THE CANADIAN HOUSING MARKET

Imagine two cars in a race. One is the Canadian housing market and the other is the American housing market.

The Canadian racing team is continually losing to the American. The Americans have developed a new type of engine, called “securitization”, which has allowed them to reach much higher speeds than the Canadians. The securitization engine uses a fuel called GSE that can only be found in the United States.

The Canadians study the American design and come up with their own version of the securitization engine. Since the Canadian teams cannot use the GSE fuel, they develop their own variety called CMHC. They do this by modifying an existing lower octane fuel called BHA (Boring Housing Agency) and turn it into a much higher octane fuel using the “bulk portfolio insurance” process which uses additives like longer amortization and 100% financing.

The new Canadian securitization engine is very good. For the first time in many years the Canadians can keep up with the Americans and even pull slightly ahead of them. Both cars race faster and faster. The Americans notice their engine is overheating. The Canadians notice the same thing.

The Americans are worried about blowing their engine. They slow down. The Canadians pull farther ahead. The Americans talk it over and are unwilling to risk completely burning out their engine so they direct their driver to pull into the pits for a look. Once they lift the hood, they realize that the problem is the GSE fuel. Their car is running so hot it risks an explosion. They drop out of the race and the Canadians win.

People are shocked that the leading American team has lost and racing commentators marvel at the Canadian design. The Canadian team is lauded for the genius of their design and the Canadian team members become famous. They like it.

The Americans decide to change their securitization engine and run with a lower octane fuel. The Canadians stick with the CMHC fuel, although it runs very hot, and even add a secret ingredient called IMPP. This makes the Canadian car run even faster. The problem is that the risk of explosion with the Canadian securitization engine is now even higher.

The Canadians see that their engine is running hot, but they ignore it. For the first time in many years, they are far ahead of the Americans and winning races. They like the feeling of winning and get glowing international media exposure. The speed of the Canadian car increases and the racing world marvels. No one listens to the few Canadian team members worried about the risk of explosion. They believe the safety of the car and driver are being sacrificed for fame and fortune. Winning races has become everything.

Car racing aside, there are many conflicting opinions on the Canadian housing market. This is not unusual at a turning point. We have been talking about what we term the Canadian “insured mortgage mania” in our newsletters since 2009. Other analysts are now questioning the health of the Canadian housing market. These include Capital Economics, The Economic Analyst/ Ben Rabidoux and now the venerable Bank Credit Analyst of Montreal. The Bank of Canada has also remarked on the speculation in the Canadian condo market and “Official Ottawa” is unofficially very, very nervous.

International economic commentators such as the Economist magazine and the OECD have analyzed Canadian housing and found it very expensive by both world and historical standards. Economist and Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman weighed in recently during a visit to Toronto:

“Mr. Krugman explains most economists initially considered the 2009 recession to be the simple byproduct of the financial crisis (which it has turned out not to be)…“As a result, many economists — myself (Krugman) included — turned to a view that stressed nonbanking issues, especially the broader effects of the collapsed housing and the overhang of private debt.” That’s where Canada functions as a potential case study. Our household debt and home prices keep trending to unnervingly higher levels.”

Most Canadian bank economists refuse to even contemplate a negative housing scenario. It could be that they can’t accept that their employers would be under pressure and not able to pay their bonuses. It could also be that they have maxed out their staff mortgages and spent their bonuses on very expensive houses. Robert Kavcic of BMO Capital Markets recently argued that those calling the Canadian housing market a “bubble” exaggerate the situation.

TD Bank economist Diana Petramala defended Canada against the scourge of prescient economic analysis by Mr. Krugman. Widely quoted in the media, Ms. Petramala pointed out that ultimately the ability of borrowers to service their mortgage payments is what is in question. Ms. Petramala thinks Canadians can service their debts despite their houses being very expensive relative to their incomes. If you accept that Canadians will always be able to service their debts in any economic and interest rate environment, then you must agree with Ms. Petramala.

Housing Confusion Around the Globe

Canadians are finding it hard to get a clear picture of where the housing market is headed, with all the conflicting “expert opinion”. Readers of the Globe and Mail can be excused for being confused. On July 1st they read a headline that stated: “Canadian housing market defies doomsayers with spring surge”. The “Don’t Worry Be Happy” contingent were out in force:

“Then we’ve had an inflection point, and went into a moderate positive trend since the beginning of 2013,” said Mathieu Laberge, deputy chief economist at CMHC… which would be the “softlanding” policy makers want and a long way from dire predictions of a 10-per-cent to 25-percent price crash…“I’d say we feel good. I mean, we’re not out of the woods yet, but we feel good,” said Brian Hurley, chief executive officer of Genworth Canada, a unit of Genworth MI Canada Inc. and the largest private residential mortgage insurer in Canada.”

Both real estate experts quoted, Mr. Laberge of CMHC and Mr. Hurley of Genworth MI Canada, work for mortgage insurers that insure 75% of all Canadian mortgages. This might slightly colour their opinion on housing matters. Mr. Hurley, despite his bravado on investor conference calls last year, now admits to “feeling afraid last year when sales dropped and analysts worried that tighter mortgage rules had squeezed too many buyers out of the market.”

A couple of days later, Globe readers were treated to a not so positive headline that read: “Toronto’s soaring condo market ignites fears of a U.S.-style crash”. Ian Austin of the New York Times Service quoted CIBC Economist Benjamin Tal: “There is no question that the housing market in Canada is overshooting… Now the cocktail party conversation in Canada is: ‘Will this lead to a U.S.-style crash?” Mr. Tal, who probably didn’t realize his quote would appear in a Canadian newspaper, went on to explain how Canada escaped the global recession: “In Canada during the recovery it was almost a crime not to take a mortgage… We were able to borrow our way out of this recession, which is why we are now sitting on this elevated debt level.”

Two days later, the Globe was back to another positive headline: “Greater Vancouver housing market shows signs of revival” reflecting MLS sales up 11.9% year-over-year in June. This was off a very low base last year and all was not rosy as sales were 22% below the 10-year average for June and down 8.3% from May. What is really interesting is that the title of this article seems to have been changed from the original “Vancouver real estate sees more sales and softer prices” as Google carried another earlier version with the more negative title. As we say, the real estate spin machine demands positives!

Canadians Have Been Borrowing at Unprecedented Levels

What is clear is that Canadians have been borrowing at unprecedented levels since mortgage credit became so easily available. What is also clear is that Canadian housing is some of the most expensive in the world on a variety of measures.

In investments, we have found that intuition is indispensable as a tool when combined with good analysis. Our gut feeling on the Canadian housing market is that it is a speculative and frothy mess that is about to come crashing down. We decided that a more in-depth analysis would be useful confirmation for our own investment purposes and to alert our clients and friends to the high risks we see going forward.

So what is so wrong with borrowing to the maximum possible for a house, given that interest rates are so low? We see many issues with this behaviour:

- Interest rates could eventually rise and cause consumer stress;

- The principal amount of a loan comes due at some point;

- Monster homes and empty condos are not great for Canadian productivity;

- The inevitable reversal of the residential boom will be felt economically;

- A decline in housing equity will reduce borrowing and consumption;

- The banking system will be strained as mortgage defaults rise;

- Government finances will be strained by falling tax revenues; and

- The huge mortgage insurance liability could threaten Federal government solvency.

