Procrastination as a Virtue

Despite the vociferous urging of our client service colleagues, and they are rather good at being vociferous, we ran quite late with this edition of the Canso Corporate Bond Letter. Our more observant readers have probably noticed that the masthead on this edition is May 2015 versus April. As we typically get the Corporate Bond Letter out a week or two after the Canso Market Observer, which was published in early April, we are indeed tardy in our authorship.

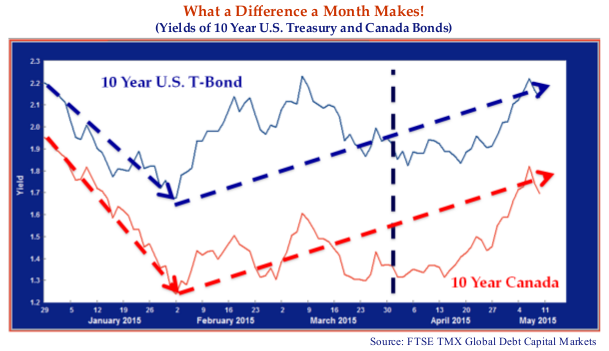

We must admit to more than our normal share of dallying and navel contemplation with this edition. We weren’t happy with our creative recipe and something was definitely lacking in our ingredients. Our delay turned out to be a rather good thing for these pages, however, since most of what we wrote in early April is now completely and utterly irrelevant. How so? Well, we always say that a picture tells a thousand words and the chart below destroys about a gazillion of them, including our working draft.

Plunging Yield Lines

As inspection of the chart above shows, global bond yields plunged unexpectedly in January with the 10 year U.S. T-Bond declining by 0.5%. By March 31st, yields were up from the lows but bonds still had a pretty good quarter due to price appreciation. Those bond managers with longer duration portfolios had great performance but they did not have much of a chance to celebrate. Yields reversed their entire year-to-date decline by early May.

Our problem was that we had dedicated our original draft to lecturing our patient readers on the ridiculously low level of bond yields. We warned that, despite the fascination of the investment fashionistas with deflation and negative yields, the actual risk was that yields would unexpectedly rise.

Now that yields have risen, our original draft is hopelessly dated. Yes, it would have been good timing to go to press before yields had reversed their decline. What would have been amazing perspicacity to the reader in early April would now seem like rear view mirror forecasting.

The Unintellectual Discussion Genre

We do have ample cause for smugness as we fixated on the potential for rising yields in our very timely April 2015 Canso Market Observer. For those of you into Japanese anime and foreign language films with sub-titles, we highly recommend it for its discussion of negative yields in Europe. The story of Herr Rippoff and German bond yields is a classic example of the Canso genre of unintellectual financial discussion.

Our belief at the time (which now seems to be vindicated) is that the plunge in yields in the first quarter terrified bond portfolio managers who were short of their duration targets. Falling yields and rising bond prices in 2014 had meant substantial underperformance for portfolios with a shorter duration. Anybody who was in this predicament probably threw in the towel in the first week of February when yields were still falling and bond prices rising. They just wanted the pain to end.

As the dashed blue arrow shows in the chart above, when the last person threw in the towel and bought bonds in early February, yields began to climb back up. We have marked March 31st, the end of the quarter, with the vertical dashed line. You can see that yields were above their lows of January but were still substantially down. This made bond managers with longer duration portfolios quite happy.

Longing for Yield

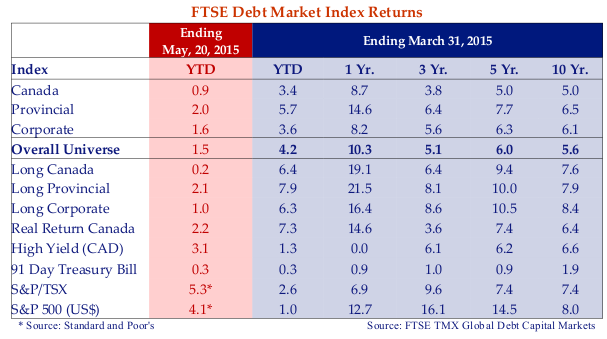

Yields actually fell more in Canada than in the U.S. on the back of the Bank of Canada’s unexpected rate cut in January. This drove the already meager yields on Canadian bonds to even lower levels. Falling yields resulted in higher prices and very positive returns for the Canadian bond market in the first quarter as the table below shows.

