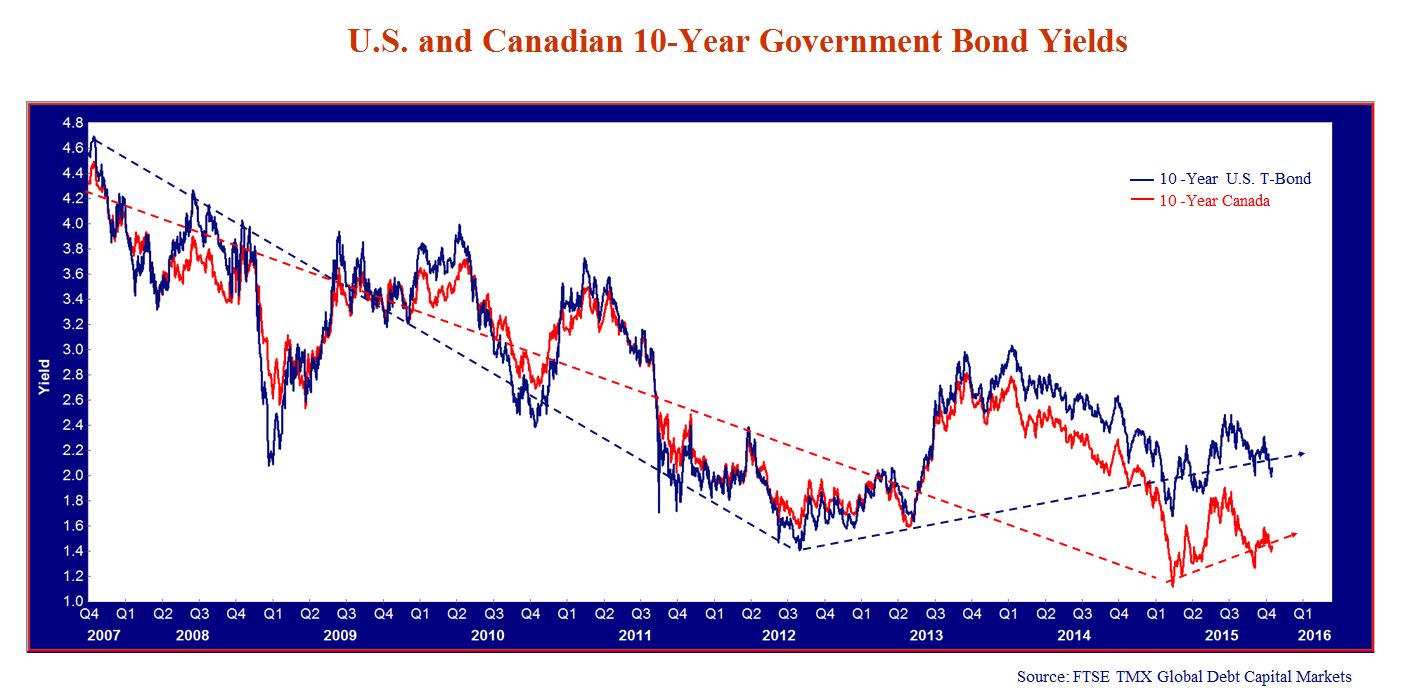

As can be seen in the chart above, the 10-year yield in both Canada and the U.S. has been in an uptrend since the sharp drop in yields during late January. The U.S. 10-year yield seems to have reached its low in 2012 during the Euro Debt Crisis. Canadian yields reached their low this January. Both seem to be in the process of gradually rising to more “normal” levels.

Don’t Worry, Be Employment Happy

Why not, you should ask if you are an American. Canadians, with the energy sector imploding, might have reason to worry but U.S. employment has been restored to pre Credit Crisis levels. The U.S. economy is growing reasonably and consumer confidence has grown along with employment. The housing market is in fair shape and car sales are very strong. The problem for the Fed is that most of the global economies outside the U.S are tanking with commodity prices and a weakening Chinese economy.

