The Eye of the Bond Beholder

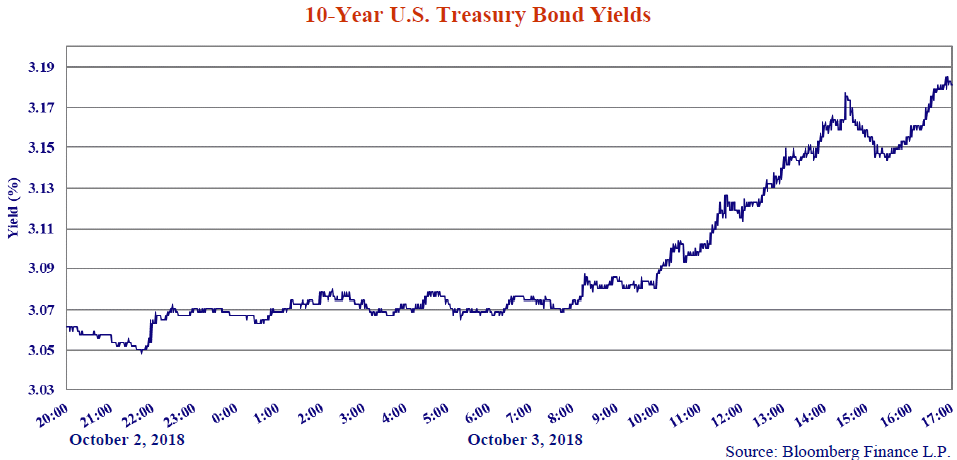

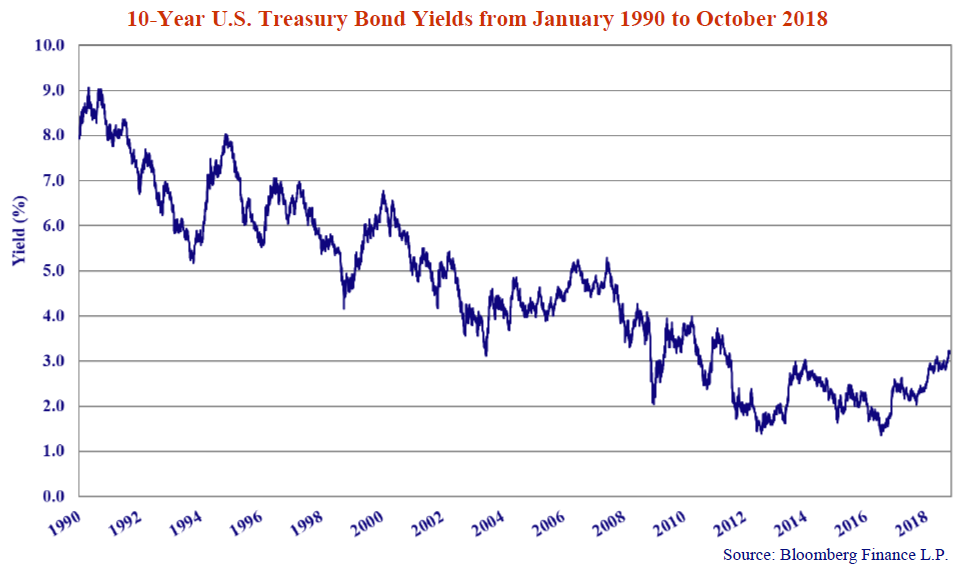

We are usually surprised at the lack of surprise of other investors at things we consider ominous. Lately, we have been perplexed and worried about the current market apathy at the steady uptrend in bond yields. A case in point was the reaction of the financial media to the jump in yields on Wednesday, October 3rd. As the chart below shows, reacting to strong U.S. economic data, the 10-year U.S. Treasury Bond yield surged by over 0.1% or 10 bps (where a basis point (bps) is equal to 1/100 of 1%) to over 3.17%. It has since continued further upwards and is 3.25% at the time of writing.

