Adamantly Wrong

Early in 2023, the economic forecasters and market sages were adamant in their New Year forecasts that it would be a year of recession and disappointing financial markets. Interest rates and inflation had been the highest in many years during 2022 and absolutely no one forecasted anything hopeful for 2023. The consensus was down markets for equities and higher yields for bonds in the face of stubbornly high inflation.

As financial markets are wont to do, they then defied the conventional wisdom and soared, handing equities and most risk assets substantial gains. Bonds did fine as well, as inflation came off its peak and yields fell hard in the fourth quarter as investors anticipated their dream state “Soft Landing”. All in all, those who are supposed to know what is going on didn’t have a clue. That’s why we don’t forecast economics or markets at Canso and instead concentrate on the valuation of the securities in our portfolios.

Enjoying Higher Prices

By year end 2023, investors were jubilant at their good fortune and that has continued into 2024. The so-called experts who called for dismal markets in 2023 were nowhere to be found in the 2024 New Year prognostications. Happy days were here again, and nobody wanted to spoil the fortunes from soaring markets that had been handed to investors by saying anything remotely negative this time around.

That optimism was warranted as the first quarter 2024 ended up for the stock markets, with 10% returns for most major equity indices. Good news for the economy was bad news for bonds. Their returns were flat to negative, as their now higher yields failed to compensate for their drop in price as bond yields rose on decent economic news. The consensus market forecast was for central banks easing monetary policy and lowering rates. That got pushed out farther and farther as things looked less and less dire for the economy and yields ratcheted up accordingly.

Wary of the Unexpected

Our view has not changed much in the past three months. We think the monetary stimulation during the pandemic still has the potential to keep inflation higher than many think. Most current portfolio managers cannot fathom a decent economy with “above target” inflation and high interest rates, but that was the case many times before the Credit and Euro Debt Crises. Those engendered the Zero Interest Rate Policies (ZIRP) of the foolish central bankers who came to believe money didn’t matter. In terms of our boring valuation discipline, things are currently looking stretched to us. There’s nary a thought of market setbacks and/or a weak economy in the financial media. That has got us worried. Mr. Market has a way of doing the unexpected, and with everyone enjoying the higher price and return ride they’re on, we continue to sell into the strong bids that we see for things we bought cheaply when nobody wanted to own them during the pandemic. When something doesn’t compensate us with a high enough return for its risk, our valuation discipline tells us to sell.

Punitive and Bizarre

The current level of interest rates is thought to be punitive and even bizarre by today’s average investor and economist, but things trundled along economically very well in past periods with interest rates at even higher levels than we are now experiencing. The default position of the bond market seems to be that we will eventually get back to the zero interest rate La La Land of ZIRP. This anticipation manifests in an inverted yield curve, where short term administered rates are being held up by central banks and bond investors are happy to lock in their money for longer terms at lower rates. Perversely, now that nobody is concerned about a recession due to the dreaded yield curve inversion (that we’ve now had for 3 years!!), we think there is a very good chance that we will eventually get economic weakness, especially in the residential housing addicted Canadian economy.

