“Some Days are Diamonds… Some Days are Stone”

So sang John Denver in the July 1981 cover version of this Dick Feller tune. The emotional highs and lows of a bond investor’s relationship with the financial markets were in evidence this quarter. July and August 2014 yielded diamond days for fixed income investors as bond yields fell, moving prices and returns higher. All the market indices then turned to stone in September as yields climbed, credit spreads widened and stock markets swooned.

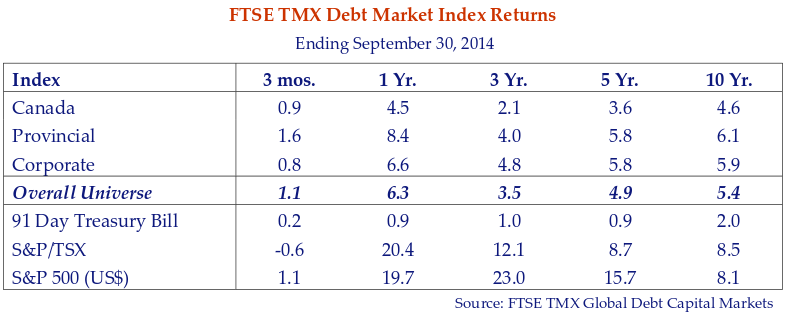

Canadian government bonds returned 0.9% in the 3 months ended September 30th, despite a negative -0.5% return in September. Longer duration provincial bonds declined a more severe -0.9% in September but again benefitted the most from the decline in yields over the quarter, generating a strong 1.6% return. Corporate bonds generated a respectable 0.8% over the quarter, even with the negative -0.5% contribution in September.

The S&P/TSX generated a negative -0.6% return for the 3 months ended September 30th including a negative -4.0% drubbing in September. The S&P/ TSX still returned an impressive 20.4% over the past year. The S&P 500 U.S. equity index recorded a positive 1.1% return for the quarter and a healthy 19.7% for the year.

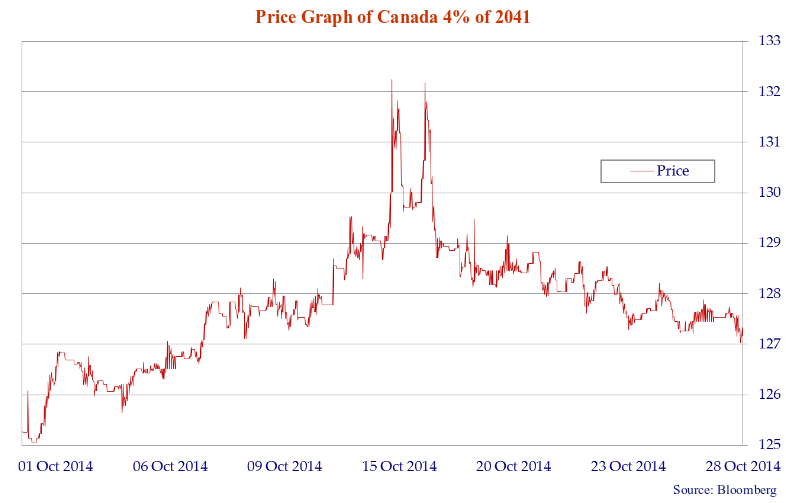

Market uncertainty continued into October, the traditional month for market upsets. Global stock markets sold off further, with major indices giving up much of their gains year-to-date. The bond market benefitted, as the inevitable “flight to quality” caused long Treasury and Canada bonds yields to plunge and soar in price. The following chart displays recent price changes of the Canada 4% of 2041. The $4 spike in price from October 14th to 15th corresponds to a significant drop in the equity market. Note that as the equity market rallied in the latter part of the month the price is almost back to where it was before the stock market’s conniption. Transactions at the peak of the market are likely the most desperate investor buying for fear of missing an even higher move.

“Back and Forth Froth”

To Canso, this type of “back and forth” trading highlights the futility of attempting to time short-term price movements. As we frequently explain, we think it impossible to predict the short-term future for interest rates or the price of any financial asset for that matter. Our profitable observation is all assets tend to revert to normalized valuation levels over time. Expensive securities become cheaper and cheap securities increase in price. Are bonds expensive or cheap at these levels? Well, when yields fell there were many experts available to explain the reasons for declining yields. When yields rise, there will also be a lot of experts, possibly the same ones, fearlessly explaining rising yields with complete certainty.