These international concerns are really outside the “dual mandates” of the Fed: controlling inflation and targeting full employment. For a Fed obsessed with not making a mistake, however, international concerns and markets now seem to play a very important role in their deliberations.

Will They or Won’t They?

Will they or won’t they? We really don’t care. Our job is to price risk and return. We can see that the yields and potential returns on bonds are both very low and that the downside price risk to longer dated bonds is very high. You have to go back to the 1930s to find bond yields this low. Indeed, with interest rates at generational lows, there are very few practicing bond managers who have seen fixed income price risk.

As most of you know, as part of our practice of investment, we at Canso study investment history. As most contemporary investment professionals think a couple of quarters is a “long-term focus”, this gives us a rather unique perspective on the current level of interest rates. Our peers, habituated to the predominately one-way drop in bond yields since 1981, think the current economic situation is disinflationary, if not deflationary. This suggests to them that our current low yields might even go lower or even turn negative. We are not so sure.

Not Since Napoleon

Yields are now lower than at almost any time in recorded financial history. Indeed, the British government is calling perpetual notes that were issued to fund the Napoleonic Wars since they can issue new bonds at lower yields:

“The UK government has announced that it will repay a small portion of ‘perpetual’ debts that date back to World War I and the South Sea Bubble. National War Bonds were sold in 1917 under the slogan “If you cannot fight, invest all you can in 5% bonds”, reports Elaine Moore. The government bonds come with no fixed maturity date but give the government the option to repay with 90 days notice. The government says it will redeem the remaining £218m of the 4% Consol, leaving about £2bn of perpetual debt remaining. The government is now looking into the practicalities of repaying the full amount.

This Consol was first issued by then Chancellor Winston Churchill in 1927, partly to refinance National War Bonds originating from the First World War. The UK’s Debt Management Office estimates that the country has paid £1.26bn in total interest on these bonds since 1927. In addition to the 4% Consol, some of the debt being repaid dates as far back as the 18th century. In 1853, then Chancellor Gladstone consolidated, among other things, the capital stock of the South Sea Company, which had collapsed in the infamous South Sea Bubble financial crisis of 1720.In 1888, Chancellor George Goschen converted bonds first issued in 1752 and used to finance the Napoleonic and Crimean Wars, the Slavery Abolition Act in 1835 and the Irish Distress Loan in 1847. This debt will be repaid through the redemption of the 4% Consols, the UK Treasury said in a statement.”

Source: Financial Times, UK to repay part of perpetual WWI loans, Fast FT by Elaine Moore, https://www.ft.com/intl/fastft/229142/uk-repay-loans-from-wwi-south-sea-bubble

We show the current yields on different 10-year government bonds in the table below.

The U.S. 10-year T-Bond yield is currently 1.99%. The 10-year Canada bond is currently lower at 1.4%, reflecting the perception that the Canadian economy is weakening due to the commodity sell off, particularly in the energy sector. The United Kingdom has a 10-year yield of 1.7%, which is why they are calling their perpetual issues with coupons of 4-5%.

Hardcore Interest Rates

The “core” European bond yields reflect the European Central Bank’s quantitative easing program with Germany at .51%, France at .89% and the Netherlands at .69%. The peripheral Euro bond yields are low as well, reflecting the successful resolution of the Euro Debt crisis. The fears that Italy, Spain and Portugal would leave the Euro zone and default are obviously now muted with their yields at 1.63%, 1.77% and 2.28% respectively. Japan, mired in deflation since the 1990s, has the lowest major economy bond yield at .31%. It is only the weak credit of Mexico, Brazil and Greece that has their yields at 3.52%, 5.58% and 7.91% respectively.

Given the low levels of global bond yields, the question is whether they will continue as in the case of Japan. We believe that Japan is a special case with its economic deflation being exacerbated by its aging demographics and cultural aversion to immigration. We again turn to history to evaluate the prospects for bond yields.