Creepy Yields

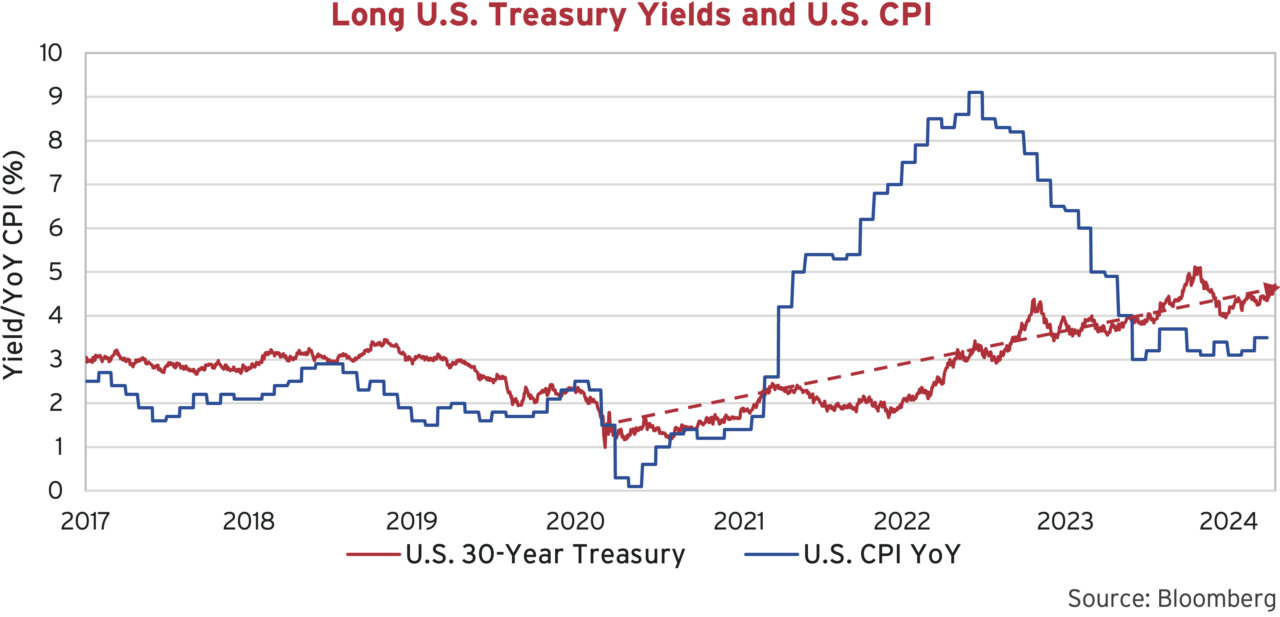

There has been a steady march upwards in long U.S. Treasury (UST) yields from the bottom at 0.88%, intra day low, in March 2020 at the start of the pandemic to the current 4.7%. As the narrative turns from the “Back to the ZIRP Future” to “Higher for Longer” for both interest rates and inflation, the sharp enthusiastic drops in yields are followed by longer periods of yields creeping higher, as the chart below shows.

The most recent trend, powered by unexpectedly high CPI reports over the last several months, has been higher, but that just continues the trend upwards as shown by our dashed line. The good news is that the long UST yield of 4.7% is higher than the current 3.5% CPI. As the risk of higher inflation grows, we would expect investors to continue to seek higher yields on their bonds. That eventually will get translated into the funding of consumer and business debt, so we think things should weaken economically. As we said above, if U.S. yields rise, we think Canadian yields will be under pressure upwards, and Canada has a higher economic risk in this scenario.

Residentially Exposed

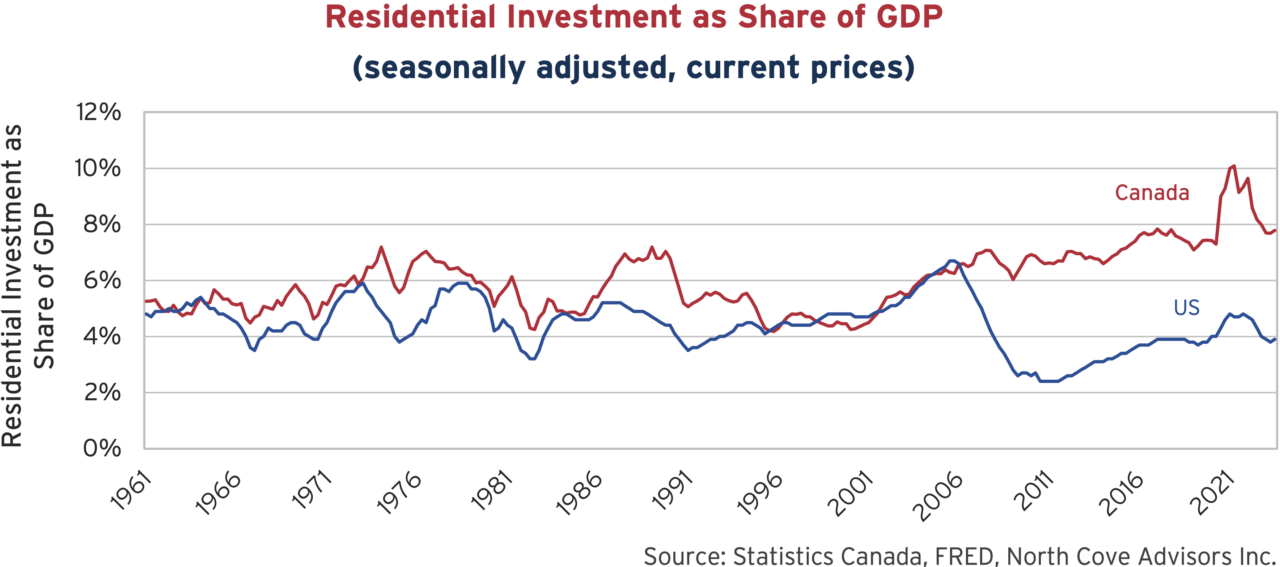

As Canadians piled their savings and capital into one of the world’s most expensive housing markets, making it even more expensive due to their enthusiasm, more and more of their employment and income became dependent on that choice. The Canadian economy used to be similar to the U.S. in its exposure to residential real estate as a share of GDP, as the chart below shows. From 1960 to the Credit Crisis of 2008, Americans and Canadians invested between 4 to 6% of their economies in residential housing. That increased to 6% in the lead up to the Credit Crisis, which was caused by sub-prime mortgage investment mania in the U.S.