The one certainty is that October brings an end to the Federal Reserve’s QE 2 bond buying program. While some analysts predicted doom from the end of “quantitative ease”, U.S. economic activity has continued to impress. The U.S. economy expanded at an annualized 4.6% rate in the second quarter of 2014. This obvious economic strength is hard to discount. While we do not forecast markets suffice to say we are closer to a Fed rate hike than we were three months ago.

We suspect even the higher ups at the Fed are uncertain what to do with monetary policy. We believe recently installed Fed Chair Janet Yellen is extremely reticent to tighten monetary policy. That being said, we expect U.S. interest rates will move upward well in advance of any hike by the Bank of Canada. The new Bank of Canada Governor, Mr. Poloz, seems even more reticent to tighten than his monetary neighbour to the south.

What does this mean for yields? To reiterate our view detailed in past newsletters, Canso theorizes “normal” levels of short-term interest rates are inflation plus 1-2%. With inflation of 2% this implies short rates of 3-4%. A positively sloped yield curve implies long rates of 5-6%. With long Canada bond yields at 2.55% at the time of writing, “normal” is a long way away. Even with a flat or 0% inflation rate, bonds are now fully valued in the 2% range.

While politicians and their central banking friends are not keen on tightening monetary policy, it just might be that the market will do some of their work for them. The yield curve tends to “steepen” in advance of a monetary tightening, as investors recognize a stronger economy and potentially rising inflation are on the horizon. As we point out below, we believe the vastly increased sensitivity of bonds to rising yields is not something most bond investors and strategists are ready for.

“When rates rise will credit spreads widen?”

Clients and their advisors ask the question what impact rising yields will have on credit spreads. This question seems almost hypothetical, as government yields have steadily fallen since 1981 and, more recently, since the 2008 Credit Crisis. Conventional wisdom suggests rising rates lead to wider credit spreads but our research suggest otherwise – at least most of the time.

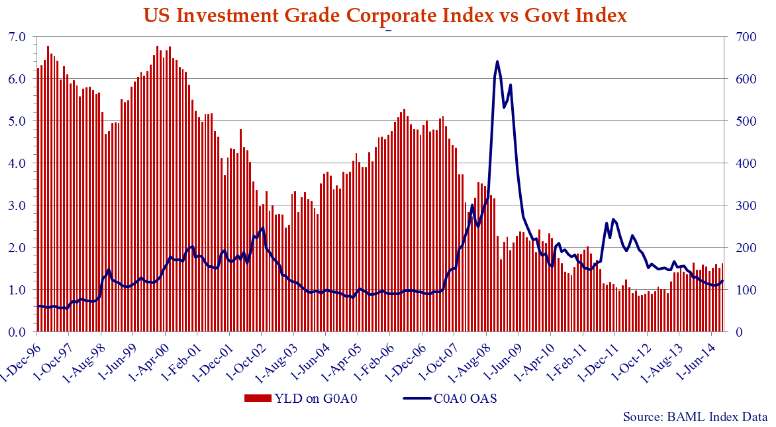

Contrary to consensus, credit spreads generally narrow during periods of rising interest rates and widen in periods of falling yields. Analyzing the U.S. experience over the life of the Bank of America Merrill Lynch U.S. investment grade data series, credit spreads have a negative 0.39 correlation, implying spreads decline when yields increase. While this may be surprising, it makes sense. Rising yields due to monetary policy tightening are a result of economic strengthening. The Fed tightens monetary policy for this reason. When yields fall, it is the result of economic and/or financial market stress which is associated with anticipated corporate weakness causing spreads to widen.

Supporting our conclusion looking at the chart below, we can see the BAML government index yield climbed from 2.52% to 5.28% in the expansionary period from June 2003 to June 2007. The BAML U.S. Investment Grade Corporate Index fell from over 240 bps in late 2002 to just above 100 bps when the Fed began to lower interest rates in 2007. During the four years from June 2003 to June 2007, the corporate yield spread was fairly stable, averaging a spread of +95bps (maximum +123bps/ minimum +81bps).

Looking at corporate spreads during the Credit Crisis, they rose sharply from 129 bps to 641 bps as government yields plunged. The BAML government index yield fell from 4.87% to 1.71% over this period. Our analysis also showed that U.S. high yield spreads exhibit similar patterns as investment grade bonds versus governments.