Hotter Yields and Hot Dogs

This was a big move for the bond market, but the media response to it was underwhelming. It wasn’t the case earlier this year in April, when the 10-year UST yield moved above 3% for the first time since 2011. There were dire headlines and much expert commentary that the “economic end was nigh” because of rising bond market yields. This time around, there were a few articles on yields making new highs but nothing panicked or hysterical. The media headlines that day were mostly about the strong economy and the rising stock market. The Bloomberg website, the Go-To source on things financial, had its headline stories about the Kavanaugh Supreme Court drama, the Trump family tax scams, pot producers and the Amazon minimum wage response. The increase in bond yields was relegated to Bloomberg’s Opinion columns.

By the next day, the stock market was down on higher yield fears, but the popular press continued to be silent on the subject. Our browsing confirmed that CNN was still breathlessly covering the political fight over Kavanaugh’s nomination. Despite the downdraft that day in the stock market, the higher bond yields didn’t even make the first page of the CNN website. The leader for the feature stories of the “all-new CNN Business” section covered “Costco’s secret weapon: Food courts and $1.50 hot dogs” and “I spent 53 minutes in Amazon Go and saw the future of retail”.

Admittedly, our analysis of the financial media is imperfect. As boring bond managers, we understand that bonds are not considered exciting, but when hot dogs are better for CNN readership than soaring bond yields, we are more than a little bit hurt. The important thing we take from the difference in reactions between now and when yields first rose over 3%, is that the market has become jaded about higher yields and their possible impact on the economy and markets. This is what we suspected would happen. When the party is going strong, nobody worries about the hangover the morning after, and we suspect that this is the case at present.

Just prior to publication on Wednesday, October 10th, the stock market had begun to pay attention to rising bond yields. The S&P 500 was down 3.3% and the Nasdaq 100 was down 4.4% on the day. Bloomberg had as its lead story “U.S. Stocks Plunge Most Since February” and reported that even President Trump had noticed the rising bond yields: “Trump Says Fed ‘Has Gone Crazy’ Following Stock Market Selloff”.

Apart from President Trump’s inelegant jawboning of the Fed, the interesting thing to us was that in prior stock market sell-offs, bond yields had dropped on the “Fear Trade”. On this sell-off, bond yields were down just 3 bps to 3.17%, a smidge over the 3.16% they had surged to on October 3rd.

Bond Price and Prejudice

We admit to our prejudices. It is our rather prudish role to remind financial partiers of the risks inherent in their behaviours. We like to start with the basics. We therefore remind you that interest rates and bond yields are the price of money, what people have to pay to borrow the capital they require. Interest rates are very important to our capitalist economic system and the financial markets that allocate our capital. Changes in interest rates change the economic decisions that people make every day in business and their personal lives.

The one thing we have been telling you for quite some time is that central bankers made money extraordinarily cheap over the past few years. Way, way too cheap. Nominal interest rates and bond yields went down to historical lows and even went negative in Europe and Japan. As our clients and readers know, we think yields are now normalizing after a long period of monetary policy absurdity.

The trauma of the 2008 Credit Crisis psychologically scarred central bankers after they allowed and even cheered on the “financial innovation” that caused the financial havoc. Their trigger word was “crisis” in its many financial and political varieties. These formerly stodgy financial bureaucrats morphed into economic superheroes and quantitative easing and negative yields were their recipe du jour to fight all economic enemies, real and imagined.

Monetary La, La Land

These central bankers created their own monetary “La, La Land”, where their previous financial orthodoxy was replaced by “anything goes”. Bond market investors also suspended their disbelief and became true believers in the financial catharsis of low and even negative yields.

Other people got used to the extraordinarily low interest rates but not us. We were not convinced of this “New Abnormal”. We marveled at the cheapening of credit and emphasized how unusual this was in recorded financial history. There have been low and negative “real” interest rates when inflation was higher than nominal interest rates, but we could not find other historical periods when actual interest rates were so low.