Mr. Poloz’s Very Expensive Lesson

Deflation fighting was in. Central banks around the world joined the Bank of Canada in lowering rates in the quarter. The pre-emptive deflation fighters included Australia, India, Israel, Thailand and even Uzbekistan. To prove its chops as a global provocateur extraordinaire, Russia head faked, first raising and then lowering rates just to keep everyone guessing.

Bank of Canada Governor Poloz, in an attempt to explain the inexplicable, justified his surprise rate cut as added “insurance” against a potentially weakening economy due to the “oil shock”. We wondered why he hadn’t raised rates during the oil boom using the same logic but, then again, lower rates are always more popular than higher rates. With the U.S. Federal Reserve poised to raise rates in the second half of 2015 we, and it seems most of the world, expected the BOC to stand pat as U.S. short-term interest rates moved up.

This would have created looser monetary conditions in Canada without an overt policy move by the BOC. The Canadian dollar plunged in the wake of the rate cut and Mr.Poloz learned a very expensive lesson for little economic gain. As a Western client pointed out to us, with oil falling from $100 to $50 per barrel in the latter part of 2014, a 25bps rate cut does not do much for oil dependent Alberta. Even an impossible 250bps cut would not have turned the revenue cash taps back on and sent workers back to the oil fields.

The hoped for manufacturing boost in Ontario and Quebec, the big potential benefit of a lower Canadian dollar, will take some time. Shuttered factories will not be reopened overnight. Corporate planning processes take time and the average company devastated by the strong Canadian dollar will wait to ensure the Canadian dollar depreciation is for real.

The Kamikaze Canadian Real Estate Investor

In our view, the Bank of Canada rate cut benefitted only one group in Canada – Kamikaze Canadian real estate investors. They were big fans of Mr. Poloz’s move and more houses probably traded over asking price to the financially imprudent in Toronto and Vancouver’s overheated markets. Unfortunately, when U.S. rates finally rise and Canadian rates inevitably follow suit, many overextended Canadian borrowers will experience the downside to leveraged financing.

Since interest rates are the price of credit, one might wonder why the Bank of Canada bothers to complain about rising consumer debt when they are making it so attractive to borrow. It’s a bit like a drug pusher complaining about his clients’ drug use when he’s raising the potency and addiction potential of his drug to hook them. The Bank of Canada’s ultra low interest rate policy engenders “ultra stupid borrowing” with people borrowing far beyond their means. The Canadian consumer borrower’s policy seems to be to borrow as much as their current income will carry in interest payments. The problem with this is that interest rates and payments will eventually rise.

We continue to worry about the lunacy in the Canadian residential housing market. Mortgage rates could easily double from current levels and the problems with Canadian consumer debt are getting worse. As the bank and real estate apologists put it, “people buy payments” and right now there is no problem since interest rates are so low. This will not always be the case.

As we’ve explained many times in past editions, the “normal” levels of short-term interest rates are fair value at inflation plus 1-2%. With current inflation of 1.0% this implies short-term interest rates of 2.0-3.0%. A positively sloped yield curve implies long rates of 4.0-5.0%. This means that even with a flat or 0% inflation rate, bonds are now fully valued in the 2% range.

What Goes Down…

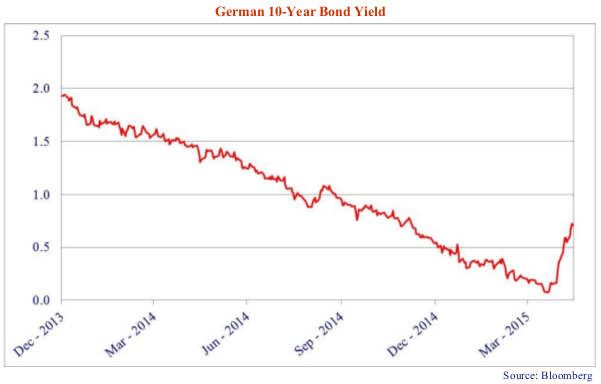

As we said on the previous page, much had been made of the collapse in government bond yields across the globe until they shot back up in May. Nowhere was the fall in yields more acute than in Europe, as can be seen in the chart below, where the European Central Bank QE bond buying drove German government and other countries’ bond yields into negative territory.

Die Yield Lunatiks

The chart above depicts the yield on a ten year German bond. This shows how much the European financial markets took leave of their senses. This dipped to 0.08% in April at the low before recently rocketing back up to 0.7% in May. As we wrote in our April Canso Market Observer, despite thefashionable investor fascination with negative yields, this only occurred because of investors taking advantage of the “Greater Fool” European Central Bank who guaranteed to buy bonds at negative yields.