What about Canada?

The BAML CAD investment grade data (not shown) indicate credit spreads have a negative 0.57 correlation to interest rates over the life of the series. This again implies credit spreads contract with rising rates and widen with falling rates.

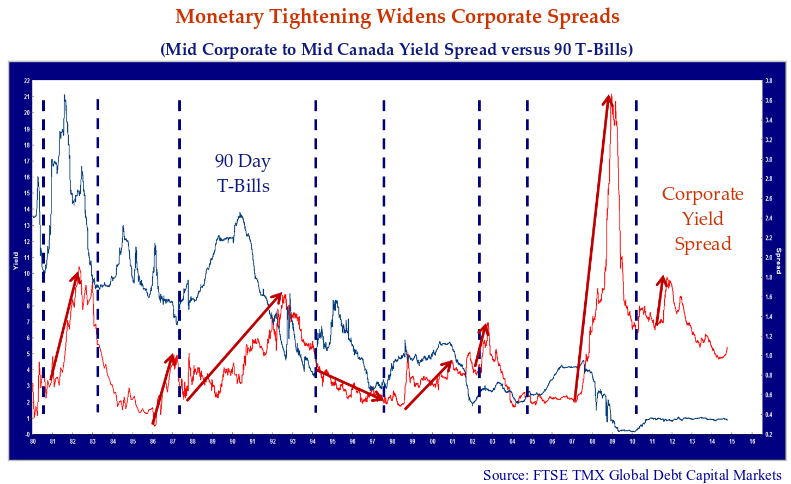

However the Canadian data also show monetary policy tightening can eventually lead to wider yield spreads. In the chart below, we have used the FTSE TMX PC Bond data to calculate the yield spread between the Mid Corporate and Mid Canada bond indices. We plotted this against the 90 Day TBill yield to show periods when monetary policy was tightened and short-term interest rates were rising. The start of a period of rising short-term interest rates is marked with a vertical dashed blue line. The red arrow shows what happened to corporate yield spreads.

Note that when monetary policy is tightened, corporate spreads eventually rise. There has only been one period, from 1994 to 1996, of rising T-Bill yields where corporate spreads fell. Sometimes there is quite a lag, as in 2005 when T-Bill rates increased but the corporate yield spread did not widen until 2007.

Negative correlations between spreads and interest rates seem to refute the conventional wisdom that rising rates lead to wider spreads. At Canso, we believe that rising interest rates do lead to wider spreads, but this is a late cycle phenomenon.

“Credit Notions”

As we have seen in the graph of Canadian corporate spreads and T-Bill yields, higher interest rates due to monetary tightening leads inevitably to wider spreads. This is consistent with the notion of a credit cycle. Loose credit at the start of a cycle leads to a strong economy and eventually to tighter monetary policy. A strong economy is good for credit spreads. Credit metrics improve and defaults fall. As we have shown in past newsletters, default rates are a coincident indicator for credit spreads. Low defaults make for tight credit spreads and higher defaults make for wider spreads.

Easy Leads to Loose?

The “easy money” phase of the cycle leads to “loose credit”, which is what it is meant to accomplish. It then usually leads to speculative financial market activity. This sows the seeds for the final phase of the credit cycle when spreads will widen. Tighter money creates capital scarcity that leads to tight credit conditions, wider spreads and a slower economy. This then precipitates a sell-off in speculative assets.

We expect corporate spreads in Canada could grind tighter but believe that in general, spreads are nearing full value. We note in previous periods that spreads stayed narrow and expensive for long periods of time. It is difficult to predict when spreads will begin to widen and what will precipitate this move.

Enduring Duration

Bonds are sensitive to changes in interest rates. The longer a bond’s term the more sensitive to rate changes. A bond with a duration of 10 years, a measure of sensitivity to yield changes, will move 10% in price for each 1% change in yield. The longer a bonds yield to maturity and the lower its coupon the longer a bond’s duration. All bonds now have a very long duration on a historical basis due to the drop in bond market yields. New issues also have very low coupons which makes their durations even longer.

Canada 30 year bonds have new issue durations of nearly 20 years, compared to 8 to 10 years in the 1990s. The Universe Bond Index duration has also lengthened due to a high weighting in very long term provincial bonds with long durations. Smart provincial treasurers have locked in low interest rates and benefitted their budgets with the result that legions of “Bond Index” and “Closet Index” funds have extended durations.