Canadians Cannot Afford Their Houses

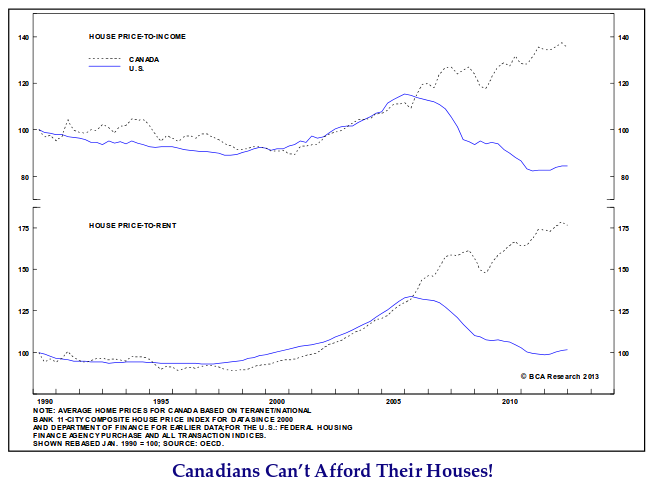

It is now becoming clear just how much Canadians have borrowed. As we said earlier, the stalwart analysts at the Bank Credit Analyst turned their analytical gaze towards the Canadian housing market in their May 2013 edition (Vol. 64- No. 11). Since we are a subscriber, we asked for permission to use some of their charts and Canadian and U.S. House Price to Income and Rents they aren’t for the faint of heart.

The BCA shows that Canadian and U.S. house prices tracked very closely as a multiple of income from 1990 to 2007. The chart above indexes the ratio of house price to income to 100 in 1990. In the decade from 1990 to 2000, both Canadian and U.S. ratio of house price to income fell from 100% to 90% of the level at the start of the decade. Then, reflecting the credit mania, they rose to above 110% at the peak in 2006. After the credit crisis, U.S. housing prices fell precipitously to 80% of the 1990 level. Canadian house prices to income rose stratospherically to nearly 140% of the 1990 level, reflecting the immense mortgage stimulus of the Insured Mortgage Purchase program (IMPP) and the supercharged mortgage lending by government backed banks.

As the BCA chart shows, prices as a multiple of rent aren’t any better. The price to rent ratio shows the affordability of housing compared to the alternative of renting. It also shows the attractiveness for investors of buying a house and renting it as an investment. From 1990 to 1999, both Canadian and U.S. houses stayed constant at their 1990 ratio level of 100. In 1999, the ratio started to climb as easy credit drove housing prices higher and the willingness of lenders to lend on property value, rather than the cash flow from rents increased. Both the U.S. and Canada increased to 130 in 2006. This was the peak for the U.S. as crashing housing values have brought the present ratio back to 100 where it started in 1990. Canada’s mortgage mania went into overdrive and drove the ratio to its present 175 in 2013. If the Americans were imprudent in their lending, we have now gone completely insane in terms of the support to prices from incomes and rents.

The Great Canadian Debt Binge

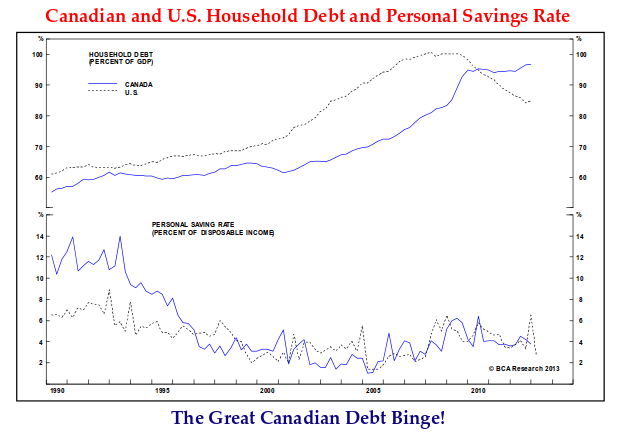

In another great chart called “The Great Canadian Debt Binge”, shown below, BCA illustrates that Canadian household debt was 55% percent of GDP in 1990, compared to 61% in the U.S., perhaps proving that at that time Canadians were more financially prudent.

We Canadians were obviously tired of playing second debt fiddle to our neighbours to the south and did something about it. The U.S. saw its ratio drop to 85% in 2013 but the Canadian ratio climbed to its present and all -time high of 97%. The consumer debt to GDP ratio is now 12% higher in Canada than in the U.S. This is the first time in recent history that prudent Canadians have out-borrowed the previously feckless American consumers.

Hugely Dependent

So what does this mean for the Canadian economy and the Canadian financial system? Well, as we have been saying for quite a while, we think Canadians will suffer from withdrawal symptoms from their insured mortgage credit dependency. The extent of the Canadian government subsidy to both the banking sector and Canadian homeowners through government guaranteed mortgage insurance is huge. This was not always the case.

The Federal government did not always make it easy for Canadians to buy their houses and subsidize their mortgages. As Jane Londerville explains:

“Until 1935, the typical loan-to-value ratio for home loans in Canada stood at 50 percent; purchasers needed to accumulate the remaining half. In that year, the Dominion Housing Act (now the National Housing Act, or NHA) allowed for joint lending of up to 80 percent of the value of a home, with 75 percent of the funds from a lender and the rest from CMHC. By the late 1940s, the typical maximum loan-to value ratio from a private lender had risen to 66 percent and the maximum NHA loan remained at 80 percent. Only with the introduction of mortgage insurance (MI) in 1954 did loans higher than 80 percent of value become available. That opened the ownership market to a much broader range of households.”

An Instrument of Canadian Housing Destiny

The Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) was created in 1945 to administer the NHA. Its primary concern in the immediate post war period was providing affordable housing for returning soldiers by providing low cost NHA mortgages. CMHC introduced mortgage insurance in 1954 to make it easier for veterans to buy or build houses. As we read above, with the plunge in house prices of the Great Depression still in mind, lenders and regulators had demanded a 25% down payment to protect them from losses in default. Saving this down payment was an arduous process for a young family, especially one where the father had spent years in uniform defending his country.

Over time, both NHA insurance and CMHC changed into something very different. They became instruments of national housing destiny. Housing became a public good, with Canadians and their politicians viewing housing and home ownership as part of the Canadian dream. Making housing “more affordable” became an unthinking and unchallenged part of the fabric of Canadian government. NHA insurance was extended from veterans to all homeowners. Coverage was expanded in 1979 to existing homes. The minimum down payment was dropped from 10% to 5% in 1992. As home ownership was integral to being Canadian, landed immigrants were permitted to buy a home with no Canadian credit history.

The Mortgage Insurance Company of Canada (MICC) began to provide private mortgage insurance in 1963 and there have been other Canadian private mortgage insurers over the years. MICC successor Genworth MI Canada Inc. and Canada Guaranty Mortgage Insurance currently hold mortgage insurance licenses. With the adoption of the Basel (BIS) bank capital standards in 1988, CMHC insurance, with a full Federal government guarantee, became a “zero risk weight” which meant a bank did not need to set aside any capital against a NHA insured mortgage. The Federal government agreed to “level the playing field” and back private mortgage insurers for 90% of their coverage to allow them to compete more fairly with government backed CMHC. Genworth Canada and Canada Guarantee currently share the $300 billion limit granted by the Federal Government under the Protection of Residential Mortgage or Hypothecary Insurance Act.

The minimum down payment remained the original 10% until 1992. In the aftermath of the early 1990s real estate bust, the Federal government introduced the First Home Loan Insurance program which allowed only a 5% down payment and funds from RSPs to be used for a down payment without penalty. All these changes meant the down payment or equity injected by a purchaser of a house was much lower. The “carrying cost” of a house began to dominate the purchase decision of buyers. With the Federal government assuming the downside risk, the prime consideration of buyers began to be how much of a mortgage they could finance.