The yield lunacy was stunning. We were taken quite aback when we calculated the spread on the European Investment Grade Corporate Index at 98bps versus an actual yield of 92bps. This was due to the negative -.06% yield on European government bonds (figures as of March 31). We think even legendary trading crazies Nick Leeson and Jereome Kerviel might have paused for a reset before diving into a European corporate issue at the yield lows.

It is said that timing is everything and those rushing to the European bond exit in May waited a tad too long. The .6% increase in yield on a 10-year German Bund saw its price fall by over 5% in May. Of course the holder who bought at the April low yield of .08% got a very healthy one basis point or .01% (.08%/12 = .007% rounded up) in yield for the intervening month to offset his loss!

We have frequently made the point in our last few newsletters that there is little yield generated from bonds at current prices to offset capital losses. Bonds have always been seen as a “safe” alternative to stocks and we think that this view will increasingly be tested if yields finally do rise. Janet Yellen might have recently reflected on the overvaluation of equities but at least they have earnings yields much higher than bond yields and the prospect for increasing cash flows.

As we have said since the founding of Canso, overvaluation can persist for very long periods and one will never know when or why the sentiment will change. We’ll never know why bond yields sharply increased in May and certainly few people other than us were worried about rising yields just before it happened. Complacency is usually required for a sharp market move and we had complacency in spades in the bond market in the first four months of 2015.

Money For Nothing and the Risks Are Free

We think that the real damage has yet to be done. Low bond yields, static credit spreads and lengthening duration all add up to a toxic cocktail for those drinking the consensus low yield Kool Aid. Investor apathy has now given way to shocked inaction. When risks appear, the exuberance and heightened risk-taking of testosterone gives way to cortisol and fear. As John Coates points out in his great book The Hour Between Dog and Wolf, the physiology of trading means that cortisol is now starting to exert its sway over markets. Traders and bond managers are starting into the catatonic phase where “sitting on your hands” is preferable to doing something.

The yield on the Canadian Corporate Bond Index at 2.0% also doesn’t provide much of a cushion with an index duration of 6.0 years. A 1% rise in yields would reduce the price of the average bond in the Corporate Index by 6%. This means it would take 3 years for the yield of the index to offset the fall in price of the index. The longer a bond’s term, the more sensitive it is to interest rate changes. If and when rates start to climb the impact on longer dated securities (and indices) will be dramatic.

High on Yield??

If you’re not a fan of investment grade bonds in a rising rate environment, the boosters of “junk bonds” or below investment grade debt are quick to offer their wares. The sales pitch of those that hawk high yield bonds for a living is that investors focused on “income” should buy a high yield fund, clip coupons, reduce their interest rate risk and ride off into the sunset! At the peak of the credit cycle, this always seems like a low risk proposition.

The reality always turns out to be different as the downturn of the credit cycle wreaks its damage. Much money has been lost on the “running yield” from the hypnotic stream of promised high yield cash flows. Remember that high yield is by definition “speculative debt” that is rated below investment grade. The “safety” part of the sales pitch seems like a good plan until the interest payments stop and the price of the bond falls from $100 to $25.

Through the Yield Grinder

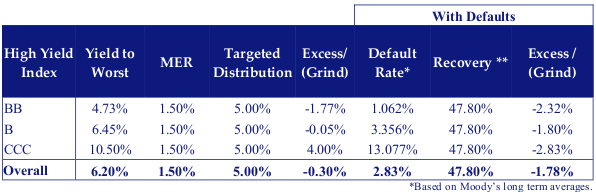

Consider the data presented in the table below. An income oriented fund comprised of high yield securities might target a 5.00% distribution. The running yield on the BAML High Yield Index is 6.20%. Subtract from this an estimated 1.50% MER and the 5.00% distributions and presto, the Fund NAV is reduced 30bps.

Factoring in defaults on the portfolio makes a considerable difference to the experienced return. The long term average default rate on non-investment grade securities is 2.8% with an estimated 47.8% recovery rate. Assuming only the historical average default rate and recoveries the Fund NAV is reduced 1.8% per year. We expect that defaults will rise and recoveries will be lower due to the recent deterioration in the structure and covenants of many new issues. We have written about this extensively in previous Corporate Bond Letters and we believe the default experience going forward will be much worse than the historical levels cited.