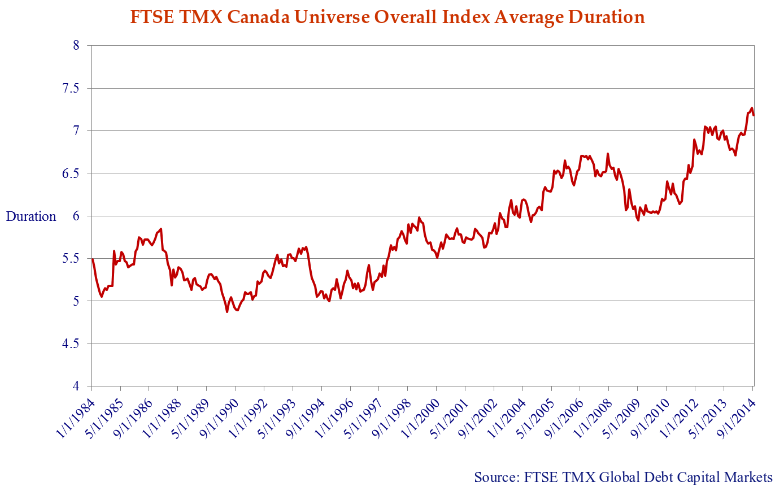

We show the increase in the duration of the FTSE TMX Bond Universe Index in the chart below. It has increased almost two years from 5.5 in 2002 to the present 7.3 years.

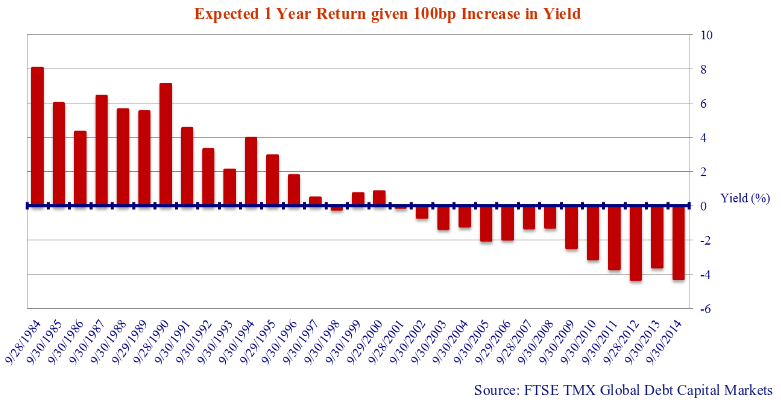

This might not be good for bond portfolios going forward. In the chart below we calculate the hypothetical expected return for the one year after a 1% rise in the Bond Universe yield. In 1994, just before the bond market swooned during a Greenspan Fed tightening period, the one-year return after a 1% increase would have been 2%, given the duration and yield of the Universe Index at the time. Since rates actually rose 2.5%, the actual one-year return ending December 31, 1994 was -4.3%. Twenty years later, falling yields, falling coupons and rising duration mean that it would take just a 1% increase in yields for the same -4% return.

“Wasn’t That a Party?”

The Irish Rovers sang that it “could have been the six pack, might have been the gin” in their classic 1980 post party recovery song. While self-induced hangovers typically pass within a day or two (three or four if you’ve ever attended the Grey Cup) we suspect the hangover from the high yield markets multi-year binge could be substantially longer.

We have written extensively about the unholy alliance of underwriters, private equity sponsors and portfolio managers who created the investment channel that sells really poor credit to unsuspecting retail investors holding bank loan mutual funds and ETFs. We’ve also pointed out the pitfalls of “covenant light” deal structures and the incurable “madness” of the US high yield and leveraged loan markets in previous Corporate Bond Letters. We at first counselled caution and then outright avoidance of these “snake oil” securities peddled by bonus-crazed bankers. These will almost certainly “snake bite” investors in the not too distant future. A quote from the Financial Times captured the essence of the leveraged loan market over the last few years:

“Deals ‘were structured and underwritten for a bull market’, said Mr Cohen [Head of Loan Capital Markets at Credit Suisse]. Some had terms in them that investors found ‘reprehensible, but they needed the paper.’” Financial Times, October 27, 2014. Tracy Alloway in New York.