From that point, things diverged. The U.S. tightened up its residential mortgage rules, but Canada did the opposite and opened the mortgage credit floodgates. The U.S. housing bubble burst and the GDP share of residential investment dropped precipitously to just over 2%. In the same time period, Canada increased its share to 8%, which soared to 10% during the pandemic housing bubble. After that, Canada has dropped back to 8%, double the current 4% of the U.S.

All In on Housing

As we said at the time, the Canadian government used the Mortgage Insurance Protection Program (MIPP) to give the Canadian banks liquidity. This “Get out of Jail” liquidity pass also gave Canadian financial institutions risk free profits that they were very quick to exploit. Why not increase government guaranteed mortgage lending and its risk free profits to increase your share price and bonus?

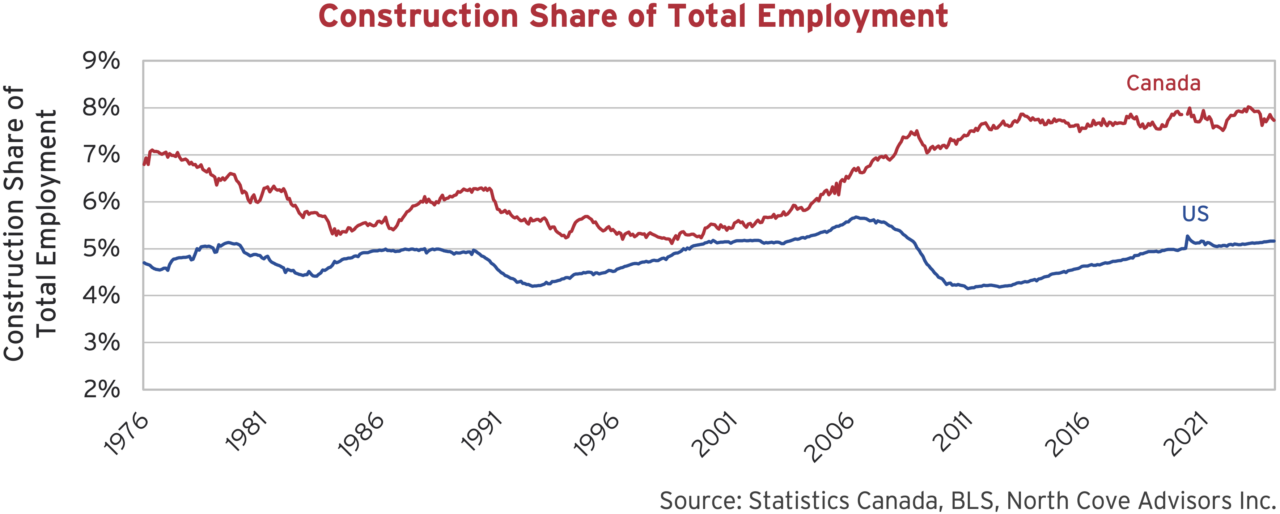

The Canadian banks went “All In” on residential housing and massively expanded their mortgage lending, courtesy of their government’s backing. While Canadian regulators and banks celebrated their financial prowess at keeping the Canadian banking system sound, their hubris created a Canadian economy more dependent on residential housing than any time in our history. The U.S. has just over 5% of their workforce in construction, and we Canadians now have close to 8%, as the chart below shows.

That’s a problem for Canada since the housing market is quickly retrenching after its Covid Bubble. Including ancillary employment such as real estate agents, mortgage brokers, lawyers and bankers and those employees dependent on the housing market, that figure approaches 18% of Canadian employment. With housing sales approaching the lows in 2009 after the Credit Crisis, we think things will be quite a bit weaker in Canada compared to the U.S.