Back to the Interest Rate Future

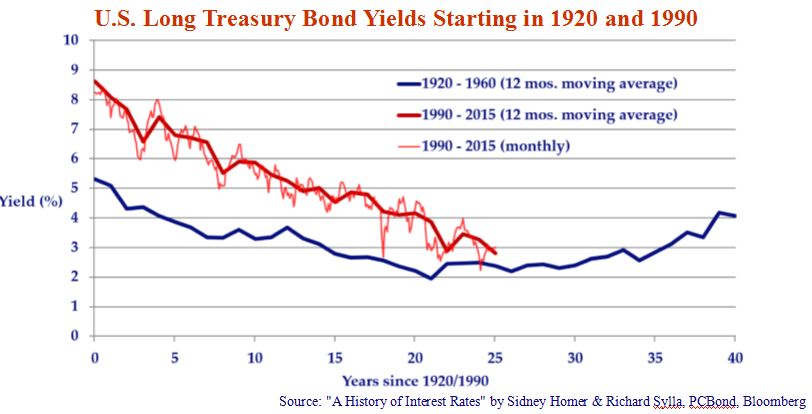

In the chart below, we have updated our chart of the long-term U.S. Treasury Bond yield from 1920 to 1960 (heavy blue line) comparing to this yield from 1990 to the present (the heavy red line). The long-term T-Bond yield is plotted versus the number of years from 1920 and 1990. For example, Year 15 is 1935 on the blue line and 2005 on the red line, fifteen years from the start dates of 1920 and 1990, respectively.

We find this chart a striking reminder that the present level of bond yields is exceptionally low in any historical context. Note that, as we have said earlier, U.S. yields did not turn negative in the deflationary 1930s when consumer prices were at times falling -4% and unemployment was above 30%.

In our prior editions we went through the intuitive logic of this comparison that drew parallels between the massive productive capacity that was unleashed by both the ends of the First World War and the Cold War. As our loyal readers will remember, we are firm believers in the business and credit cycle brought about by changes in productive capacity, technology and innovation. The massive industrial capacity created by the First World War was diverted to civilian production in the 1920s. In particular, the United States which entered the war late and did not sustain serious damage to its industrial base. The end of the Cold War and the Soviet Union also saw diversion of immense resources into peacetime uses in the 1990s. The entry of China as an industrial producer into the global economy was an especially potent supply side shock.

You will note that we have added an extra line in this chart. Our early 1919-1959 historical data is monthly and the heavy blue line is the 12-month moving average of these data points. For ease of comparison, we have used a 12-month moving average for the modern period since 1989. We have now added a light red line that plots the actual monthly data. This shows the current yield on the U.S. long bond is just below 3% after falling to 1930s levels of almost 2% in January of this year.

Hurt Bond Feelings

A historical context is important to anchor emotive conclusions. Yes, you “feel” things economic and financial are awful and that justifies to you that yields should stay low forever. You might debate that the current U.S. unemployment rate is understated given the low participation rate, but in no way is it as searing as the breadlines and over 30% unemployment rate of the 1930s when there was a limited social net. You might also argue about the effect of technology on inflation. The 1930s saw the advent of radio, air travel and widespread use of motorized automobiles and trucks. Concerned about the fragility of the present financial system?? The stock market crash of 1929 and the banking holiday of 1933 were far worse than our modern equivalents during the Credit Crisis and the Euro Debt Crisis.

Inspection shows that the monthly moving average is tracking the 1930s experience, albeit at 1-2% higher in yields. Our take is that, like in the 1930s, we are presently seeing the bottom in the long yield that should be flat to up in the next 5-10 years. The daily data has at times moved towards the lows of the 1930s but is on average staying well above.

The Real Deal

What does this mean for an investment portfolio? Clearly, if we are seeing yields bottom, it should mean that investments with longer terms and fixed cash flows are not as desirable as they were with falling interest rates.

On a real interest rate basis, things are very different than the 1930s. During that era, as we can see from our long Treasury chart, both fixed and floating rate nominal (before subtracting inflation) yields stayed in the 2% range. With deflation of -4% at times, the real interest rate was in the order of 5-6%. Credit spreads on corporate debt were quite high as well, ranging from 2-4%, since defaults were high. That meant a consumer or corporate borrower was paying 4-6% in nominal interest rates with deflation putting the real rate well above 6% for most borrowers.

