A Marvin Moment??

“What’s Going On” was the plaintive refrain and title of Marvin Gaye’s 1971 hit song about the controversial Vietnam War and the resulting societal and political upset in the United States. His song of confusion and disappointment seems as relevant to us today. We look with trepidation on the political and social tumult around the world and wonder ourselves what is going on.

There are savage wars in Ukraine and Gaza. The Western political and financial system that has kept things orderly since WW2 is under increasing threat and now seems ready to blow up in the face of internal political stresses in most Western democracies. In the UK, the ruling Conservatives have suffered a historic election wipeout and left-wing Labour is in power for the first time in many years. In other Western democracies there is a rise in conservative right-wing and anti-immigration parties that is re-ordering their politics.

Straining and Draining Politics

Things seem destined to overturn the ruling parties in the not-too-distant future. Macron’s snap election in France looks like it sidelined the right-wing National Rally of Marie Le Pen but a Leftist Coalition got the most votes. This relegated Macron’s centrist party to a minority in the National Assembly and France to fractious coalition government. Even boring Canada is looking like the ruling Liberals are on their way out, after a by-election defeat in a formerly safe Toronto riding. Canada seems united in its feeling that the Trudeau government has passed its Best Before date.

The U.S. also seems to be melting down from the strains on the American judicial and political system from the Biden/Trump presidential rematch. With 4 months to go, we wonder how the situation could get worse after the recent Presidential Debate and the Supreme Court decision on presidential immunity, but it very much could.

Political Ignorance is Financial Bliss

We are especially concerned that the financial markets are still dancing to the continuation of their own tune “Up, Up and Away” in their beautiful market balloon. Investors are still assuming risk with abandon while things seem to be melting down politically. We don’t try to time markets, but we value securities using risk and return. Politics can’t really be predicted in its effects on valuations, but unfortunately the financial markets seem even less rational than our politics. Economic and political risk is clearly growing but the ebullience of investors has valuations at very expensive levels. Things are literally priced for perfection, despite still being at the highest interest rates in many years. Markets seem not just confused but in denial that anything could go wrong. They still expect their friendly central banks to rescue them from their financial foibles if anything actually does go wrong.

