We had quite an extended discussion in our last Market Observer in April on the low level of interest rates. We ended by saying: “The good news is that despite the gloom and doom, things don’t look all that bad economically in the U.S… We are not sure when or why the Fed will raise interest rates, given their amazing prevarication on the subject.” Both of these statements were on the mark, as the U.S. economy continues to chug along and the Fed found Brexit as another reason to avoid raising interest rates further. Our repeated belief was that it might take a while for interest rates to find a bottom but our take was that the downside risks of a rate increase to a bond portfolio were greater than the potential upside from further yield decreases.

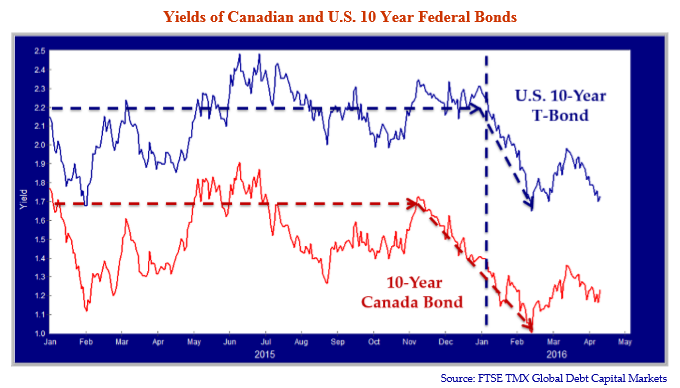

We couldn’t have been more wrong on that over the 2nd Quarter of 2016. Interest rates fell far lower than we expected on market fears when U.K. voters unexpectedly backed leaving the European Union. The chart above shows the sharp decrease in Canadian and U.S. 10-year bond yields after the Brexit referendum fiasco. Stocks, especially financials, and high yield bonds also took a swan dive in price after the Brexit result. Apart from the British stock market, however, equities recovered in time for quarter end but bond yields stayed at their lows. At the time of writing in early July, equities have sold off again and the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield in the U.S. has just made a record low of 1.367%. The 30-year U.S. Treasury yield has dropped to 2.14%.

We’ve gone back to consult A History of Interest Rates for guidance on the subject of how low interest rates can go. In a Chapter entitled Detail of the Great Bull Bond Market 1920-1946, it shows that the lowest yield on long-term Treasuries was 1.85% in 1941. Perhaps it’s appropriate that Britain stood alone in 1941 against occupied Europe until Pearl Harbor brought the U.S. into the war.

Britain Stands Alone

Britain is now standing alone against a furious Europe that is not impressed with the spanner that British voters threw into the EU gears. The problem is that Britain is now leaderless since Prime Minister Cameron has announced his resignation and is leaving the EU exit negotiations to his successor. Under EU rules, the U.K. gets to decide when to submit its request to leave which it does not seem in any hurry to do.

The uncertainty over Brexit is not good for the financial markets. There is already mayhem in the British financial markets as its bank and real estate stocks are getting clobbered over recession worries and the British Pound has fallen to record low levels. Mark Carney, the Canadian who is now Governor of the Bank of England, has spoken about the significant risk of recession and has promised ample liquidity and looks ready to lower interest rates, which is adding to the woes of the British Pound. Real estate investors realize that the significant financial role of the City of London would likely be reduced as financial institutions are forced to locate significant parts of their operations within the remaining EU countries. Several U.K. property funds have recognized this and just marked down their property valuations and suspended redemptions.

Britain Will Take Its Time

We were discussing the recent financial market disruption at a Canso meeting and came to the conclusion that anyone who thinks they understand what is going on is delusional. Given that polls now show that most British voters who backed exit from the European Union really didn’t think it would happen and all the experts were wrong in their predictions, the current meltdown in the British economy and financial markets must be quite a shock. It could take a while for anything to happen since Britain loses considerable leverage as soon as it formally files with the EU to leave. The clock starts ticking and Britain is out after two years, no matter what has or hasn’t been negotiated unless the two-year period is extended by the mutual consent of both the UK and the remaining EU. This means it could be some time until Britain formally applies for exit from the EU. The problem for Britain is that the uncertainty in the meantime is terrible for their economy and financial markets but the alternative is to be ejected with limited say on how it happens. The uncertainty also gives Britain some leverage over the EU which wants things done quickly.