An Outstanding 264 Years

Our belief that the low interest rate hysteria was a historical anomaly was confirmed to us in 2015 when the British government redeemed its Consol bond issues, which were first issued in 1751. These were perpetual bonds with no maturity, bearing coupons of 4% that were issued to fund the aftermath of the South Sea Company financial bubble and the Napoleonic wars! Generations of British financial bureaucrats were happy to leave them outstanding for 264 years, but interest rates were so low in February 2015 that the Brits called these bonds. They then called the remaining Consol issues bearing coupons of 3.5%, 3%, 2.75% and 2.5% over the remainder of 2015. The long-suffering Consol holders were happy to get their money back. One older lady who inherited the bonds from her parents recalled that she was getting her 2.5% in the 1970s when British interest rates hit 20%!!

A Wacky Yield Summer

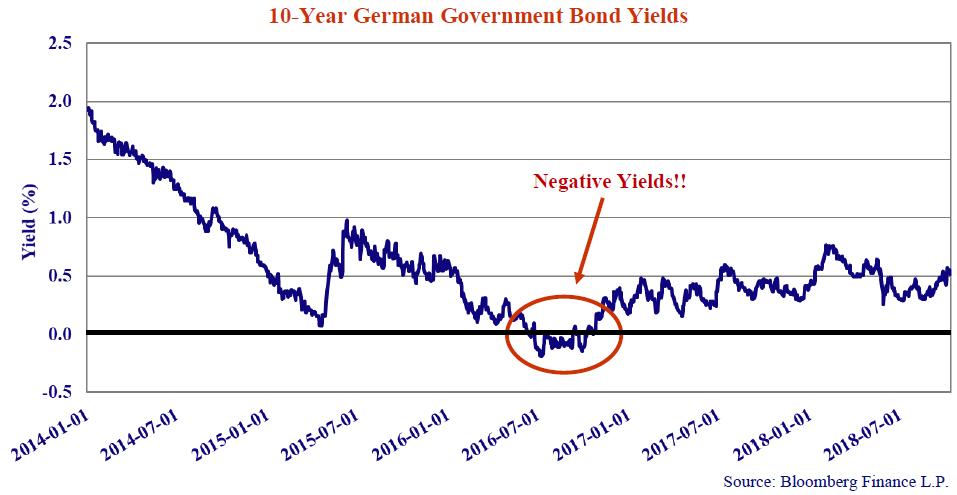

Bond yields reached their lows in the summer of 2016, reacting to the serial debt crises in Europe and the British Brexit vote.

As the chart above of the 10-year German government bond yield shows, yields actually went negative for a wacky few months in the summer of 2016. The “financial experts” were talking at the time about the obvious rationales for this monetary idiocy, which stoked our rhetorical fires. A mere two years ago, in these very pages, we railed at this financial abomination in our October 2016 Market Observer:

“The Greatest Fools Are Running Things

The “Greater Fool” investment theory postulates that when the price of a financial asset soars well above its fundamental value, the price appreciation is due to the prospect of a greater fool buying it from the foolish owner.

By their own admission, the publicity-seeking and experimental economists running today’s central banks are now the Greatest Fools of all. They are buying bonds with no regard to their price or value in their desperate attempts to improve their economies with ultra low and even negative bond yields.

Bond portfolio managers are watching this financial inanity with trepidation but most are bowing to performance pressure and holding on to their very overvalued bonds…

There is incredible complacency about the effects of the current experimental monetary policies. We can’t help but think this is a contrarian indicator of serious import. Investors believe that the tsunami of money flowing out of central banks and into the markets will continue forever. This is despite the constant assurances from the Federal Reserve that it will indeed slow its production of money and raise interest rates.

No One Knows

People are confused. Both sophisticated and very naïve investors alike are asking us to explain “the meaning of negative yields”. Our response is simple: no one knows, not even the central banks creating them. Negative nominal yields are a very recent phenomenon with no historical precedent…

Where does this put the bond market? Our take is that we are still in a long period of bottoming bond yields. How negative can bond yields go? Not that negative, as obviously there would be an unlimited supply of bonds if borrowers were paid handsomely by lenders to issue them. The same goes for consumer interest rates. Very negative interest rates on consumer savings would end up with cash in mattresses and safety deposit boxes.”