No Return to ZIRP

If the Federal Reserve and the Bank of Canada were to ease monetary policy substantially on tamer inflation, we believe that would “normalize” their yield curves. In the U.S., with the UST currently at 4.7%, a drop in the CPI towards the target 2% would put the real yield (nominal yield minus CPI) at a historically reasonable 2.7%. Canadian long bond yields would be held up towards those in the U.S., making their current 3.6% more than a little optimistic in our view. Short rates would likely plunge as investors piled into short bonds, but we don’t expect any developed country central bank to go back to zero interest rates, however dire the economic climate. A return to the ZIRP regime is highly unlikely for any central banker after their shock from the out of control inflation in the aftermath of the Covid pandemic. That means that short rates probably have a bottom end of 2 to 3%, a 0 to 1% real yield on T-Bills. That would make for quite a stimulative yield curve, as long bond yields were held up by concerns about lax monetary policy allowing higher inflation. Indeed, the worst case for longer bonds would be the Fed acting on its current musings that it could ease even if inflation were to stay elevated and above its target. That would certainly risk investors deciding that central banks really didn’t mind higher inflation and send yields higher accordingly.

Neuter-aling ZIRP

If Canada ends up considerably weaker than the U.S., and we believe this is quite likely, we think an easing by the BOC would not approach ZIRP’s “zero bound”. The potential for an inflationary currency depreciation means that a floor on Canadian T-Bills similar to the U.S. would be likely as well. Recent developments are not helping. In the recent BOC statement, their “neutral” policy rate, was raised by 0.25% from 2-3% to 2.25-3.25%. This is the BOC fund rate that the BOC believes is neutral for the economy, neither stimulating nor lessening economic activity. This move by the Bank of Canada suggests to us that ZIRP is dead and gone. The mid-range of neutral has now moved up from 2.5% to 2.75%. That probably puts a bottom bound of 3% on interest rates unless inflation drops precipitously or the economy experiences dire recession. With the current yield of the 5-year Canada at 3.8% and the 30-year at 3.6%, we think there will be a lot of disappointment when the BOC finally moves. As they say about life, sometimes the anticipation is more pleasurable than the eventual experience, which often disappoints.

Canadians’ Bleak Mortgage Future

We have another worry about Canada, that concerns the structure of our mortgage market. Canada has short mortgage terms of mostly 5-years and less, with 25-year amortizations that are due and payable when their term ends. Canadian mortgages also have prepayment penalties. Even if a Canadian homeowner locked in the lowest 5-year mortgage rate of 1.4% available in December 2020, they would get refinanced at 4.8% if current rates hold into 2025. That’s quite the shock.