Investor Confusion and Delusion

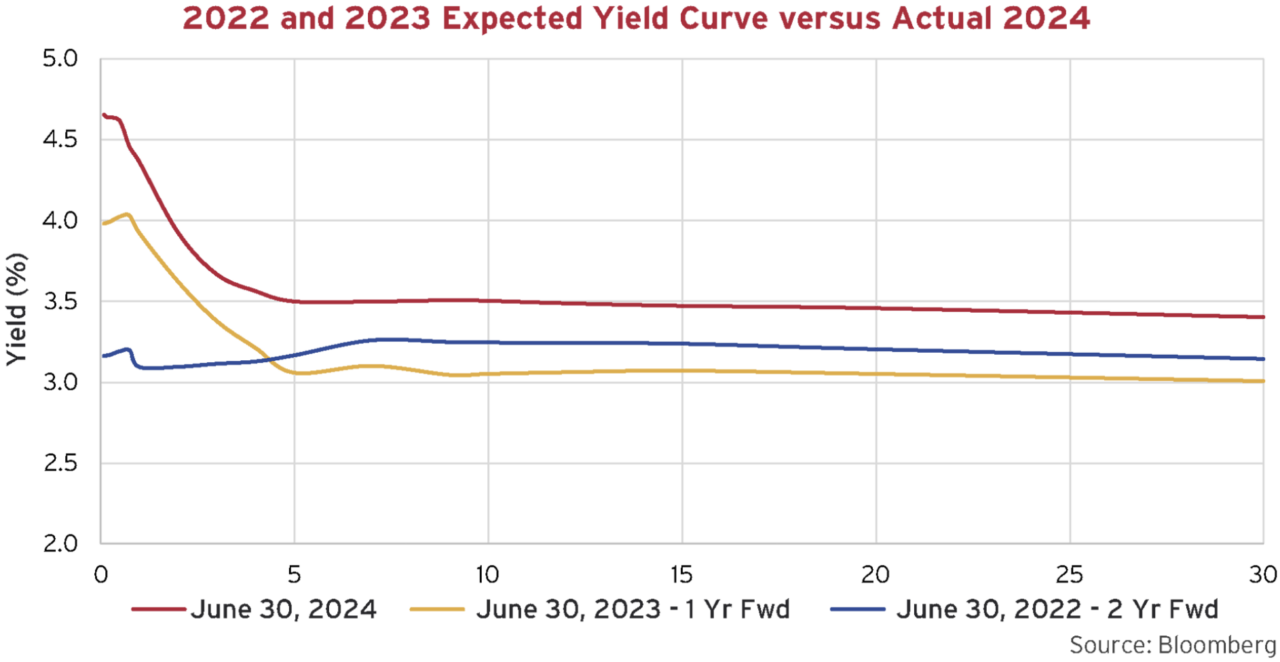

We’re also in a very confused state about the economy. The financial experts, central banks and investor consensus have been very wrong about the economy and monetary policy. Interest rates are higher than the market expected as monetary policy stays tight to fight sticky inflation. Interest rate expectations and forecasted yield curves below tell the tale of market confusion and perhaps even delusion. As we have told you many times on these pages, most economists and financial market “experts” have predicted recession since the yield curve inverted in 2022. That recession has not happened, at least until now, but then surprises are never predicted and tend to confound the consensus.

Dotty Plotting

Consumer spending powers a modern economy and consumers have continued to spend even though interest rates have soared. This defied the conventional economic wisdom that higher interest rates would quickly put the Western economies into recession. Indeed, interest rates have proven to be a very blunt weapon in defiance of the “fine tuning” of the Federal Reserve and other central banks to get inflation back to its targeted 2% levels. The impotency of higher interest rates to stem inflation has confounded the experts. Even the U.S. Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) that sets U.S. interest rates has been way off in its predictions. In retrospect, the FOMC “Dot Plot” predictions of future interest rates have been no better than random and have stoked investor confusion.