Historical Folly

Now that negative yields have proven to be the historical folly that we thought they would be, we are not taking a forecasting victory lap. Far from it, we are terrified for the great investment masses that have no idea that their fixed income holdings are in for a drubbing.

Our readers also know that we believe that the cheapening of credit has distorted the efficient allocation of capital. Excess liquidity has created an immense “stretch for yield” in the credit market that is not going to end very well. We don’t need to go into examples, given the lengthy diatribes that we have previously written on the debauched lending standards in the Leveraged Loan and High Yield markets. It is suffice to say, that the assumption of risk seems to have become a goal in itself, where the intent is to “get invested” and not to require a return commensurate with the risks assumed.

It is striking to us that many economists and market strategists are now telling the Fed that they should “take things slow”. Were these same experts counseling central bank caution when yields were absurdly low and negative? No, of course not. As we have told you many times, cheaper money is way more popular than tighter money. Our question is that with yields not much more than prevailing inflation, even after the latest increases, where do these experts think yields should be?

Pedal to the Monetary Metal

In the good old days before the Credit Crisis, most economists were monetarists. They had learned the economic lessons of the 1970s that Keynesian debt, deficits and fiscal stimulation had limits. The then economic orthodoxy was that excess money supply would simply result in excess inflation. Naively by today’s economic beliefs, prevailing interest rates were thought to be related to the prevailing inflation rate.

The economists of today, after their overexposure to financial crisis fighting, now seem to believe that interest rates are a simple accelerator mechanism that should perpetually be “pedal to the metal”. This conceptual independence of yields and inflation is a thing of wonder to us. What happened to the quaint notion that “real interest rates”, market interest rates less inflation, should provide a positive return to the lenders of capital?

Ruminating on Yield Ruination

This rumination on yield ruination got us thinking about the personal context for yields. Many of us older folk at Canso have experienced higher yields but many investors haven’t. The current crop of bond traders and bond portfolio managers who started work after 2008 have only seen yields drop to generational lows over the last ten years. Those of us old enough to remember the rising yields of 1987, 1994, 1998 and 2007 are viewed as ossified fossils of the bond market. Except perhaps for Warren Buffet, the generation of investment professionals who were working during the last protracted period of rising yields in the 1970s has long ago retired.

Context Me??

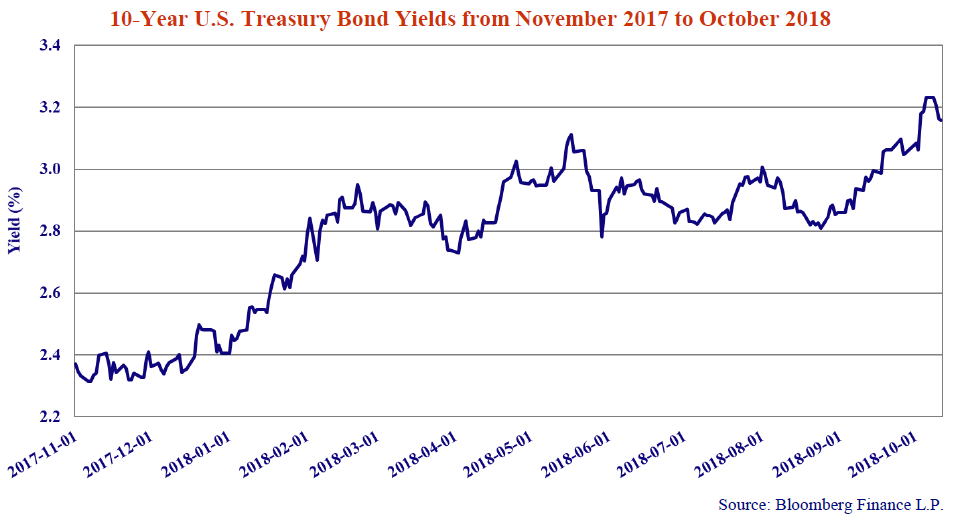

Context is very important to understanding what is going on. If you haven’t “Been There, Done That” you probably will be “Done Like Dinner” in an investment sense. We have assembled several more charts to make our point. Our initial chart of this issue showed the sharp increase in yields of 0.1% on October 3rd. The chart below shows the increase in context of the last year, with yields rising from 2.35% to 3.19%, an increase of 0.84%.