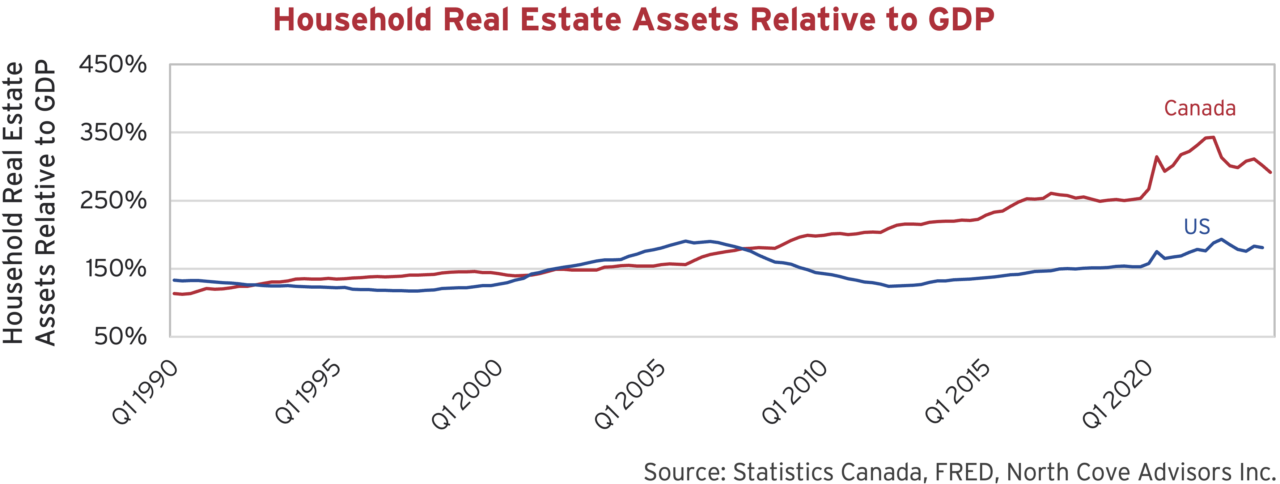

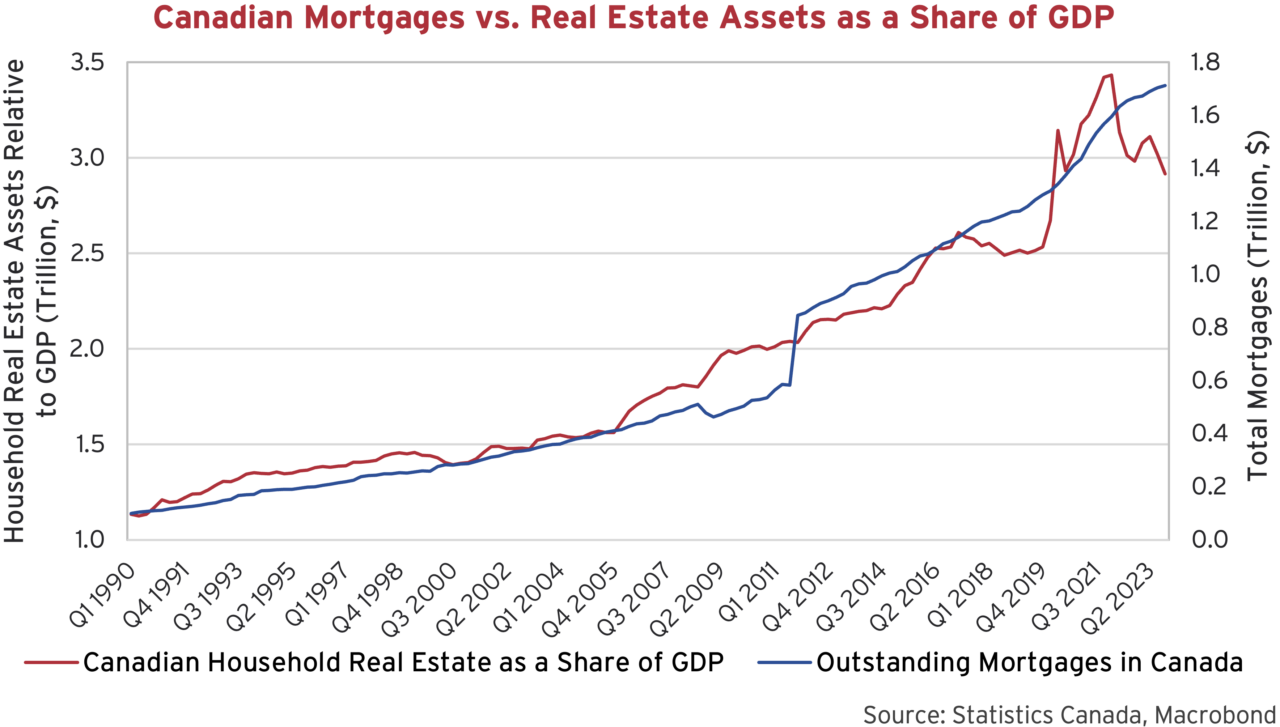

We all have read that Canadians are some of the most indebted consumers in the world. A large part of that debt is residential mortgages and that finances much of our Canadian wealth, tied up in our houses, as shown in the charts below. We note that the ideas for these charts come from Ben Rabidoux of North Cove Advisors, who we highly recommend for solid information on the Canadian housing market. Household real estate assets are close to 300% of Canadian GDP, compared to under 200% in the U.S.

Mortgage Windfall for U.S. Homeowners

In contrast, the U.S. has mostly securitized 25-year term mortgages that have no prepayment penalties so there is an incentive to refinance if mortgage rates decline. American mortgage brokers have taught their clients to renew when mortgage rates fall, and very few mortgages aren’t refinanced when it is attractive to do so. That means many, if not most, U.S. homeowners have mortgages they locked in at the very low rates during the pandemic, 2 to 3% below where they currently are. American homeowners have a financial windfall compared to their Canadian neighbours. That’s why the U.S. housing market is very slow and prices might be staying high, as homeowners can’t port their mortgage windfalls to new properties and prospective purchasers confront mortgage rates far higher for properties of the few sellers who must sell for non-financial reasons like employment, divorce, or death.