We caught a glimpse of the potential carnage ahead in September when the Merrill Lynch High Yield Index spread widened to 440 bps at September 30th, up from a 12-month low of 353 bps at the end of June. This knocked 3-5% off the price of most high yield bonds and leveraged bank loans. The underwriters of course declined to purchase their “used” wares. Happy to sell their new issues, dealers weren’t keen on investing their own capital in their dodgy credit creations. The savviest amongst them likely went short to protect their inventories. This added to the selling pressure.

This spread widening prompted many market “cheerleaders” to declare the high yield market “cheap” and wider levels a terrific buying opportunity. We do not see this modest pullback as a “buying” opportunity. The market cheerleaders usually receive a large part of their compensation for convincing people to buy. Deal structures and pricing still heavily favour borrowers over lenders. We note the current index spread is still tight versus the historic average of 585bps and a far cry from the maximum of 1988 reached in 2008. Until the market demands and can extract reasonable terms from underwriters and borrowers we at Canso prefer to watch from the sidelines. We would rather leave the party early than stick around and watch the house get trashed.

Loonie Tunes

At Canso we spend our days in the unglamorous study of financial statements and trust indentures. As fundamental bottom up portfolio managers, we try to determine what can go wrong in a world where everyone assures us things are “just right!” We look with some bewilderment at the large group of economists and strategists who assuredly predict markets but seldom get things right.

Canso’s “Spidey Sense” was tingling in July of 2013 after we completed our thorough review of the Canadian housing market (see Canso Px The Canadian Housing Market July 2013). Based on our view that Canadian housing prices were overvalued and the Canadian economy was running ahead of itself, we felt the odds were stacked against the Canadian dollar (CAD). It has come off considerably since then, and we think the damage is not over.

As with all financial markets one can never be sure what the trigger points are for major moves. We discovered a strong correlation of 0.85 between CAD movements and the price of oil as measured by West Texas Intermediate (WTI). It would seem as goes the price of oil so goes the CAD dollar. We suspect that if we can do these calculations others can too. With the US on the verge of energy selfsufficiency and evidence of high production in the Middle East this does not bode well for the price of oil and the CAD. We think the CAD has further to fall.

Our mid-2013 unscientific assessment pegged a reasonable CAD/USD exchange rate at $0.80 U.S. We note that since 1991 the average exchange rate is a not too distant $0.81. Rising U.S. interest rates and more importantly falling oil prices will probably push the CAD down considerably from current levels.

Take the Money and Run

Sponsors of ETF’s and CLO’s trumpet the advantages of low fees, diversification and daily liquidity. The issue of liquidity is becoming more and more topical and regulators are increasingly weighing the prospects that a run on ETF’s or CLO’s could precipitate another “yet to be named” crisis.

We’ve highlighted the dangers posed by the archaic settlement processes in the bank loan market where trades can often take weeks or often months to settle. A run on a bank loan fund would not be much fun. Taking the money and running might be easier said than done. The much-publicized redemption of US$23 billion from PIMCO’s Total Return Fund following the departure of Bill Gross highlights how quickly a seemingly normal situation can morph into a near panic.

Measure Twice, Cut Once

Norm Abram, the Master Carpenter of the PBS home improvement show, This Old House, toiled away on PBS long before HGTV was even a concept. He wrote an excellent “do-it-yourself” carpentry book entitled Measure Twice Cut Once. Mr. Abram was the Mike Holmes of his era, sans earring and sermonizing.

Norms’ motto “measure twice cut once” is his way of life. We at Canso share Norm’s conviction that it is better to prepare before you take action to ensure things are done correctly the first time. Our Canso investment process relies on knowledge, experience, teamwork and, particularly, patience. Nevertheless sometimes, in spite of our best efforts, we make mistakes. Even a Master Carpenter makes an errant cut or bends a nail once in a while. We were reminded of our own fallibility in September when we received the final distribution on the bankrupt Teleglobe bonds that we still held in one account.

A “Telling” Credit Collapse

Teleglobe Canada Inc. was a once a Canadian high flying and global telecommunications company. Originally a Crown corporation which handled the long distance telephone traffic over oceanic cables, it was privatized in the 1980s. BCE Inc. purchased the 80% of the company it did not own in November 2000 for $7.4 billion. Teleglobe also had $4.6 billion in public bonds which once had a “high quality” or A credit rating, based on the BCE ownership and the pronounced “importance” of Teleglobe to BCE. We had passed on these issues as investment grade bonds as BCE did not explicitly guarantee these securities and we struggled to understand Teleglobe’s business plan. This was during the dot.com mania where investors were chasing opportunity and ignoring the risks.