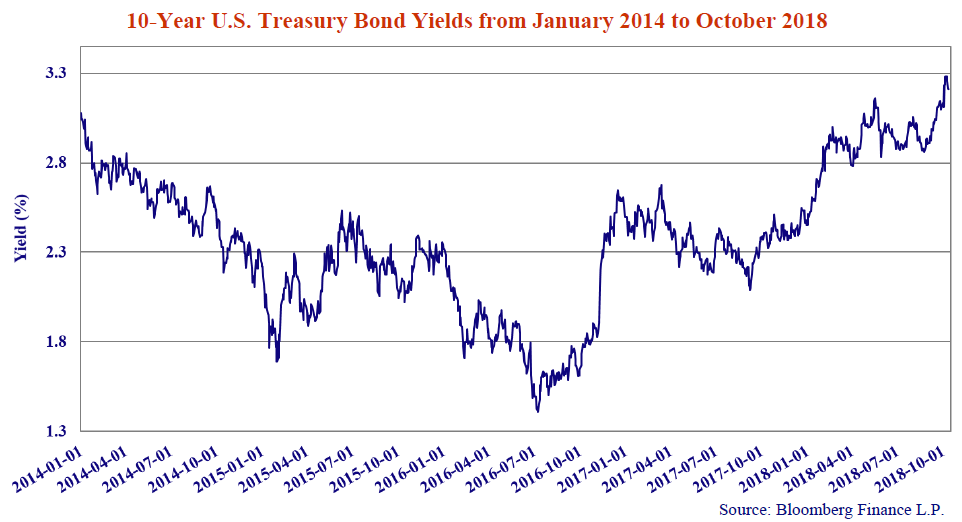

All of this seems dramatic but as we say, context is very important. The 1.45% low in the 10-year UST yield was achieved in July 2016, as the chart below shows. This was just after Brexit, as serial financial crises caused central banks to proverbially cry “Uncle” and throw everything they had into their ever more desperate attempts to save the financial world.

After this “Big Easy” in monetary policy, the course for yields has been up ever since. We can see from the chart of the 10-year UST yield above, that the current 3.19% is the highest it has been since 2013. On the other hand, we are not too far from where we started when the panicked central bankers started their group anxiety attack.

Not Exceptional

Now we’ll look at the longer-term chart below, starting in 1990. Once again, the historical context does not generate panic. We can see that 3.19% is not exceptional. It just gets us back to where we started out in 2010 before the Euro Debt and Brexit central bank panics.

Inspection of the chart shows us that yields are still well below the 4% plus level that persisted before the Credit Crisis in 2008 when U.S. inflation and U.S. economic growth were similar to where they are now.

So now that we’ve provided you with some context on yields, you are probably thinking that your trusty Canso market observers might be onto something with their radical thinking that bond yields might actually continue to rise.

Plumbing History??