It is a very seductive thing to reduce portfolio credit quality and/or utilize leverage to increase the running yield of a portfolio. The chart above shows that even in today’s robust credit markets it is very difficult to maintain distributions at positive levels.

Nothing From Nothing is Nothing

The dramatic impact on a portfolio from defaults is the major reason Canso spends so much time analyzing deal structure and recovery value. The list of casualties in the oil and gas sector is growing and now includes Connacher Oil and Gas and Southern Pacific Resources. Shareholders and lenders, particularly unsecured lenders, face some tough days ahead.

We have frequently cautioned in past editions about high yield bonds of Canadian energy issuers that allowed almost unlimited senior ranking debt in front of the unsuspecting bond investors. There are many things we don’t like but watching bankers take our security is top of the list.

Historically, the MLX High Yield Energy index traded 96bps tighter than the overall High Yield index. Today the High Yield Energy Index trades at a 261bps premium to the overall index, prompting many to declare a huge buying opportunity. We are unconvinced and to badly paraphrase Billy Preston’s lyrics, we think that subordinated lenders will likely extract “nothing from nothing is nothing”.

My How You Have Grown

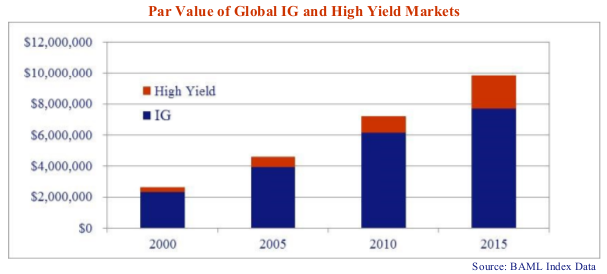

The global fixed income credit markets have continued to grow, as you can see from the chart below. The par value, or the original principal at issue, of outstanding investment grade and high yield corporate bonds is approximately US$10 trillion. Since bonds increase in value with falling interest rates, the market value of outstanding debt would be even higher. Canso estimates the total global corporate credit markets exceed US$25 trillion when bank loans, floating rate notes, private placements and short-tem securities are included.

The previous chart shows that the value of the high yield markets has more than doubled to US$2.2 trillion over the past 5 years. In comparison, the investment grade market only grew a more modest 24% over the same period. We believe this reflects the regulatory changes put in place after the Credit Crisis of 2008.

An essential part of the regulatory bank de-risking has involved the migration of lending from bank balance sheets to the capital markets. Banks now originate loans and sell them to third party investors like bank loan mutual funds and ETFs. The recent resurgence of aggressive balance sheet activities such as leveraged buyouts, dividend recapitalizations has also accounted for part of this growth.

We must admit to viewing this development with some foreboding. As we have said in past editions, this mechanism essentially has the banks arranging loans for very sophisticated financial operators and funding them with sales to mutual funds and bank loan ETFs funded by unsophisticated retail investors. It also involves open-ended funds with daily withdrawals investing in extremely illiquid bank loans. This will not end well.

Herd Across the Pond

Canso sent a two-person team of highly trained “Overt Operatives” to London in March for an infrastructure conference and a wee bit of hobnobbing. The Romans decided 2000 years ago that it made a nice location for an outpost so we thought an investment reconnaissance mission was in order. During their Overt Op on the fabled streets of London they met with smooth-talking politicians and fast-talking traders from various financial houses.

They understood about 4% of what people were saying but constantly nodded in the affirmative. They also heard a lot about the impact of the ECB’s Quantitative Easing program, the implementation of which coincided with their arrival. Everyone knew QE was coming but apparently no one realized it was coming.

Traders and strategists talked of falling rates, negative yields and tight spreads and the need to access beta (pronounced “beeta”) in pursuit of alpha (pronounced “alpha”). Everyone thought the markets had gone mad but most feel it better to be at the party than not. A few people sheepishly admitted inflation in Europe was likely going to pick up and things weren’t quite as bad as they seemed.

No one really talked about Greece except as a vacation destination. It is guaranteed that things are going to end badly (at least in the markets anyway) and everyone admits it but that is a problem for later because everyone who was long was getting rich. A bright eyed young strategist from a global bank suggested there might be a pull back around Victoria Day weekend and that could be our opportunity to “get in”. We set a reminder in Outlook.