Buying Negative Income

The worldwide plunge in yields after Brexit has taken the already negative government bond yields in Germany, Switzerland and Japan further into negative territory. This means an investor pays more for a bond than he or she will receive at maturity, giving a certain loss unless interest rates go more negative, delivering a capital gain. Why would this happen? Some investors need long term bonds to match their liabilities, financial institutions are forced to hold government bonds by regulation and most importantly, central banks are buying their government bonds for “Quantitative Easing” programs, i.e. buying as many as they can to get the price up and they don’t care if the yield is negative because they think it helps the economy by making more money available for spending.

Downwards Pressure on Financial Income

As we have said before, low interest rates mean less money for savers to spend. This is especially a problem with aging demographics in most developed economies. Retirees are dependent on their financial income and pensions that invest in the bond market. Lower interest rates directly reduce their spending. GDP (Gross Domestic Product) equals GNI (Gross National Income) so lowering interest income puts downwards pressure on GDP. Capital gains on bonds, real estate and stocks offset this to some extent in GNI but benefit the wealthy, rather than the average citizen.

Signaling Recession?

The real question is whether the U.S. bond market with its low yields and flattening yield curve is signaling recession. This goes against the equity market rally, the current high equity valuations and the frenzy in the credit markets. This was not the case during the Great Depression of the 1930s. As described in A History of Interest Rates, credit spreads were very high during the period of very low Treasury yields during the Depression:

“…the very high risk rates of interest that simultaneously prevailed during these years (period of low Treasury yields). It was a period when a large part of the liquid capital of the country (U.S.) attempted to crowd into the always limited area of riskless investment.”

We see people currently crowding into riskless investment in government bonds, but we also have low credit spreads on many opportunities. We recently looked at a CCC bank loan yielding 2.75% above a LIBOR floor of 0.75%. We think that 3.5% for a very risky loan does not show a high level of fear or an evident credit shortage. Even the European Central Bank is now buying corporate bonds as part of its QE program.

Whether interest rates go up or down over the next few months is anyone’s guess. The U.S. is still turning in decent economic performance but the Fed is unlikely to raise rates post Brexit unless the economic damage is mainly limited to the U.K. or U.S. inflation increases.

It is very hard for the financial markets to not perform well with all the liquidity the world’s central banks are creating. Now that the Fed is on hold, the equity market seems destined to avoid a major sell off which begs the question of why yields are at Depression lows. Perhaps there’s a major financial crisis in the offing, China perhaps, to justify the extraordinarily low yields in the global bond market but credit spreads and equity markets don’t seem overly concerned.

Negative Canadian Real Interest Rates

To us, the current 10-year Canada yield of 0.98% does not seem to be adequate compensation for any uptick in inflation, especially since the current Canadian CPI is 1.5% and has averaged 1.6% since 2007, before the Credit Crisis. Of course, further drops in yields will generate capital gains and bond managers are desperate to avoid underperformance. With the current FTSE TMX Canada Universe yield of 1.77% and average bond mutual fund fees of 1.5%, some capital appreciation is needed to justify investment in a bond fund. The stretch for yield into credit is certainly justified with the FTSE TMX Canada Federal Non-Agency Bond Index yield at 0.91%.

The low yields could also mean that we are in for a Depression with serious deflation. In the low yield period of the 1930s, inflation was actually quite negative. A 2% yield combined with a -4% deflation rate for a 6% real return. For now, bond investors are happy to do what they have done since 1981 and ride their bonds higher in price as yields drop, even though they are not compensated for inflation since real rates are negative on most government bonds. With the current Canadian CPI of 1.5%, the “robust” 0.98% 10-year Canada yield makes for a certain -0.52% real return over 10 years if inflation stays at this level.

How Much Does it Cost to Lend Money??

Will all yields go negative on all bonds if the central banks keep up their QE? This would see a world where borrowers and issuers are paid to create debt for the slavering savers and investors. Who would not want to be a borrower and who in their right mind would want to be a lender?

Sticking to Our Knitting

As we said earlier, anyone who says they know how all this is going to play out is delusional. We’ve added value to our clients’ portfolios since 1997 by not getting too wrapped up in macro events. The approach that works for us is to be paid a fair price for taking on risk, and to not take the risk if we are not paid. The pressure to change is normally greatest when it is the worst time to do so and we firmly believe our approach will continue to succeed in the future.