Unthinking Nationalization

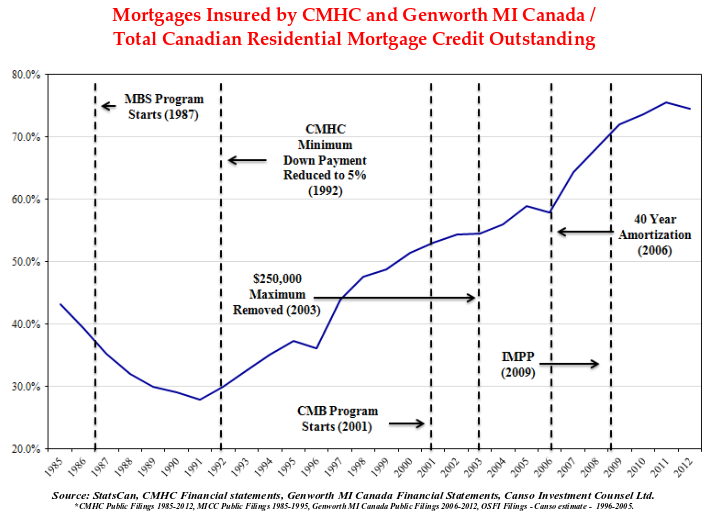

The participation of the Canadian government in the mortgage market has become massive. In the following chart, we show the residential mortgages guaranteed by CMHC and Genworth MI Canada Inc. as a percentage of the total Canadian residential mortgage credit outstanding. Although Genworth MI Canada is considered a private mortgage insurer, the Federal government has guaranteed any claim Genworth is unable to pay up to 90% in the event of insolvency. The approximate percentage of Federallyinsured residential mortgage credit has increased from 30% in 1988 to the present 75%. Conservative and Liberal governments alike have “nationalized” residential mortgage lending with-out giving it much thought until recently.

Note that from 1985 to 1990, the share of insured mortgages actually fell from 45% to 30%. The Mortgage Backed Security (MBS) program was created in 1987. This “securitized” pools of mortgages into MBS that could be traded on the bond market. In the mid 1990s, the MBS program took hold and the percent of insured mortgages increased from 30% to 50%, as smaller issuers were able to securitize high ratio mortgages.

Full of Balance Sheet?

The Canadian Mortgage Bond (CMB) program was then created in 2001. It allowed the Canadian banks to create NHA MBS and then deposit them into the Canadian Housing Trust (CHT) which would then issue bonds backed by the MBS. The CMBs were even more liquid and traded at a very small premium to Canadian government bonds. CMHC then removed the maximum $250,000 insured mortgage maximum in 2003. This really got things going as the banks could then securitize most of their mortgages. The banks paid the insurance premium to reduce the capital requirements of these holdings to zero in “balance sheet arbitrage”. As we have said in prior newsletters, this was an extremely lucrative proposition for the banks with the return on investment for this activity recently estimated by BMO Capital analysts at 62%! The attractiveness of this activity to mortgage lenders can be seen by the increase in insured mortgages from 55% in 2003 to 75% in 2013.

Adding to the increase from 55% to 75% was the implementation of the Insured Mortgage Purchase Program (IMPP) in early 2009. This recession fighting program allowed lenders to securitize mortgages into MBS and then sell them to CMHC at quite a tidy profit. Why the Federal government would assume all the credit risk of a mortgage and then buy it at a healthy premium as a “riskless” asset is an interesting question. The banks did not complain. A look at their financial statements in the 2009 to 2012 period shows they cumulatively reported billions of dollars of profits from “securitization” at a time when there was no private sector securitization to speak of. We believe the IMPP will eventually go down into the annals of Canadian history as a “stealth rescue” of the Canadian banking system that morphed the mortgage market into a credit bubble of immense proportions.

Relaxed Fit Mortgages

Much has been made of the harshness of the recent “tightening” of mortgage insurance standards by Finance Minister Jim Flaherty and the Conservative government. The real estate industry should really be thanking them for their largesse in the first place. Insured mortgages increased from 55% of mortgages in 2004 to 75% in 2013 under the Harper government. The relaxation of mortgage insurance underwriting standards was key. Even if a bank wanted to insure a mortgage, they still needed to meet the CMHC underwriting standards. CMHC relaxed their standards and made it much easier for borrowers to qualify:

1. CMHC removed the maximum insured mortgage of $250,000 under the Liberals in 2003. This pretty much created the conditions for “portfolio insurance” in bulk by the Canadian banks. Mr. Flaherty and the Conservatives came under much criticism for reinstating a “harsh” $1,000,000 insured mortgage maximum in 2012. Despite the howls of outrage from the real estate lobby, the move from $250,000 to $1,000,000 over nine years is a 400% increase, a compounded growth rate of 17% per year. To gauge the impact of this change, we suggest simply considering what would have happened if Mr. Flaherty had reinstated the $250,000 maximum of 2003 compounded forward at the 1.8% average inflation for the intervening 9 year period. This would have been $300,000 and all hell would have broken loose as this would have been lower than the average house price in most major Canadian cities! Even compounding at 10% gives a maximum insured mortgage of $600,000. Note that the credit crazed Americans, even given their credit depravity prior to the credit crisis, never removed the insured maximum mortgage for Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac.

2. CMHC increased the maximum amortization three times between 2005 and 2006. In 2005 they moved from 25 years to 30 years. Then in 2006, seeing competition from the private mortgage insurers (also backed 90% by the Federal Government) they lengthened to 35 years and finally to 40 years in November. The move from a 25 year to a 40 year amortization increased the amount a CMHC insured Canadian could pay for his or her house by 33%. Mr. Flaherty “prudentially” moved it back to 35 years in 2008, to 30 years in June 2011 and back to the 25 years where they started in June 2012.

3. The minimum down payment for a high LTV insured mortgage was 5%. CMHC introduced a 100% “financing product” requiring no down payment in November 2006. This has recently been “tightened” back to a 5% down payment.

4. CMHC also allowed an unlimited number of mortgages but then “tightened” things up by allowing only 2 mortgages per individual. CMHC has confirmed to us that they did not track how many mortgages an individual borrower has insured until recently. Note that if a bank insured an individual who had more than the allowed 2 mortgages after the limit came into place, CMHC could refuse this insurance claim. The additional complication is that there doesn’t seem to have been any coordination between CMHC and the two private mortgage insurance companies until recently.

5. The “Second Residence” program allows an individual to insure two residences. The second residence doesn’t have to be the primary residence of the insured, but must be accessible year round. CMHC has confirmed to us that this includes summer cottages. They also have confirmed to us that they do not track how many summer cottages they insure in their portfolio.

Everyone is Doing It!

You might be wondering what possessed a bunch of civil servants to create a mortgage mania. The simple answer is that they saw their raison d’être as making housing finance inexpensive for Canadians. It also made the politicians and voters happy. Besides, in the heady days of the credit bubble, everyone was doing it as a National Post article (our emphasis) from November 2006 explains:

“CMHC has just started offering insurance to cover mortgages with 40-year amortization periods. CMHC is also offering insurance on mortgages that cover 100% of home prices. CMHC and its private-sector rivals, Genworth Financial Corp. and AIG United Guaranty Mortgage Insurance Co. of Canada, have been gradually upping the ante through increases in the amortization periods since March. The Crown Corporation, which introduced 30-year and 35-year periods earlier this year, is making the new 40-year product available in response to demand from lenders, says Mark McInnis, a vice-president with CMHC. “We’re the third guys coming up to the plate with these products,” Mr. McInnis said. “AIG has done it, GE has done it. We’re just doing something that’s in the marketplace.”