Breaking Bad Break Evens

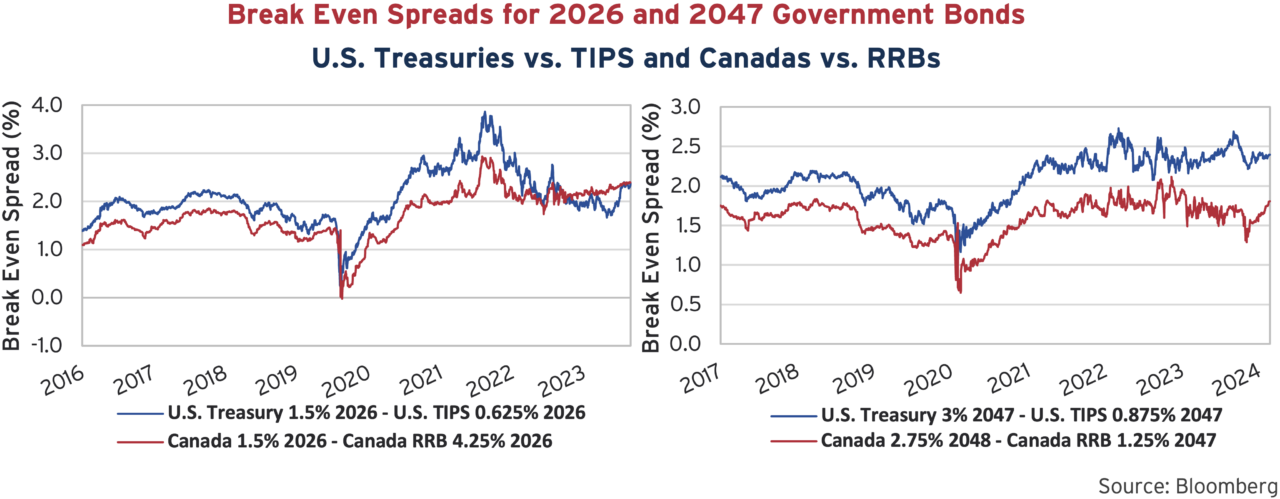

The bond market consensus now is that inflation has come off its highs and is well on its path to normalcy and the central banks’ 2% target. This is challenged by the current reality of the most recent inflation reports. That said, the impounded bond market estimate via inflation-linked bond Break Even Spreads (BES) generally seems to be increasing of late for both Canadian and U.S. inflation-linked bonds. As the charts below show, market inflation expectations are on the rise. The 2026 BES on both Canadian RRBs and U.S. TIPS has moved up to 2.4% from 2% over the last year. The 2026 and 2047 BES are the same at 2.4% in the U.S. The Canadian RRB 2026 BES is the same at 2.4%, but the 2047 RRB BES is lower at 1.8%, albeit moving up sharply from 1.4% in the past few months. From December 2018 to present the correlation is 97% between U.S. and Canadian CPI, the long end of the Canadian curve seems to be mispricing future inflation.