No one in England talks about cricket anymore but no one would tell us why. We feigned interest in the election that was supposed to be too close to call until it happened. Everyone seems to have had lunch with the Governor of the BOE who is Canadian you know! He must be exhausted.

Wanna Buy a Watch?

The overt team members learned about blowout high yield financings for Wagamama (a restaurant chain) and Merlin (a theme park operator). We have marveled in previous Corporate Bond Letters about the mania in the USD leveraged loan markets and the willingness of investors to accept both lower returns and weaker protections. Europe has apparently caught the same QE fever and then some.

Many high yield companies can borrow money in Europe for sub 3% which we think makes Bombardier’s recent USD 10 year deal at 7.5% look pretty good. There are 14,000 registered investors in Europe (excluding Belgian dentists) and all of them are going the same way. 13,765 of these are frantically re-writing their investment policy statements to allow them to take advantage of the hot market.

We learned that investors regularly get shut out of deals – syndicate people hand out zeroes all the time as if it is a badge of honour. It was mentioned Mexico issued a 100 year Sterling bond last year. Only 99 more years to go until you get your money back-fingers crossed. The bond is bid without offer meaning everybody wants to buy but nobody wants to sell. As we write this letter Mexico just borrowed 100 year money in Euro for the first time.

Every once in a while one of the fast talkers caught our operatives off guard by asking what we thought. While they were checking messages on their Blackberry’s we flexed up and replied we were very concerned about the impact of falling WTI on the Toronto condominium market. After a long pause everyone agreed Canso is on to something.

What are you doing here?

In the immediate aftermath of the credit crisis governments and supranational agencies scrambled to encourage companies to spend and lenders to finance this spending. In the absence of functioning credit markets schemes were developed to finance private sector and quasi-public sector spending. One such scheme was the European Investment Bank Project Bond plan.

These schemes make sense when critical infrastructure spending lacks available private sector finance. As the credit markets returned to health these programmes are crowding out the traditional investors in a not very healthy way. We highlight a recent example. The EIB just lent National Grid plc £1.5 billion. Suffice to say management of National Grid were tickled pink not to have to pay commercial rates for money.

In the mad dash to extend credit we find the incursions of supranationals into commercial lending to be less than helpful. Individuals and companies should be able to borrow money at rates indicative of their ability to repay. We think extending credit to companies at subsidised rates distorts the credit markets in a way just as perverse.

Shama Lama Ding Dong

In the 1978 classic Animal House, the fraternity brothers of Delta House threw a toga party when they were placed on double secret probation-why not? If you are already so far gone that you can’t recover why not push the limits even further and go down with a smile on your face.

We think the bond markets are in the final stages of an extended binge. Negative yields, excess leverage, loose covenants and supranationals crowding out market based financing all make us cringe. The binge period will be followed by a period of rising rates, higher defaults, lower recoveries and eventually we believe a return to more conservative lending standards until the next time around. Investors will come to the sobering realization that rising rates can and will produce significant losses for holders of longer duration assets and lax lending standards will cause substantial write-downs of ill-conceived credit assets.

Proving Bunkum is Bunkum

We believe at Canso that the financial markets are inherently human and thus very inefficient. This seemed a rather outmoded and quaint belief when we started Canso in 1997. At the time, the efficient market theorists held most investors in their thrall. Ten years later in 2007 they had eventually convinced all the politicians, central bankers and regulators that markets should just be allowed to take their course and to stay out of the way. Remember “light touch” regulation and Alan Greenspan’s “Great Moderation”? The Credit Crunch of 2008 proved our point but 7 years on in 2015, most of this lesson now seems to have been forgotten.

The work of Professor John Coates and others on the psychology and physiology of trading gives academic justification to our rather quaint notion of a credit cycle. Our profitable observation is that when money is too cheap, people waste it (Mr. Poloz, take note). We also believe that investors get punch drunk from their success at the peak of the cycle and accept incredible risks they don’t and can’t understand. At the bottom of the cycle, they will be too scared to do anything and that is when a disciplined investor with ample capital makes considerable money.

Nobody now believes that markets are efficient, as the credit crisis obviously proved otherwise. Financial economists are busy proving why all of their previous bunkum is indeed bunkum. Regulators are also busy trying to reregulate the very banks they deregulated not so long ago.

We wait the eventual tightening of monetary policy in the U.S. with a morbid fascination. It won’t take much of an increase in interest rates for the bond market to be in considerable distress, as the recent sharp move up in European yields has shown.