Dodge-y Mortgages

As the National Post reported at the time, the changes to loosen up CMHC underwriting terms were quite popular with consumers. Not everyone was happy. David Dodge, then Governor of the Bank of Canada, was not pleased: “David Dodge, governor of the Bank of Canada, criticized CMHC earlier this year for potentially stoking inflation by offering to insure riskier products. Mr. Dodge was later reassured the new products would not lower mortgage qualification criteria.” It turns out that Mr. Dodge was right on the mark with his comments, but it was house price inflation that CMHC was stoking. Mr. Flaherty has now recognized this problem by rolling back these “innovative products”.

Postal Code Appraisals

Perhaps the most potent enabler of the housing bubble was the creation by CMHC of its automated appraisal system, EMILI, in 1996. The purpose of this was to allow lenders to quickly check if the house price involved in a mortgage transaction was reasonable. This “streamlined” the process of mortgage insurance and origination but it also removed any human check and balance. EMILI uses an “algorithm” which looks at the address, and particularly the postal code, and metrics of the house to be insured. The key variables are the square footage of the house and the prior sale prices for the geographic area of the house. It is our understanding from real estate professionals and bankers that there has been extensive “gaming” of this system and excessive prices generated by this system. If a higher price is required for CMHC insurance coverage, the square footage, which is input by the lender and supplied by the mortgage broker, can be increased as required.

A New Direction for CMHC?

There has been quite a “changing of the guard” at CMHC recently. The Federal government appointed Robert Kelly, a long time banker, as the new Chair of the CMHC Board of Directors. Karen Kinsley, who has been President and CEO of CMHC since 2003, is now retiring. These personnel changes might represent a major change in direction for CMHC. Ms. Kinsley’s entire career at CMHC since 1987 coincided with the increase of the securitization of mortgages and the extension of mortgage insurance. We also note the recent departure of the current CMHC vice-president of insurance underwriting, servicing and policy. “The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. confirmed that Marc McInnis, the Crown Corporation’s vice-president of insurance underwriting, servicing and policy, left this month. No reason was given.” Mr. McInnis seems to be the same CMHC vice-president who announced the creation of 40 year amortization and 100% financing products in 2006: “We’re just doing something that’s in the marketplace.”

You might find our interest in the management changes at CMHC a trifle obscure. It seems to us that by putting CMHC under OSFI regulation and making Mr. Kelly its Chair, Mr. Flaherty and the Federal government are now serious about turning CMHC into a real insurance company rather than a housing program backed by the unlimited guarantee of the Canadian Federal government.

Availability of Credit Created the Housing Boom

We have maintained for some time that it was “availability of credit” rather than interest rates, “the price of credit”, that has driven the recent hot housing market. As we saw from the chart of the percentage of insured mortgages, the increase in Canadian house prices to extraordinarily expensive levels has coincided with the extraordinary increase in government mortgage insurance. We examined this relationship and have generated some Canso charts that confirm our suspicions.

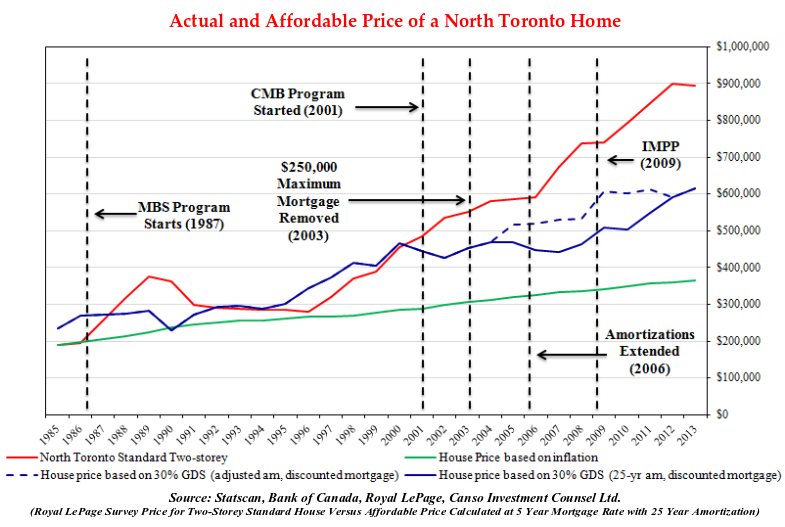

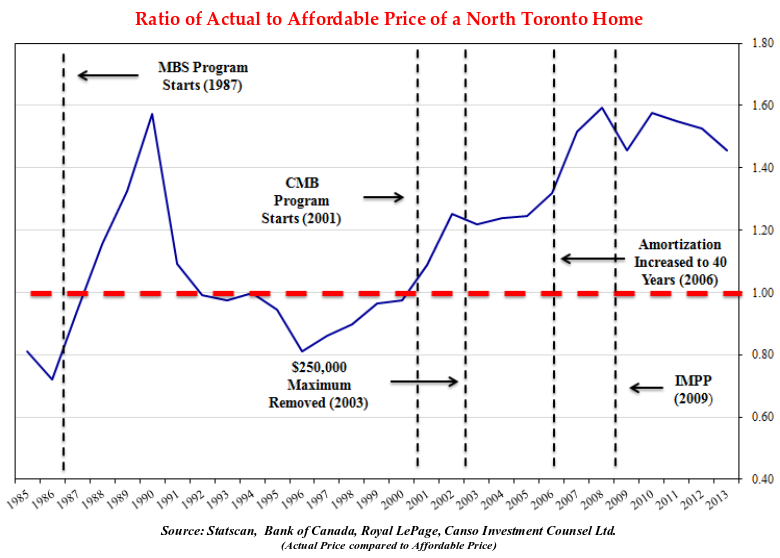

Housing statistics are notoriously presented selectively and “smoothed”. For our charts, we have used the Royal Lepage Survey of Canadian home prices which started in 1985. We used the price of a “North Toronto Standard Two Storey House” that we have called the “Actual Price” which is shown on the chart below as the red line. The current two storey standard home in North Toronto has an Actual Price on the Royal Lepage survey of $900,000. We then calculated our own Canso “Affordable Price” by taking 30% of the Statistics Canada Average Pre-Tax Income for a Toronto Economic Family and determining how large of a mortgage could be carried with this amount. For example, at present we calculate that with 100% financing a family could currently carry a mortgage with a 25 year amortization of $615,000. This Affordable Price is shown on the chart as the blue line.

The dashed blue line represents the period when the allowable insured amortization was increased from 25 years to 40 years and now back to 25 years. As can be seen in the chart, the dashed blue line indicates the primary benefit of the increased amortization was an increased Affordable Price that could be paid for a home. The green line is the “Inflated Actual Price”, the 1985 Actual Price adjusted for the increases in the Consumer Price Index.

What is striking about this chart is that, in the 12 years from 1985 to 1997, the Actual Price, Affordable Price and the Inflated Actual Price were all in a fairly close range. We were also not too surprised to see that the efforts of CMHC to make mortgage financing more available led to sharp house price increases. In 1987, the start of the NHA MBS program caused a sharp jump in the Actual Price above the Affordable Price. This coincided with the sharp run up in housing prices from 1987 to the peak in 1989 and then the crash in 1990. Once the bubble burst, the two prices converged and the Actual Price and the Affordable Price were quite close for most of the 1990s. The Actual Price and Inflated Actual Price were very close in 1996, indicating that the Actual Price had increased about the same as the increase in the CPI.

In 1995, the Affordable Price increased, reflecting the drop in mortgage interest rates which allowed a larger mortgage to be carried. The Actual Price rose as well, as families began to realize that they could carry a larger mortgage and paid more for their houses. Note how much both the Affordable Price and Actual Price of $450,000 exceeded the $300,000 Inflated Actual Price by 2000, reflecting the low mortgage interest rates of this period. The Actual Price and Affordable Price sharply diverged in the early 2000s, perhaps reflecting the looser credit standards of the run up to the Credit Crisis.