Contrast this to the present real rate situation. LIBOR, the floating rate U.S. dollar benchmark, is not much above zero and the 10-year treasury is about 2%. Corporate credit spreads for investment grade borrowers are 1-2% above the government. This makes for a floating rate of 1-2% and 10-year fixed rate debt of 3-4%. With inflation at 1.5%, the corporate U.S. borrower is paying a zero real rate for floating rate debt and 1.5-2.5% real interest rates on fixed rate debt.

Mucho Money

The difference between today’s very low real interest rates and the much higher ones during the 1930s Depression are the very activist monetary policy by the Federal Reserve and other global central banks. High real rates reflect the scarcity of investment capital. With capital scarce, borrowers must pay a very high real interest rate to attract capital which is what happened during the Great Depression. We are currently in the exact opposite situation. There is so much money available via very loose conventional monetary policy and quantitative easing (buying of government bonds by Central Banks) that real interest rates are very low on a historical basis.

Will real interest rates increase? They will only increase if monetary policy is sufficiently tightened to make money scarcer, since real interest rates are the “price of money”. This is the great uncertainty in the financial markets at present. Nobody actually knows what will happen when the Federal Reserve “normalizes” monetary policy. Will money actually be scarcer? Not according to Janet Yellen who has told us many times that monetary policy will remain very accommodative despite a normalization of interest rates.

The experts and the financial market consensus were obviously wrong when they predicted in 2009 that higher inflation would result from the very aggressive monetary policy and quantitative easing after the Credit Crisis. Now the experts and consensus seem to be on the side of leaving interest rates at “emergency” very low levels for some time.

Are Low Interest Rates Good for the Economy?

The economist and market consensus is very much that low interest rates stimulate economic activity by encouraging borrowing. We have made the point that artificially low interest rates penalize savers, as they have much lower income than they otherwise would. The expert consensus is stumped by the “new normal” and low growth economies worldwide.

The good economists at the central banks should really go back to their economics textbooks and observe that Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the value of all goods and services produced by an economy, is theoretically equivalent to Gross Domestic Income (GDI), the value of all salary and investment income in an economy. Is it any wonder that GDP is disappointing when people are earning nothing on their savings? By definition, if interest income has dropped, this is a downwards pressure on GDI and therefore GDP.

To this point, the drop in interest income has probably been offset by an increase in realized capital gains on financial investments like bonds and stocks. If we stay at current yield levels, this will no longer occur, as investors will have to depend on the income from their investments rather than harvesting their price gains.

Low and Not Loving It

Think of what is happening here. All those dependent on financial income have seen a stupendous drop in their income due to declining interest income. Pension funds are a case in point as actuarial assumptions for investment earnings have been lowered, necessitating large contributions by sponsors to fund their obligations which reduce shareholder income. At the consumer level, people who have falling incomes are not likely to spend effusively.

In our view, the gains from expansive monetary policy encouraging borrowing are now probably less than the negative effects of lowering the income of savers. We have commented on this before but recently have seen other analysts making the connection. A recent Bloomberg article commented on this downside to low interest rates:

“Deutsche Bank posits that lower real interest rates reduce a households’ expected return, thereby prompting them to save more in order to meet their long-term financial goals and forego spending today.