When the dot.com and telecom boom went bust in 2000, Teleglobe struggled. We bought a small position as a distressed credit at $55, already well down from its $100 par value. BCE wrote-off its investment in April 2002 and Teleglobe filed for court protection in May of the same year, less than two years after BCE purchased it!

Although we thought the significant discount on our investment to the book value of the Teleglobe assets provided us with substantial upside, we spent a lot of effort on determining the “recovery value” for our Maximum Loss estimate. There were very few cash flows from the new network but the book value of the assets exceeded $8 billion. We came up with a range of $15-25, which implied more than a 50% Maximum Loss from our purchase level.

The actual recovery was extremely low, our worst Canso drubbing of all time. The Teleglobe assets with a book value of over $8 billion were sold for a mere $125 million. Canso’s recovery for bonds issued at $100 and purchased at $55 was $4.60 recovered over the 12 years since 2002. Without accounting for the time value of money, $4.60 on a $55 investment represents a meagre 8% recovery. Although purchased at a distressed level, this more than 90% loss was certainly not Canso’s finest hour and was far below our worst case estimate.

We highlight Teleglobe to demonstrate we do make mistakes. However importantly, each investment experience at Canso adds to the collective knowledge of our firm and increases the likelihood that these mistakes will not be repeated. The real value of Teleglobe was the lesson we learned on the value of assets with limited cash flows. Lots of potential and promise does not make up for lack of revenues. This experience also reinforces the benefits of our maximum loss methodology that properly sized the Teleglobe position for the risk we were taking. Although we lost most of our investment, it was sized appropriately given the value added requirement of the portfolios for which it was purchased.

“Reflections”

The Supremes sang in their 1967 hit record of being “Trapped in a world that’s a distorted reality”. We sympathize with the Motown legends as Canso reflects on current events and on market cycles gone by. We cannot help but notice the current distortions across the global financial markets and wonder at those who argue once again, “this time is different”.

Historically low interest rates, cavalier lending standards and general investor complacency will not last forever. We acknowledge these extremes can last for extended periods of time but also note that when corrections occur they are often violent and irrational. The financial markets behavior over many of October’s trading sessions may portend more severe movements to come but we are not sure it is time to “cue the bugles” just yet.

Credit markets are slowly and inevitably moving towards another extreme in valuation. Right now, Canadian corporate bond spreads are near their historical average, but may be more expensive than appearances suggest. We believe the increased percentage of BBB credits in the investment grade indices makes for a higher corporate yield spread than in years gone by.

Our bottom up research and valuation discipline tends to move our portfolios towards higher quality as the credit cycle matures. We are increasingly finding higher quality bonds better risk-adjusted value than their lower quality peers.

We were very conservatively positioned in our portfolios in 2007, heading into the Credit Crisis. This happened very slowly over two or three years starting in 2004. The Euro Debt Crisis found us more fully invested, but most of our holdings were quite cheap, even though many of them had narrowed considerably.

Golden Goldman

A good example of our shifting portfolio would be the Goldman Sachs 2016 Maple bonds. By 2006, many foreign financial issuers had taken advantage of the strong demand for yield in the Canadian bond market. In 2006 Goldman Sachs issued 5.25% 2016 senior bonds at a spread of 78bps. Canso passed on this issue as we believed we were in a financial mania, which turned out to be very prescient.

In the midst of the Credit Crisis Canso established major positions in these bonds at spreads as high as 800 bps. These bonds then narrowed to 180 bps in 2011 before widening to 400 bps during the Euro Debt Crisis. We didn’t sell, and opportunistically bought more bonds during this period. We have been recently selling these bonds at spreads versus Canada’s of 80 bps. From our point of view, holding A rated bonds at 80 bps compared to NHA MBS at 55 bps doesn’t make sense. We could pick up another 25 bps in yield spread in the Goldman bonds, but we think the AAA rated NHA MBA represent better credit value and liquidity.

You might accuse us of wanting to be “safe rather than sorry” but in this case perhaps “measure the spread twice and cut once” might be more apt!