The introduction of the CMB program in 2001 and the removal of the $250,000 maximum in 2003 certainly didn’t hurt the Actual Price, which increased $100,000 to $600,000. The Affordable Price stayed flat at $450,000 reflecting stable interest rates and modest income gains. The real damning evidence on the effects of CMHC’s mortgage largesse is the period during 2006 when the amortization increased from 25 years to 40 years and the down payment was dropped to zero. The Affordable Price went from $450,000 to $500,000, while the Actual Price shot up from $600,000 to $750,000.

It was the IMPP in late 2008 that really hit the Actual Price ball out of the ballpark. As we have been speculating for some time, not only did the IMPP give large amounts of risk-free money to mortgage lenders, it also had a definite effect on the housing market. The Actual Price shot up from $700,000 to $900,000 while the Affordable Price only moved from $500,000 to $600,000, reflecting the drop in interest rates during this period.

A Rational Ratio

Just to make sure that we weren’t imagining things, we calculated the ratio of the Actual Price divided by the Affordable Price, shown in the following chart. If the Actual Price and Affordable Price were the same, this ratio would be 1:1 or appear in our chart as 1.0 on the right hand scale, indicated by the red dashed line. A ratio of 1.2 indicates the Actual Price is 120% of the Affordable Price and a ratio of .8 would indicate the Actual Price is 80% of the Affordable Price.

In the chart, you will see that the ratio starts out .8 in 1985, reflecting the Actual Price being lower or 80% of the Affordable Price. It then moved from .8 to 1.6 in the housing bubble of the late 1980s before falling back to .8 in 1996. The start of the CMB Program in 2001 moved it from 1.1 to 1.2. The removal of the $250,000 maximum in 2003 moved the Affordability Ratio up from 1.2 to 1.3. The “mother of all loosenings” was the lengthening of the amortizations in 2006 that jumped the ratio up to 1.6. The decrease in interest rates in the credit crisis caused a temporary decrease to 1.5 before the IMPP jumped things back up to 1.6. The recent drop to 1.5 reflects the recent decrease in interest rates as prices have held firm, i.e. the denominator, Actual Price, stayed at the same level while the Affordable Price increased due to falling interest rates.

The evidence is fairly telling. In our view, housing became more expensive for Canadians because of the misguided efforts of CMHC to make mortgages easier to obtain. A numeric explanation will help. We calculate the current Affordable Price for a Standard Two Storey in North Toronto to be $615,000. Subtracting this from the Actual Price of $900,000 tells us that CMHC’s mortgage largesse has caused a $285,000 or 50% increase in the house prices in North Toronto above what families can afford.

Borrowers Should Repay Loans?

We found it fascinating when the recent Federal Government “Prudential Mortgage Underwriting Standards” for Canadian banks included the curious demand that the lender “assess the ability of the borrower to repay the mortgage”. It also struck us as unusual that Mr. Flaherty, stated in a public interview that the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, Julie Dickson, had told him that the Canadian banks were not following their underwriting standards. Could it be that Official Ottawa is setting up the banks to deny insurance on poorly underwritten mortgages?

This is what happened in the U.S. in spades after the housing crash. Investment analysts who cover Canadian banks, mostly employed by the very same banks, are united in their opinion that a Canadian housing bust would be quite easy on the banks they cover. Their assumption is that the gracious $900 billion of CMHC and private mortgage insurance backed by the Federal government would cover the banks’ housing losses. In the United States, even though Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (“implicitly” guaranteed GSEs) were seized by the government and continued to pay mortgage insurance claims, the U.S. banks have paid hundreds of billions in settlement of suits that they poorly underwrote mortgages or misled investors. In our opinion, Canada will not be different.

Masters of Disaster

The Canadian banks and other mortgage originators might believe that they have served their political masters well in making mortgages easily available. If they think that Official Ottawa will give them a break they should look to the example in the United States. The Dodd Frank Financial Reform Bill, which aims to “reform” the financial system and avoid future financial calamity by hyper-regulating U.S. banks, was named for Congressmen Barney Frank and Chris Dodd. These are the very same two gentlemen who demanded subprime mortgages be made available to the masses and loosened up regulation of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to permit them to buy subprime mortgages.

How Bad Will it Get?

Our point is not that politicians are selfserving, which is obvious. We are very concerned that Canadian investors do not understand the extent of the coming housing and mortgage problems and its effects on the Canadian economy and financial system. Yes, it is true that Canadian banks have laid off a large portion of their mortgage risk to the Federal government through mortgage insurance. The real question is whether the banks will be able to collect on all of it. Bank analyst John Reucassell of BMO Capital markets has suggested if things get bad enough, “moral suasion” might be used to force the Canadian banks to rescue CMHC. How bad will it get? Very bad.

This Time Will Not Be Different

Canadians are convinced that “this time it will be different” because we’re Canadians and we want it to be. We look at our neighbours to the south with disdain at their banking and mortgage crisis and reject this out of hand. Even the eminent Paul Krugman buys the pitch that the Canadian banks are “boring”, which is high praise coming from a citizen of a country with “exciting” banks. With 75% of all Canadian mortgages now insured by the Canadian government, the tamed Canadian bank economists now question how a setback in the housing market could occur? “What is the catalyst?” they demand.

As Professor Krugman points out above, a severe credit crunch does not have to involve total banking and financial system calamity. The credit cycle is a “founding principle” of Canso. From our early days as lenders, we noted the powerful human urge to lend when everyone else was lending and to do absolutely nothing when everyone else was doing nothing.

We now know that Mr. Flaherty has cracked down on loose mortgage standards at banks. His “Prudential Mortgage” underwriting standards demand that Canadian banks form a committee of their Board to develop and implement lending standards for mortgages. As we said earlier, it is a bit mind boggling that a bank filled with credit professionals would have to be told to do this. On the other hand, with the Canadian government assuming all the risk, the previous challenge for a Canadian mortgage lender was creating mortgages as fast as possible. Think of all the posters on buses urging you to become more indebted by calling your friendly bank mortgage broker!

Mr. Flaherty’s Protection of Residential Mortgage or Hypothecary Insurance Act (PRMHIA) has also now put CMHC under the regulation of OSFI. It will now be treated as an insurance company, not as the Canadian “no money down” real estate miracle. After increasing insured mortgages to 75% of mortgages, the PRMHIA is now restricting CMHC to $600 billion in insurance and the private mortgage insurers, Genworth MI and Canada Guaranty, to $300 billion.

Interestingly, the act speaks to “outstanding principal balance” in terms of insurance in force. CMHC seems to be taking the original face value of the mortgages as their “hard cap”. Genworth, on the other hand, is taking the amortized principal amount as their cap. We asked the question of how they could be at $300 billion of insurance in force when the total amount allocated to private insurers was $300 billion and Canada Guaranty, the other private mortgage insurer, had $50 billion of insurance in force. Their reply was that they “believed” their amortized outstanding balance was $250 billion, although they admitted that they did not track this statistic. In the latest quarter, they announced that they now had revised their “estimate” to only $150 billion, as they had asked their insured clients for information on the outstanding mortgage balances. The Genworth stock shot up in price on this news as the increased capacity to insure was met with enthusiasm by investors. Our question was how an insurance company and its actuaries could have overestimated their insurance in force by $100 billion or 40%?

Dynamic Dynamite?