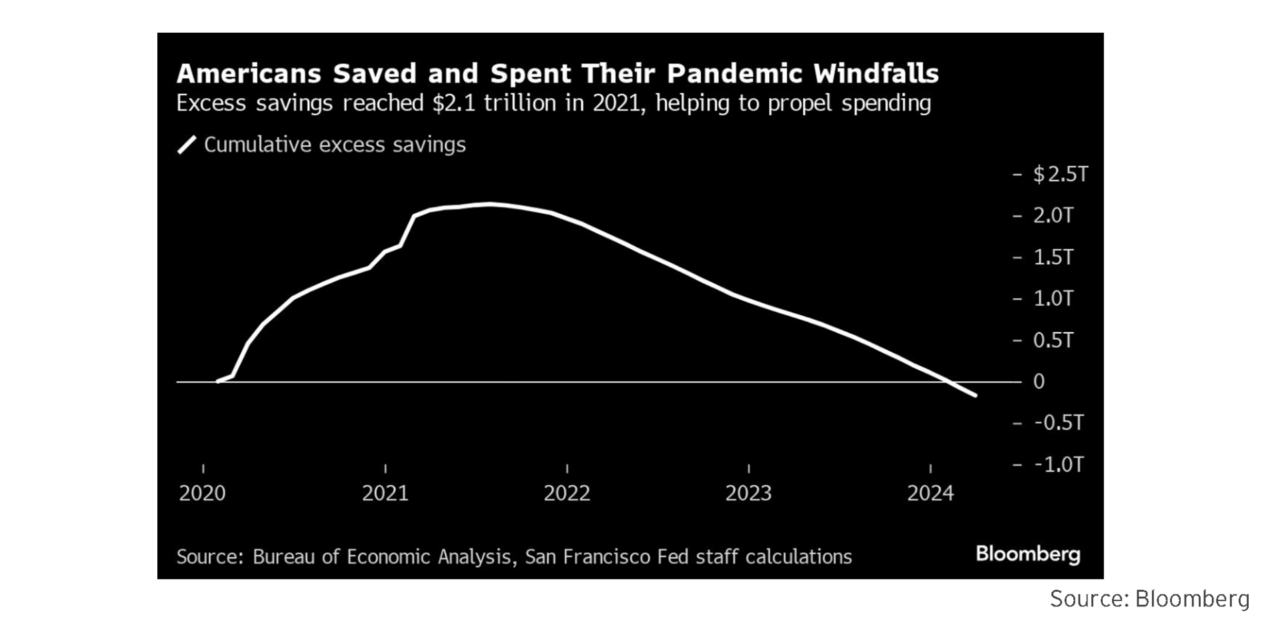

We have warned continually that so much money was created during the Pandemic Panic by governments that it would be very hard to get things back under control. That “free money” was saved by consumers, and they couldn’t spend it fully during the pandemic. That consumer cash reserve has powered the continued strength of the economy. Now that the market consensus is united in its belief that we have arrived at the nirvana of an economic soft landing, we’re starting to get worried that economic weakness and even recession might be a distinct possibility.

Shop Until GDP Drops?

The chart below from Bloomberg shows how the spending power accumulated during the pandemic might finally be running out. The accompanying article points out that higher rates are biting, just not equally:

“Consumers might be continuing to spend, but it’s taking a toll,” said Tim Quinlan, a senior economist at Wells Fargo & Co… “The cost of carrying that debt is taking a bite out of people’s incomes in a way that it has not since the financial crisis,” Quinlan said.”1

This statistical calculation of savings doesn’t include increases in wealth. Higher interest rates don’t affect consumers with low fixed rate mortgages they renewed during the pandemic and growing home equity and investment portfolios. Higher interest income and portfolio values have been a windfall for many older consumers saving for retirement.

“In fact, some Americans have seen their wealth grow substantially thanks to a surge in home values in recent years and record-high stock prices. Continued spending by these individuals could bolster consumer outlays in the aggregate, even if others are forced to dial back spending…. “We just about doubled our retirement from before the pandemic,” said Geoff Olson, a 64-year-old robotics engineer who lives in California’s Bay Area. “That was a combination of us putting in more money, and we just did really well in the stock market.””1