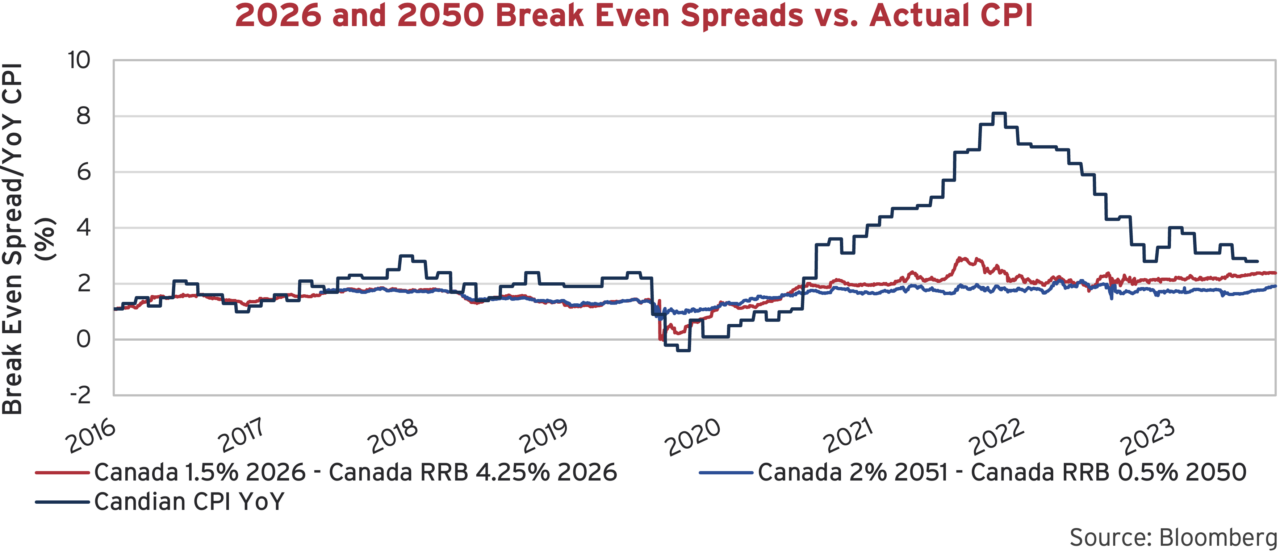

Denial of CPI Attack

Since we believe we might see greater economic weakness in Canada, we’ve plotted the BES inflation estimate for the 2026 and 2050 RRB versus actual experienced Canadian CPI. You will note the actual CPI ran higher than the BES from 2017 to the outbreak of the pandemic in 2020, when it dropped below. Actual CPI then surged above the 2026 and 2050 BES in 2021. It took quite a while for actual inflation to peak and then drop, but the BES never breached 3% and soon reverted to a more moderate 2%. That showed bond investors’ confidence in a return to “normal” towards the 2% BOC target.

A Question of Confidence

The recent increases in the market’s inflation estimate incorporated in the BES is concerning. The important question for a bond investor is what your bond will be worth in terms of current dollars at maturity. Higher inflation depreciates the future value of a bond and makes bond investors demand higher yields to compensate for their loss of purchasing power. Bond investors were comfortable with assuming a 2% inflation rate prior to the pandemic, as they were confident in central bank’s ability to keep their inflation risk low. The unprecedented monetary stimulation during the pandemic and the subsequent highest inflation in 40 years challenged that confidence and the prior beliefs of investors.

Back to the Inflation Future??