We have a few more questions on the actuarial side of mortgage insurance. We have also done some digging into the actuarial standards for mortgage insurance, specifically the Dynamic Capital Adequacy Test (DCAT). The appointed actuary of a federally regulated mortgage insurance company must file this report annually to the Board of Directors and OSFI. Despite the public purse backing both CMHC and the private insurers, they do not release this information publicly.

We were interested in how one would go about assessing the potential losses on insured mortgages. It seemed to us that when house prices were rising, there is not a problem. If prices were to fall it might be a different story. The experience of mortgage insurers in the U.S. during the housing crisis has not been good. In Canada, the CMHC received direct government support in the 1980s and again in 1997, after the early 1990s housing bust, as Professor Londerville pointed out: “CMHC did not have sufficient reserves to cover all its incurred claims, and needed government intervention to assure that it remained adequately capitalized.” MICC also was insolvent in 1993 in the aftermath of the early 1990s housing market problems.

DCAT is Out of the Bag?

Tracking down information on the DCAT is not for the faint of heart. Mortgage insurers do not disclose the details of this test, although we are told in their financial statements that their actuary has opined on the subject. The comforting words “stress test” and “scenario” feature prominently in the disclosure. What we can gather from the research we have done is that the mortgage insurers have a “vector” of losses that they use, with internal modifications. The losses are “stressed” to a “95% confidence level” using scenarios developed in economic models. We also understand that the guideline is a minimum of the past three to five years of “experience”. We have been told that housing price changes are not the most important variable in this model.

This smacks to us of the flawed approach to credit rating securitizations in the U.S. where a very short experience period with sub-prime mortgages was used to draw conclusions that proved to be absurd. Think of it, you look at the last three to five years of rising house prices, exclude the 5% “unusual” events, and look at default rates and losses given de- faults. You correlate the default rate to unemployment rates and economic growth. Everything looks great. One would think that housing prices would be the most important variable to consider. One would also hope that the actuary would look at the “stress scenarios” in the U.S. housing bust and Canada’s own experience in the housing busts of 1981 to 1983 and 1989 to 1992. From what we can tell from our “indirect analysis”, and since we have requested the DCAT directly from CMHC, Genworth and their regulator OSFI and been refused, the excluded 5% of scenarios just might happen and lead to “exceptional losses”. Clearly, if you don’t think prices can fall 30%, there is no problem as the mortgage insurance “models” seem to suggest. Based on the last time our Actual to Affordability Ratio was at 1.6, a 60% overvaluation, prices fell 30% from 1989 to 1995.

Why Are There Any Losses?

Our question is why there are any losses when housing prices have increased so much? There is “optionality” in housing prices. If you cannot pay your mortgage and your house is worth more than the mortgage, you sell the house, pay off the mortgage, take your profit and then rent a house. If your house is worth less than the mortgage, you should stop paying and abandon the house to the bank. This happened during the recent housing crisis in the U.S. where people handed their keys to the bank.

Not Remotely Bankrupt

Canadians make much of the fact that a lender, in all provinces except Alberta, can pursue people who abandon their houses for any outstanding amount owing. This might have been relevant when people didn’t buy the largest house they could with very little or even no money down. If you look at many homeowners in Canada, many have used all their funds to buy a house and have no other substantive assets. Thinking about the U.S. experience, those states who made it more difficult for lenders to seize and sell houses had the worst housing setbacks. Perhaps this shows that it is best to work things out quickly. The fall in house values will impact Canadians’ ability to borrow money as the value of their house as collateral drops. In Canada, if people are “mortgage prisoners” with very high mortgage debt and lower house prices, they won’t be spending like they are now. This will not make for a strong economy and employment, which will put even further downwards pressure on house prices.

Another complication at pursuing mortgage borrowers for losses on mortgaged houses is that RSPs have been bankruptcy remote since 2008. The Federal Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act was amended to exclude RSPs from the bankrupt estate and this takes precedence over provincial bankruptcy laws. RRSPs are the single largest financial asset of Canadians, other than their houses. When most people file for personal bankruptcy in Canada, which is increasingly easy, their personal assets are likely worth very little. Credit card lenders write off the outstanding balance of an account in arrears after 90 days for this very reason.

A Tax on Your Down Payment

A good gauge of the financial health of the Canadian homeowner might be the current state of the Federal government’s Home Buyer’s Plan. This allows home purchasers to fund their down payments by taking money out of their RRSPs. This plan seemed like a very good idea at the time but now it’s a bit of a nightmare for many of the people who used it. A maximum of $25,000 could be taken out of an RRSP untaxed to fund a house purchase. This was to be fully repaid over fifteen years or taxes had to be paid on the scheduled repayment amounts. Now 35% of the participants are not making the scheduled repayments and are paying taxes. This means they are paying 43% tax on the scheduled payment instead of making the payment which is not financially sound. This is not a very good comment on the financial capacity of these people. Considering that these people are savers who actually made a contribution to their RRSP, it does not auger well for their less prudent peers!

Arrears in Confidence

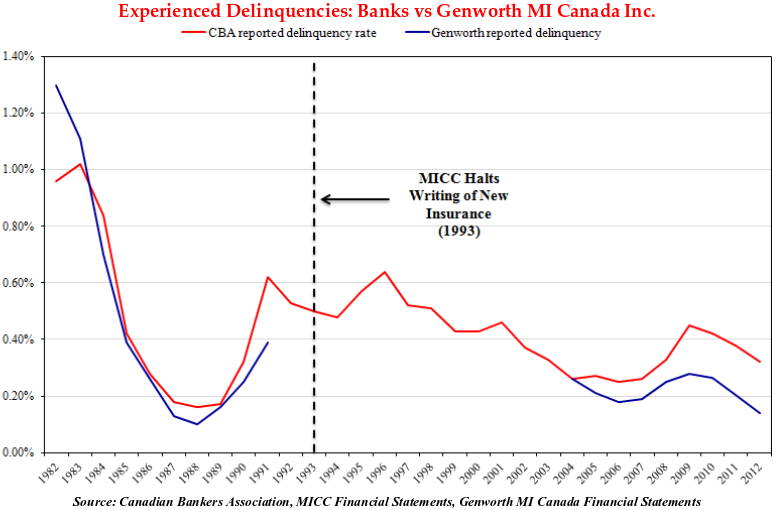

One of the most vocal arguments against a housing collapse is the current low level of mortgage arrears and losses. History doesn’t create a lot of confidence in this regard. In the chart above, we have examined the historical record of mortgage arrears in Canada. The Canadian Bankers Association “90 day” mortgage arrears is shown by the red line. The blue line is Genworth MI Canada from 2004 to the present and its predecessor, Mortgage Insurance Company of Canada (MICC), from 1982 to 1991.

What this shows is the current level of CBA mortgage arrears is very low at .32% which in our opinion reflects the sharp rise in housing prices. Note that arrears were even lower at .18% in the last Canadian housing bubble in 1988. The very disturbing thing about this chart is how rapidly the arrears increased from the .18% in 1989 to .62% in 1991. Note that this also occurred in the recent recession where arrears rose quite quickly from .25% in 2007 to .45% in 2009. We point out that MICC hit .4% of mortgages in arrears in 1991 and was in solvent in 1992. They were restricted from writing new insurance by the regulator. MICC completed the sale of the assets and contracts related to its residential mortgage insurance business in 1995 to a unit of GE Capital Mortgage Corp. for $15.3 million and sold the remaining assets to BNS for $11 million.

The current difference between the Genworth and CBA arrears is explained in Genworth financial disclosure by “mitigations” and “subrogation”. Mitigations are instances where the company “assists” the homeowner (including accruing and/or paying their interest) and subrogation is where the company assumes ownership of a house in a mortgage default claim. In these situations the mortgages in question do not appear in outstanding arrears. If these are added back, the Genworth arrears are fairly close to their historical relationship to the CBA arrears.