The Bond and Stock Markets Disagree

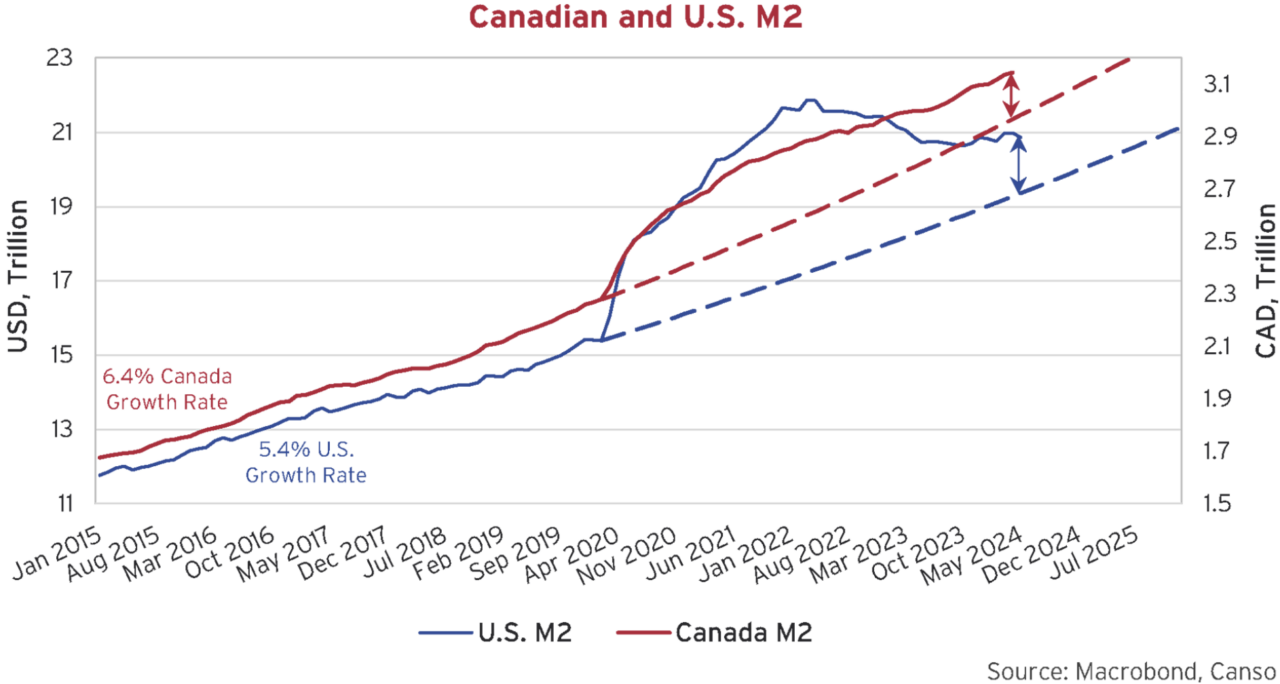

The inverted yield curve has had the bond market predicting recession, falling inflation and interest rates for some time. The stock market disagreed, predicting their good times would continue to roll on, with rallies to new highs at any glimmer of easing monetary policy and lower interest rates. Both the stock and bond market want lower interest rates, just like consumers and the housing markets. For us, given our belief that “money still matters”, the real question is how much money is still out there to be spent? Interest rates are definitely biting and economies slowing, but the excess money supply created during the pandemic still remains.

Unprecedented and Huge Stimulus

We’ve updated our graph below on U.S. (blue line) and Canadian (red line) M2 that suggests to us that there’s still quite a bit of money out there. For those readers who haven’t seen this graph before, we have plotted U.S. and Canadian M2, the most common measure of money supply. You can see the very obvious unprecedented and huge increases in M2 during the pandemic. We have calculated the pre-pandemic growth rates in Canadian M2 at 6.4% and U.S. M2 at 5.4%. We have also extended these growth rates as the dashed lines.

The BOC move to hold interest rates and recently lower them has current M2 growing similarly to the 6.4% extended line, albeit with an extra $200 billion still sloshing around the Canadian financial system. The U.S. M2 rose to a peak of almost $22 trillion in March 2022, up almost $7 trillion from just over $15 trillion in January 2020. U.S. M2 actually shrunk from its peak by almost $1 trillion, as the Fed raised interest rates. The Fed actually had to start expanding M2 again to hold interest rates at the current Fed Funds target of 5.5%. It looks to us that the U.S. now has almost an extra $1.5 trillion in M2 compared to the extended pre-pandemic trend.

Schloss Moneyhof

Our archaic devotion to money supply seems quaint in these days of Modern Monetary Policy when most economists and central bankers don’t believe that money matters any more. Money does matter, but nobody including us knows exactly how much it matters. Our lonely belief (read our 2020-2022 Market Observers) was that the stupendous amounts of money created during the pandemic would cause an inflationary problem and we were right. The experts and markets then believed that the “massive” increases in interest rates would very quickly stop the economy dead in its tracks and inflation would summarily be defeated. They were wrong. While coming off zero interest rates were a shock, those higher rates weren’t historically very high at all compared to inflation. To us, if there was enough money still sloshing around the financial system, people could spend it. Lenders still had money to lend, and employers could give wage increases, providing the money that consumers needed to continue their spending ways.

The Monetary Gods Flail at Inflation

The current market consensus stems from an almost mystical belief in the ability of central banks to “Command and Control” their economies. No war ever goes as predicted by the generals who fought in the last one, and the Fed’s and other central banks’ “War on Inflation” is no different. Used to the glory and fame of fighting financial crises, central banks thought their interest rate tactics were perfected. The combined fiscal and monetary stimulus of the Covid Pandemic put paid to that idea. The transitory “supply chain” inflation that was supposed to go away without tight monetary policy soon became the highest inflation in 40 years. As a result, we had the tightest monetary policy and highest interest rates in 40 years!

The Bond Market Fails at Forecasting

You are probably now railing at our challenge to the conventional model of the economy and financial markets. There is some proof in our analytical pudding. You have also often heard that the bond market has “forecasted” interest rates. Every time a central bank meets, we hear with much anticipation that the yield curve “predicts” several reductions in interest rates. The actual predicted yield curves below should tell you how badly the market forecasts interest rates.

The current yield curve is shown below in red at June 30, 2024. Interest rates are much higher than the bond market predicted in both 2022 and 2023.