The team estimates that Fed policy has driven real rates in the U.S. to 2.5 percentage points below their neutral levels, which has resulted in a 0.9 percentage point rise in the savings rate. Any increase in the savings rate entails an offsetting decrease in the consumption rate, as households refrain from spending that portion of their income, which weighs on current economic activity.” Bloomberg Business: A Core Tenet Of How Central Bank Stimulus Supports Growth Doesn’t Fit The Data, According to Deutsche Bank; Lower rates actually hurt consumers. Luke Kawa, October 5, 2015

A Risky Return

We know that any forecast will be wrong. All we can really say is the additional potential return for accepting interest rate risk (the chance that interest rates might rise) is also very low at present. A 5-year U.S. T-Bond currently has a yield of 1.3%, the 10-year 1.99% and the 30-year 2.83%. This means an investor earns an extra .69% (1.99-1.3) for extending term from 5 to 10 years and an extra 1.53% (2.83-1.3) for going to 30 years. The downside risk for a 5-year T-bond is a drop of 4% for every 1% rise in yield. For the same 1% increase a 10-year T-Bond would drop 7% in price and the 30-year would drop 15% in price.

To us, the additional yield of 1.5% to extend term from 5 years to 30 years does not adequately compensate for the downside price risk. Of course, the opposite is true. What goes down could go up. If yields drop 1%, then a 30-year T-Bond would be up in price by 15%, which is why bonds have done so well in a declining interest rate environment.

The absolute low level of bond yields changes this calculus somewhat. Starting from the current 2.9% for a 30-year T-Bond, a 1% drop would put the yield at 1.9%, about the same level as the current Fed inflation target providing a 0% real yield after inflation. Even if inflation ended up staying at 1%, a real yield of .9% doesn’t provide much compensation for a bond investor.

Only In Canada…

Canadian yields are starting from an even lower base. The 5-year Canada yield is now at .77%, the 10-year at 1.39% and the 30-year at 2.19%. Current Canadian inflation is 1.3% year-over-year. The Bank of Canada has an inflation target of 2% and has managed to achieve this on average since it started inflation targeting in the 24 years since 1991. What all this means is that inflation in both the U.S. and Canada will have to be at a very low level to make the risk return trade off attractive for bonds at the current yield level. This is not to say that a truly deflationary scenario is improbable. We are certainly seeing this in commodities after the end of what we called the Commodity Mania.

Given the reasonable U.S. economy thus far, we do not think that deflation is likely in the U.S., although a rising U.S. dollar has dampened inflation pressures. If indeed the Fed does normalize interest rates and the U.S dollar continues to rise, it would put inflationary pressures on other countries with weaker currencies.

An Unhealthy Fixation

Canada would be particularly exposed to rising yields, as the Bank of Canada seems fixated on weakening the Canadian dollar to compensate for the resource bust. This is a risky proposition, as a sharply depreciating currency risks a free fall as citizens rush to protect their purchasing power. Canadians are already experiencing import price inflation, particularly in groceries, which has been masked to some extent by falling energy prices. While the Bank of Canada currently is a big fan of a weaker Canadian dollar, this would change if confidence craters. This is definitely not the case at present with Canadian bond yields lower than American. This could change rather quickly. In previous episodes of declining commodity prices, Canadian yields were significantly higher than U.S., which means Canadian yields could rise more than those in the U.S.

The Financial World Will Not End

What’s a poor bond investor to do? Well, the financial world will not end if and when the Fed normalizes interest rates. Our rather exciting view is that all the worry normalizing interest rates is NORMAL. Remember the worry about the end of “Quantitative Ease”? The financial experts were predicting doom that didn’t transpire as the U.S economy continued its improvement. If we are not going into deflation and Depression, it looks to us that we are seeing a very protracted bottoming of bond yields. Bond yields and prices will bounce around but we think the risk of rising yields to our portfolios is a greater risk than the risk of missing a bond market rally.

We think it is better to accept credit risk to earn extra yield than to extend term. It will be very important, given tightening credit conditions, to do your credit work. We like floating rate securities that have attractive yields compared to the fixed rate alternatives. The recent widening in credit spreads is making long-term corporate bonds potentially defensive for longer duration portfolios, if and when yields finally do rise.

The market and investors always crave certainty but never get it. Things go up and down and will continue to do so. Will the Fed raise interest rates before the end of 2015? Not even Janet Yellen and the Fed will know until they’ve made their decision. All we can do is price risk and position our portfolios appropriately.

2023

2022

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

2015

2014

2013

2012

2011

2007

2006