Taxi Driven Analysis

The facts speak for themselves in terms of affordability but what truly concerns us the most is what seems to be a very high incidence of mortgage fraud, tax evasion, and perhaps money laundering in the Canadian housing market. Like all things to do with the Canadian housing market, there has been a willful suspension of disbelief by all concerned. If it’s good for rising house prices or profits of financial institutions, we Canadians seem to be quite willing to look the other way. Lately, we’ve run across a couple of taxi drivers in the Greater Toronto region who have literally astounded and terrified us at the same time.

The first taxi driver was from Pakistan and lived in Brampton, home to a large Pakistani diaspora. In response to our question of “what is going on in real estate?”, he replied that he had been approached by “some people in the community” to buy a house and “make $50,000”. As the tale unfolded, it seems that real estate agents and some “investors” were buying houses and then reselling them at inflated prices. The increased price was caused by very high ratio mortgages, probably insured with CMHC and judged reasonable by EMILI. We suggested he steer well clear of this situation, as it constituted criminal fraud.

The next driver was an East Indian who said that the market was “weak” because people were unable to qualify for mortgages with the new mortgage rules. He said that it was rapidly improving as people sent their T4s, used for proof of income by banks, to India for “an increase”. Confused by how this worked, we asked for clarification and it seems that there are Indian companies who take Canadian tax returns and “restate them” at much higher income levels! Several mortgage brokers confirmed this “trick of the trade” to us.

Soft on “Soft Fraud”

Ben Rabidoux, an economic analyst specializing in the housing market, has confirmed to us that the banks, regulators and police don’t consider fraudulent information on mortgage applications to be a crime. They call this “soft fraud” which seems to be the “Canadian Way” for house buyers, especially immigrants, to obtain the maximum house possible. This rather benign interpretation of the Criminal Code might change with the angry national mood that we see after a housing meltdown.

Cleaning Up in Condos?

The runaway train of the Toronto condo market is something that troubles us greatly. The proponents of the condo boom point at the low vacancy rate in Toronto. We think a lot of the demand for “investment” comes from the real estate industry itself. One of our Canso staff rented a condo in a building where there did not seem to be many other occupants. The real estate broker showing the condo had other units of his own in the same building as investment properties. There are a lot of real estate agents and mortgage brokers who have joined in the party. The trouble is that their income is highly correlated to the prospects for the real estate market and will be dropping just when they need it to help carry their “investment properties”.

As with any speculative market, the market peak seems to be attracting leveraged speculation and naïve investors hoping to cash in on a “sure thing”. Another mortgage broker we ran across, told us about an “investor” client with 11 units that he could not now find mortgage financing for. Several young people we know of have also bought condos they do not plan to live in as investments. They are living with their parents and working as servers at restaurants and view their real estate speculation as a “way to get ahead financially”. For these investors, the cash yields on their properties are very low, once all expenses are taken into account. Cheryl King, a former Bay Street economist, published an Opinion article in the Globe and Mail where she looked at the economics of condo investing:

“Based on a 3.05 per cent mortgage rate, a fiveyear fixed mortgage with 20 per cent down-payment and 25-year amortization period requires a payment of $1,265 per month or $15,187 a year on an average condo, a 7-per-cent increase from just one month ago. Monthly maintenance, including utilities, will set the investor back conservatively $4,000 per year on a one-bedroom downtown condo. Take another $2,600 per month off for real estate and income taxes… All that is left is $535 per year, for a net rental yield of 0.16 per cent. And a repair or a paint job could wipe out that profit in a flash. The question becomes, why would an investor take on the risk of owning a condo for virtually no annual return?”

It is pretty clear that most investors in the Toronto condo market are focused on price appreciation. The problem with a “sure thing” investment comes when the price upside disappears and turns to downside. The combination of leverage and negative cash flow is not something the Toronto condo investor is prepared for. Liquidation usually occurs in a speculative market when investors are forced to cover interest payments on a declining asset value.

♪♪ ♪ Sell Me Quando Condo Condo ♪

Perhaps the biggest problem is that of the foreign investor in the Canadian condo market. Some investors in Toronto condos seem to be looking for a safe place to stash their cash. Most commentators view this foreign participation as beneficial. We are not so sure. Much of the money that is flooding into Canadian condos is from countries with economic, political and social issues. While it is flattering that Canada provides a safe refuge from oppression and social turmoil, some of these investors seek investment for funds of questionable origin. There are rumoured to be a lot of “cash transactions” in the Toronto market. When a condo buyer pays his deposit and contracts to buy a unit at completion, the deposit of the buyer is deposited into the trust account established by the developer at a Canadian bank. We’ve done some checking with those aware of anti-money laundering procedures of banks. It seems that a deposit by a foreign condo buyer does not receive much scrutiny. The money deposited into the trust account of the developer by a foreign buyer is treated as any other condo deposit. Like Russian deposits into the banks of Cyprus, this is not the most stable form of investment.

Blackout on the Grey Market

After much public angst about the speculative frenzy in the Toronto condo market, CMHC was moved to action and commissioned a survey of the condo assignment “grey market”. As Tara Perkins reported in the Globe and Mail (our emphasis in bold), it seems that the development community was not willing to expose its practices to outside scrutiny:

“An effort to get more information about the influence of some speculators in Toronto’s condo market has collapsed after developers refused to take part, leaving policy makers in the dark… Urbanation officially called off the study Tuesday, after the vast majority of developers who were asked for information did not give it… Ben Myers, executive vice-president at Urbanation, said he sent the survey to more than 100 developers that had launched condo projects in the past five years, asking them for either the percentage of units or an exact number of units that had been assigned before the condo buildings were registered. “We wanted to know what’s happening with this shadow market; there’s no real way to track it,” he said… He said that one person he spoke to, outside of the developer community, speculated that “because some of the people assigning units are not paying capital gains taxes on that, developers may not want the government looking into that any further.”

It’s Hard to Accentuate the Positives

Canso recently attended a real estate conference on the Toronto condo market, put on by the Capital Markets area of a Canadian bank. The idea of the conference seemed to be to calm nervous investors, but the evidence presented showed they should be terrified. A condo developer outlined the sales of whole floors of condos to ethnic and foreign investors for “investment”. He went on to say that investors in his latest development were having such trouble getting mortgage financing at the branch level that he had to appeal directly to senior management of a bank to have them financed. He also went on to say that the new condos coming onto the Toronto market in 2014 were far in excess of demand.

The Hockey Obsessed Turn Housing Obsessed!

Now that you have read our analysis and had a chance to consider our evidence, you might now be convinced that all is not rosy in the Canadian housing market. This is your logical right brain. In your heart of hearts, you do not want to believe it. You probably own a house, like most Canadians, and it is probably your most significant financial asset. Emotionally, you want to believe that your house in North Toronto is really worth $900,000, not the $615,000 you could afford to pay for it.

There was a story in the Toronto Sun “Hot property, hot topic (1)” that we came across at a barber shop. It discussed a survey by Zoocasa which identified “a growing obsession with the housing market”. Fully 84% of respondents said they think about real estate on a regular basis. Another 34% described themselves, a friend or family member as “obsessed”with real estate. The best quote: “The figure went up to 47% in the Toronto area, where respondents said as many people were talking about housing as about the NHL playoffs.” Dr. June Cotte of the Ivey School of Business said in a news release that our homes are often seen as an extension of our identity and represent who we are. She also said that owning a home is status which people like to broadcast! We Canadians are in love with our houses. This is very dangerous, as it is much like the complacency at the height of stock market boom. When was the last time you heard someone bragging about their stock portfolio, as you undoubtedly did before the dot.com meltdown?