Two years ago, at the end of June 2022, the market predicted the blue line for interest rates on June 30, 2024. That was wrong by about 0.25% low for bond terms longer than 7 years but more wrong for shorter terms. The bond market consensus thought the BOC rate would be 3.1% when it is actually 4.75%, a massive 1.7% difference!! The forecast just a year ago in June 2023 was more wrong for terms longer than 5 years, predicting rates 0.5% lower, but less wrong for the BOC rate, which it predicted at “only” 0.7% lower. In summary, the bond market is a terrible predictor of interest rates, largely because it is the summary opinions of frail humans. Clearly the consensus expected higher short-term rates to bite more quickly and longer-term rates to fall as the economy weakened into recession.

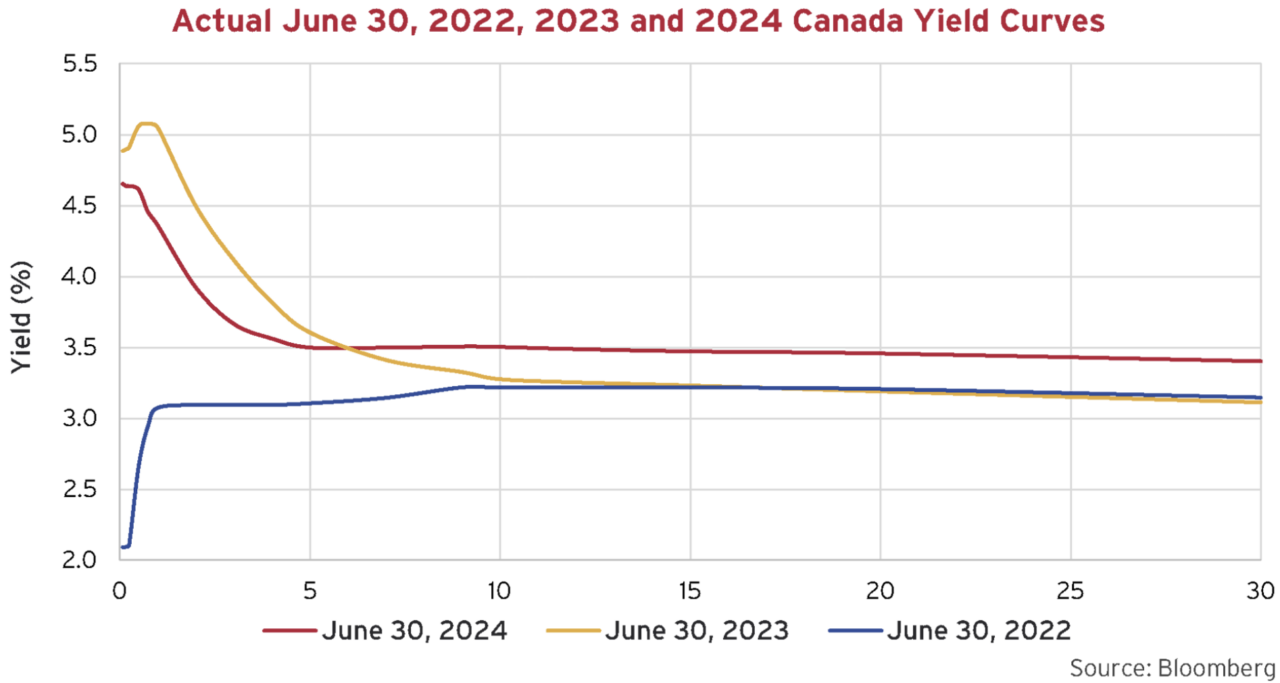

Longer Yields Up

It is fascinating to look retrospectively at the current Canadian bond yield curve versus those in June 2022 and 2023. The 2022 and 2023 yields were the same for terms longer than 10 years but today’s yields in red are 0.3% higher. The 2022 yield curve was “normal” with the BOC rate at 1.75% and long-term yields higher at 3.2%. The 2023 yield curve was more inverted than at present, with short rates above 5%, compared to today’s 4.75%.

Yields moved up 0.3% from 2022 and 2023 for bonds longer than 10 years in term. This could mean, as we expected, that the Canadian bond market is finally coming to a grim realization that the happy days of Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP) are well behind us.