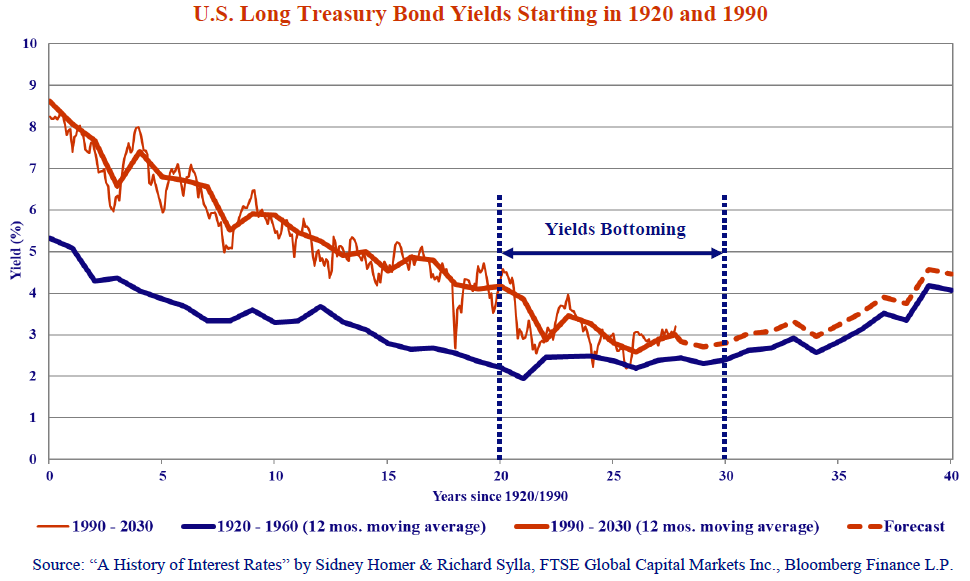

As always, we have a little more context for you. You might remember our interesting chart of the long-term U.S. T-Bond yields that we have updated below. This compares long U.S. T-Bond yields in the 40 years from 1920 to 1960 to the current pattern beginning in 1990 to present. As we have told you before, this came as a result of our efforts to plumb history for guidance on the yield hysteria of the past few years.

Dropping Returns and Yields

Initially, we looked at the behavior of the long-term U.S. T-Bond yield during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The very interesting thing to us was that, contrary to popular understanding, yields were actually dropping prior to the Stock Market crash of 1929. It occurred to us that this might have resulted from all the military productive capacity created for the First World War that was then put to civilian use, that then caused returns on investment to drop.

We also realized that this was what happened when the Cold War ended in 1989 and Western nations diverted their large military expenditures into a “Peace Dividend”. The productive capacity was expanded even further when Communist China joined the international trading system and became a global manufacturing powerhouse.

When we plotted the two 40-year periods together, we were struck by the similarity in yield patterns between them. In the Depression, the current low in yields was reached in 1941, 21 years after the start of yield period.

We think that the low in yields in the current pattern and the secular low for a generation of investors was reached in July 2016, 26 years after the start of the current cycle.

If you inspect the graph closely, you will see a surprising similarity between the two yield patterns between years 20 and 30. We show the actual yields with the thin red line and the 12-month average with the thicker red line. The actual low yield in the current experience has come later, but the moving averages seem to be following much the same bottoming pattern. If the current experience continues to follow the historical precedent, it looks to us like the path for yields will be upwards for many years.

A Period of Interest Rate Infamy

While we hesitate to “distort history” for our own ends, the historical parallels are self-evident. Yes, we cannot call the exact bottom, but we’re pretty confident that the summer of 2016 will go down in financial history as a period of interest rate infamy. Our grandchildren will be wondering what the heck we were thinking when we bought bonds at the extraordinarily low and even negative yield levels during the 2010s. Like the protracted period of yields bottoming in the 1930s that our grandfathers experienced, we think the 2010s will prove to be the experienced low yields for a generation.

We have spent a lot of time on the spillover of rising yields in our past newsletters so there isn’t much point to elaborate on these further.

In terms of Canada, we think the future path of yields is also upwards, except that we are starting from a position of lower Canadian yields than U.S., which again is not historically normal. Since the U.S. dollar is the global reserve currency and the largest global economy, Canadian bond yields are usually higher than U.S. bond yields. At present, Canadian yields are lower, as international investor perceptions have been positive on the Canadian economy and banking system since the Credit Crisis. In our opinion, given our view on the speculation in Canadian residential housing, this is bound to reverse at some point in the not too distant future. If the 10-year Canada yield moves from the current 0.6% below the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield to the historical 0.25% above it, Canadian yields could very well end up rising 1% more than U.S. yields.

Suffice to say, it looks to us like yields will be rising for some time to come!