CBC Declares the Real Estate Slow Down Over!

The CBC National News ran a story about the “good” June CREA sales numbers on July 4th. It was a bit of a “triumphal” piece, with someone tossing down all the negative magazine covers and headlines quite dismissively. It declared the slowdown over, due to these “positive” monthly numbers. It also featured a real estate agent and her frustrated clients who had lost a bidding war. The message was clear. Get back in because it’s “up, up and away”.

You might wonder why Canada’s national television broadcaster would run such a biased piece, given the actual underlying numbers. This is pretty normal for a market top. People want to believe in the “Canadian Miracle” in banking and real estate. The CBC editors and reporters probably have all just bought very small and very expensive condos to live their “urban cool” dream. Michael Lewis, in his book Boomerang, recounts that nobody in Ireland wanted to hear about the problems in Irish banks and real estate. This is very, very normal for a speculative market top and is what we call the “willing suspension of disbelief”.

Change from One Million??

Over history, lending on financial asset value inflates prices as increasing collateral values causes increased investor confidence and increased willingness of lenders to lend against the inflated values. We think we have demonstrated fairly clearly that it is access to insured mortgage credit that has caused the Canadian real estate and banking miracle. Our suspicion has recently been confirmed by a big rush into houses priced at $999,999.99. The National Post re- ports (our emphasis):

“The market for homes under $1-million has become “red hot,” agents say, and that’s at least partly because new rules brought in by Ottawa last year make it impossible to get a loan backed by mortgage-default insurance if the property is valued in the seven figures… The result: Bids for $999,999, or close to it, are increasingly common as even some wealthy would-be homeowners struggle to secure the necessary financing under new government rules.”

As we pointed out earlier, the removal of the $250,000 maximum insured mortgage was what really allowed Canadians to overpay for their houses. With an EMILI appraisal in hand and government backed mortgage insurance, Canadian mortgage lenders rushed to lend the most that they could. As Mr. Tal of CIBC put it: “it was almost a crime not to take a mortgage”. Given today’s rush to borrow under the $1 million insured mortgage limit, just consider what would have happened if, as we said earlier, the limit had been reinstated at $300,000, the $250,000 original maximum insured mortgage brought forward for inflation.

What of the vaunted “soft landing” in Canadian residential real estate? Well, suffice to say that this has never happened in any real estate market that we know of. Busts follow booms, as overleveraged speculators are forced to sell into a declining market. Why do many Canadians believe in ever rising house prices despite the growing evidence to the contrary? It’s because they want to believe and seek out comfort from those with similar views.

How Much is at Risk?

A real question for the Canadian economy and financial system is how the $900 billion mortgage guarantee could affect the solvency of the Federal government. In days gone by, before the credit crisis, sovereign credit was unassailable. On the Federal government books, the $900 billion is combined with other “insurance programs” as a Contingent Liability.

At March 31, 2012, insurance in force relating to self-sustaining insurance programs operated by three agent enterprise Crown corporations amounts to $1,589,869 million ($1,473,068 million in 2011). The Government expects that all three corporations will cover the cost of both current claims and possible future claims.”

This means that the government doesn’t expect any losses beyond the capital of these companies. Is this reasonable? Well, we’ve shown that MICC, Genworth’s predecessor, went insolvent when mortgage arrears went from .15% to .4% from 1988 to 1992. CMHC also had to be bailed out by the Federal government after both the 1980s and 1990s housing setbacks. How does this impact Federal government finances? Well, this liability is contingent, which means it doesn’t show up as debt on the government’s books. The current Federal government net debt is $676 billion and combines with outstanding provincial net debt of $512 billion for a total of $1.2 trillion. Clearly, the $900 billion in mortgage insurance backed by the Federal government is not a trivial amount.

It is true that some recovery will be made by selling the insured houses to cover the defaults, but this depends on house prices. Our analysis of the loan to value ratios for both CMHC and Genworth suggest that approximately 8% or $70 billion of the mortgage insurance written is on homes more than 90% LTV. This increases to $200 billion for LTV’s 80% and above. If prices dropped 30% to 50%, this contingent liability would very quickly develop into a direct liability as it did in 1997.

Avoiding the Obvious

The tendency of humans to avoid the obvious in their financial follies is well documented. In his fine book The Path Between the Seas, historian David McCullough recounts the collapse of the Compagnie Universelle which was building a French canal in Panama. Many ordinary French investors had invested all of their life savings in this venture:

“For hundreds of thousands of people the fate of the company meant the difference between the chance of real security for once in their lives and absolute financial disaster. If the company were to fail it would indeed be… the largest most terrible financial collapse on record, a stupendous event historically; but for the vast majority… it would very simply mean a personal disaster of almost unimaginable proportions… Strangers met and mutually strengthened their faith (in the company) with words of comfort.”

Questioning Home Ownership?

One question that the policy makers should be asking themselves is whether all this mortgage mania was really worth it. Surveys have shown that Canadian banks and businesses are risk-averse compared to their international peers. Diverting excessive invest- ment into residential mortgages and creating huge risk free profits for banks certainly creates housing investment. This adds to statistical GDP growth but lowers investment in other areas. Certainly, no politician wants to be against the Holy Grail of home ownership, which recently has been questioned by academics. The negative experience in the U.S. with very high levels of home ownership has focused some research in this area.

The New York Times reported on a study by David Blanchflower of Dartmouth University and Andrew Oswald of the University of Warwick. The study showed that a high level of home ownership leads to lower labour mobility and is “inhospitable to innovation and job creation”. Although homeowners have lower rates of unemployment than renters, the unemployment rates for the entire population were higher in areas with higher rates of home ownership.

“The professors say they believe that high homeownership in an area leads to people staying put and commuting farther and farther to jobs, creating cost and congestion for companies and other workers. They speculate that the role of zoning may be important, as communities dominated by homeowners resort to “not in my backyard” efforts that block new businesses that could create jobs. Perhaps the energy sector would be less freewheeling in North Dakota if there were more homeowners… Homeownership, in economists’ jargon, creates “negative externalities” for the labor market.”

While examining the virtues of home ownership is certainly beyond the scope of our research efforts, it certainly brings into question the “all in” nature of the Federal government’s bet on residential housing. We worry about the financial aspects of this bet and the dire effects it could have on the Canadian economy and financial system. As we said earlier, a Canadian population mired in mortgage debt with house prices “under water” would not be in a happy place for economic growth. They would be “flipping out” rather than “flipping houses”.

Let’s Hope We Are Wrong!

Like the ordinary French who invested in the Panama venture, ordinary Canadians are desperately hoping that all the negative analysis and experts are wrong. A collapse in real estate prices would indeed be a “personal disaster of almost unimaginable proportions” for many Canadians. Since estimates show upwards of 30% of the Canadian economy depends directly and indirectly on real estate, problems in Canadian housing will spill over into many other parts of the economy.

We hope very much to be proven wrong, but the analysis is clear. Canada borrowed its way out of the 2009 Recession by stoking our residential housing market to absurd levels. We cannot afford the houses we are living in.

“The Canadian housing race driver, “Jumping Jim” Flaherty, stepped on the gas and the overheating engine laboured to accelerate. As the car entered the last straightaway, smoke began to rise from the engine compartment. A few grinding noises and the screech of abused metal didn’t distract Flaherty. He kept his foot to the floor, hoping to gain the momentum to coast to the finish line. As flames began to shoot from the engine, Flaherty shifted into neutral, hoping that he would coast over the finish line before the car exploded…”