Recent But Not Decent Forecasts

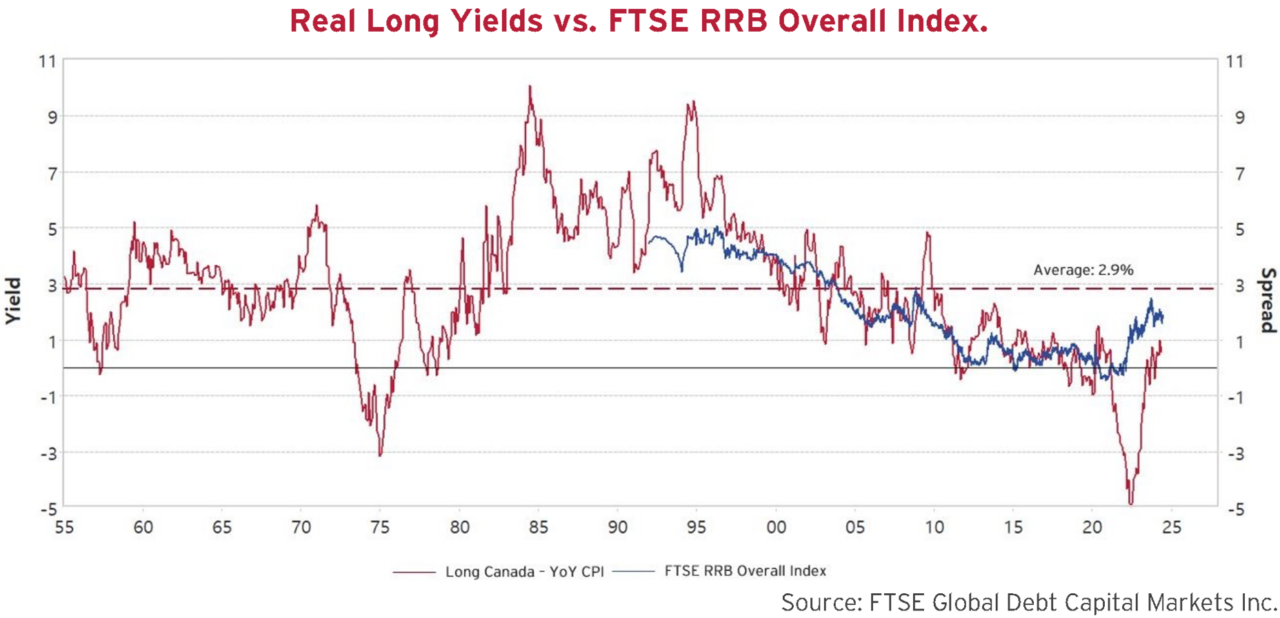

Economists, bond portfolio managers and market strategists tend to suffer from the psychological affliction of “recency”. This means their recent past is weighted much more than the seemingly distant sands of time only a few decades ago. The chart below shows this. We’ve taken the real yield (yield minus YoY CPI) on the Canadian long bond from 1955 to present and averaged it. That shows the average real yield on the Canadian long bond at just under 3%. The 20 year period from 1955-1975 was close to this, and the inflationary period from 1973-1981 saw very negative real yields. This was followed by very high yields above 5% until the early 2000s as investors worried about a return of the inflationary period. Since then, it was a one way drop to zero during the lax monetary policy of the ZIRP period from 2011 to 2021. Interested readers can see more of this analysis in our September 2022 Canso Position Report entitled “W(h)ither Inflation and Bond Yields – September 2022.”

We have also plotted the yield on the Canadian Real Return Bond Index, which shows how the real yield on RRBs went to below zero during the ZIRP craziness.

The problem with that period is that it engendered a belief that interest rates should be zero and even negative. At the time, the financial chattering class trumpeted even negative nominal interest rates. It seemed crazy to us at the time that investors would pay issuers for the pleasure of investing in their debt, but many “experts” promoted the idea of negative interest rates.

Breaking Inflation Psychosis

The problem now is that current Canadian long bond yields at 3.5% would be a real yield of 1.5% at 2% inflation, which is low by historical standards, excepting the period of ZIRP madness. This is confirmed by the Break Even Spread (BES) or market estimate of inflation on long Canadian RRBs that currently predicts 1.9% inflation. If inflation ends up a little higher, then we expect long term yields to rise. This might happen even if short yields fall with looser monetary policy in response to economic weakness. We note the Fed’s latest minutes suggest that economic weakness might reduce its inflation-fighting resolve and have it ease monetary policy. The Bank of Canada seems even more disposed to ease, even if inflation stays higher than target. That suggests to us that the yield curve could steepen dramatically as short-term rates are administered downwards and long-term rates respond to the resulting increased inflation risks. This would very much catch the bond market offside.

Slower but not Lower

We now believe that higher interest rates are slowing economic activity, as the drop in inflation has increased real interest rates. In the U.S. and Canada, with the CPI under 3%, we now have positive real short-term interest rates of almost 2%. This has definitely ended the glorious days of “free money”, but fiscal policy on the other hand is still very loose.

Governments around the world are still running deficits and the recent and upcoming elections won’t change that any time soon. If there is a second Trump Administration after the U.S. elections in November, it looks like tax cuts and deficit spending will be even larger than the last time around.

“Debt is not free anymore”

We note that a hallmark of strongman and/or populist governments is debt monetization. It is easier for voters to stomach higher indirect taxes and deficit spending via inflation than actually paying higher taxes. A CNN article hews to our view that government debt monetization has caused a significant change to the prospects for the global bond markets:

“Governments owe an unprecedented $91 trillion, an amount almost equal to the size of the global economy and one that will ultimately exact a heavy toll on their populations. Debt burdens have grown so large — in part because of the cost of the pandemic — that they now pose a growing threat to living standards even in rich economies, including the United States.

Yet, in a year of elections around the world, politicians are largely ignoring the problem, unwilling to level with voters about the tax increases and spending cuts needed to tackle the deluge of borrowing. In some cases, they’re even making profligate promises that could at the very least jack up inflation again and could even trigger a new financial crisis.”2

Our previously extreme views on ZIRP and debt monetization during the pandemic are now being echoed by Ivy League professors:

“Kenneth Rogoff, an economics professor at Harvard University, agrees that the US and other countries will have to make painful adjustments. Debt is “not free anymore,” he told CNN.

“In the 2010s, a lot of academics, policymakers and central bankers came to the view that interest rates were just going to be near zero forever and then they started thinking debt was a free lunch,” he said. “That was always wrong-headed because you can think of government debt as holding a flexible-rate mortgage and, if the interest rates go up sharply, your interest payments go up a lot. And that’s exactly what’s happened all over the world.””2

All this suggests to us that our belief in a steeper yield curve is well founded. We very well could have sticky inflation higher than the 2% target and the prospect of higher deficit spending combining to lift longer-term bond yields while monetary policy easing lowers short-term yields. It also suggests to us that inflation-linked bonds are still attractive.

A Looming Private Credit Disaster??

We are increasingly worried about the effect of rising interest rates on levered issuers, particularly those companies loaded up with debt by their Private Equity (PE) sponsors. Some of us at Canso have been credit portfolio managers for 40 years, among the most experienced credit people still active, as the Toronto CFA Society pointed out in their recent profile of our John Carswell. To be frank, we’ve never seen a market with weaker lending standards than the current “Private Debt” mania. It is easy to lend money, but it often becomes very hard to get it back. We think we are now entering that part of the credit cycle where loan losses will soar.

Beware of the Private Debt Mania

The current private debt mania stems from the rush of investors who were anxious to join the yield gravy train on “private debt” when interest rates were zero. As always in the investment markets, the salespeople noticed the “high yields” and rushed to offer them to their clients. It started with supposedly sophisticated investors like public sector pension funds and wealthy families but has now morphed into a retail investment product. You can promise a high interest rate or yield, but your eventual return depends on what you get back.

The Problem is Getting Your Money Back

The problem is that those “lending” the money aren’t really lending their own money. A recent study by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) found that 40% of private credit funds don’t have any of their own money in their funds:

“Watchdogs are concerned about the “substantial” risk to investors in the private credit market after it emerged that almost 40% of funds don’t have skin in the game. The decision by so many managers to avoid putting their own capital into the vehicles creates an “incentive misalignment,” the Bank of International Settlements said this week. The risk is that industry players could prioritize their profit over investors’ return.”3

BISguided PhDs

Since the BIS also estimates that private credit has grown to a $2.1 trillion industry, they now worry that it puts the global financial system at risk since interest rates have risen substantially. Let’s see, the central bank geniuses who regulate the global financial system and lowered interest rates to zero for a decade now worry about the number of investors seeking yield who pumped up the private debt markets.

Who could possibly know that zero yields would encourage a “stretch for yield” and risk taking? That thought did not seem to have occurred to the thousands of very smart central bank staff and researchers with PhDs until now. We’ve been telling you in our own less educated but more experienced ways that it seemed to us that most private debt issues financed levered PE transactions. BIS also confirmed that, estimating that 78% of private debt issues financed PE deals. Even more interesting is the BIS observation that only 40% of private debt managers use third party pricing. The 60% who don’t are probably keeping prices and therefore their fees and bonuses high. That’s quite an incentive for sponsors to ignore the negatives. It also causes less “volatility” than the bad old public markets, a perverse advantage lauded by the many private market enthusiasts at Canadian public sector pension funds.

Bonfire of the Credit Inanities

Bloomberg recently interviewed Wayne Dahl of Oaktree on private credit:

“More stress will emerge in private credit, though the path of interest rates will be critical, Wayne Dahl, co-portfolio manager for Oaktree’s global credit and investment grade solutions strategies, said on Bloomberg’s Credit Edge podcast. “There’s just a lot of uncertainty that we’re going to see in the private credit market,” he said. “It’s difficult to always get that full picture of exactly what’s going on.””3

We agree with Mr. Dahl of Oaktree that it is difficult to know what is going on in the private credit markets. The obvious self-interest and opaqueness of the private credit industry suggests to us that the BIS’s “incentive misalignment” is a gross understatement. We would suggest a description of the current private credit markets such as an “opaque cesspool of lousy loans to some of the greediest and self-interested people in the world”. Then again, we have never been accused of being investment politicians who seek favour and higher bonuses by agreeing with consensus thought.

Structured Rupture

Since the PE sponsors are probably more mercenary and self-interested than their Private Debt colleagues, the restructurings to come will be absolutely brutal. Despite the best efforts of regulators after the Credit Crisis to restrict rote investment in structured products, many of the private debt issues have gone into Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) and Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs). As we said in the lead up to the Credit Crisis in 2008, these credit abominations slice and dice very sketchy loans into “tranches” of varying credit quality.

Lacking Statistical Sense

The problem in the 2008 Credit Crisis was that the credit ratings assumed very important default and recovery statistics on sub-prime mortgage performance that turned out to be very wrong. Underwriters gamed the ratings for hefty origination fees and literally lent money without a chance of recovery to very weak borrowers. This time around it seems that the PE sponsors have done the same thing, albeit with sub-prime companies. Easy money at literally zero interest rates meant that valuations of companies soared, and PE sponsors paid what they had to invest in these sub-prime companies. Those new entrants wanting in on the hot PE bonanza had to buy at higher and higher prices. Those high prices often meant that PE sponsored companies were trading at higher prices than public market equivalents, so the only “exits” were private sales, largely to another PE firm.

Shrinking CLO Values

Now there are few buyers and many levered companies. The only refuge from the much higher interest burdens is either bankruptcy or “Liability Management Exercises” (LMEs). Most of these see a group of creditors taking superior security to existing creditors due to flaws in the drafting of the loan and credit agreements. These flaws allow PE sponsors to take whatever attractive security they now have and offer it in exchange for new funding.

A recent research piece by the CLO team at BofA points out that the creditors left behind, usually the passive CLO holders, are seriously disadvantaged by such trends. They found that 60% of LMEs eventually default within 4 years and that the investors who didn’t participate had very low recoveries on their so-called “senior secured loans”, in some cases even less than 5%. Clearly, CLO deals rated on the very high normal recoveries for senior secured loans are not going to do very well.

Massive Investment Idiocy

We are now in the deterioration phase of the credit cycle. Easy money and credit inflates asset values and always ends up with poor lending and investment decision making. We continue to believe that this credit cycle is not going to be a short one with a sharp recovery. The 10 years of ZIRP madness from 2011 to 2021 and the post-pandemic Investment Bubble distorted the financial markets so much that it is going to take a long time to recover. The huge monetary stimulus of the pandemic markets caused investment idiocy on a massive scale, and we are only now finding out how bad things are as the monetary tsunami flows out the other way. That makes us loathe to take risk without proper compensation, so we are very much in our capital preservation mode and that leaves us with an increasingly cautious portfolio positioning.