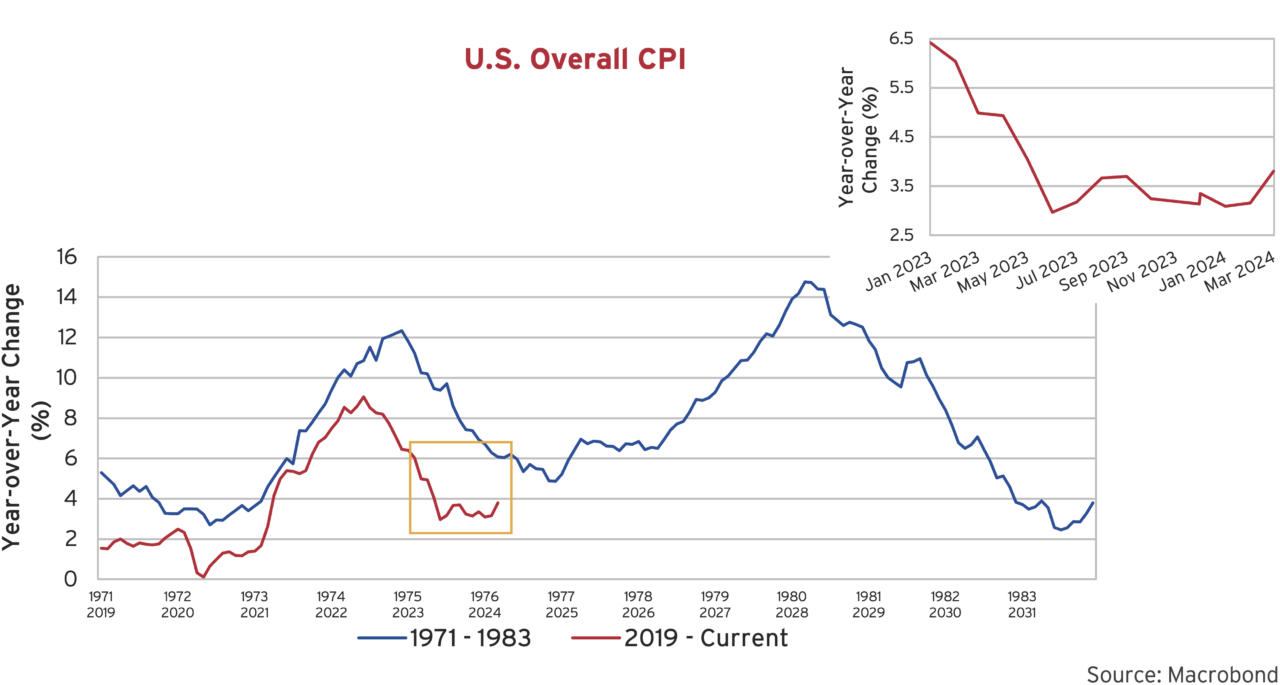

We’ve been here before, at least those of us who were around in the 1970s. We created the chart below, which we’ve shown you before, to show the problem the Federal Reserve and other central banks face. We’re impressed that we’ve seen this used by commentators much more impressive than your suburban Market Observers from the beautiful Hills of Richmond since then. The blue line is the U.S. CPI for the 13 years from 1971 to 1984, which is the high inflation period that started with the Arab Oil Shock in 1973. Oil prices shot up by nearly 12 times from $3.35 to $39.50. This was an exogenous political event, a furious response by the Arab Oil producing countries to the massive military support of Israel by the United States during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. The Federal Reserve and other western central banks responded by immediately loosening monetary policy so their economies wouldn’t grind to a halt. That worked, but the U.S. CPI soared as that monetary accommodation provided the dollars for consumers and businesses to pay the higher energy prices. It also provided the fuel for higher prices for other goods and services, so inflation soared from 3% in 1972 to over 12% in 1975.

The Fed then aggressively tightened monetary policy and the U.S. government applied wage and price controls that brought the CPI back to 5% by 1977. That was when the Fed eased policy and dropped interest rates, only to see inflation then soar once more, to over 14% before the Volcker Fed tightened monetary policy and raised rates to unprecedented levels to battle inflation. That engendered the severest economic setback and recession since the Great Depression of the 1930s, but it eventually tamed the runaway inflation of the late 1970s. The mantra of that period was the strict monetarist “only money matters” for central bank policy.

Lessons Hopefully Learned

The current situation is eerily similar. The red line shows CPI soaring in 2021 to 9% and dropping in 2023 to the 3% range, as the Powell Fed aggressively raised interest rates. It now seems stuck in the 3 to 4% range, well above the 2% target, especially after the recent U.S. CPI showed resurgent price increases for March. The inset graph from December 2022 to present shows the U.S. CPI bottomed just below 3% in June 2023 and now seems to be on the rise towards 4% once again. This is what the Fed and the BOC are worried about.

The current Fed, like its predecessor in 1976, is under immense pressure to ease monetary policy and lower rates. Every time there is a weak economic or inflation statistic, the clamour grows for the Fed to relent. Jerome Powell and the Fed Governors know the lesson of that period is that the Fed loosened monetary policy too early, and ended up with inflation that once again took off, to even higher levels.

Mortgaging their Economic Future

Canadians, bond managers and houseowners alike, have been waiting with anticipation for what they consider an inevitable drop in interest and mortgage rates. The recent stronger inflation numbers in the U.S. are questioning that consensus. As we said earlier, those used to the ultra-low interest rate environment of years past are likely to be disappointed in their new reality. Historically, it is very unusual to have the BOC rate and bond yields under inflation, but this was the case in the years of ZIRP after the Credit Crisis.

Again, we think there is more potential weakness in the Canadian economy due to our mortgage market structure but also the extent of floating rate mortgage debt. When interest rates bottomed in 2021, the floating mortgage rate was considerably lower at 0.9% than a fixed rate 5-year at 1.4%. Canadians flocked into these lower rates, especially since banks provided structures that mortgage payments wouldn’t go up with rising rates for the term of the mortgage. That caused a large share of Canadians with mortgages to go floating rate, estimated at the peak just shy of 35% of total outstanding mortgages, homeowners who chased the lowest mortgage rate. This financial product innovation backfired, and many of these floating rate mortgages have grown in outstanding principal, lengthening their amortization by many years. As the Toronto Star reported,

“During the Bank of Canada’s rapid rate hike campaign, fixed-payment variable rate mortgages gained attention as some homeowners’ amortizations were automatically extending out to as long as 90 years. In some cases, people received infinity symbols on statements making it seem like they had “forever mortgages.” 1

Now the mortgage preference is for fixed rate, with the 5-year at 4.8% compared to the floating rate at 6%, due to the inversion of the yield curve. Canadians renewing their mortgages are throwing in the towel and choosing to lock in lower fixed rates when their current term is up. That means that, as floating rate mortgages are replaced with fixed rate mortgages, the effect of lower rates might not be as powerful this time around.

Ultra-Low Expectations for Credit

As we have been saying for some time, it is shorter bonds that look attractive to us, given the unrealistic hopes built into longer yields. Lower quality credit continues to look expensive to us, as investors stretch for yield and the compensation doesn’t justify the credit risks assumed. Given all the debt that was issued at ultra-low interest rates, we think it is not the time for accepting low yield spread compensation on risky assets. The credit excesses of the ZIRP period are only now being recognized. As loans and bonds issued during the ultra-low rate period mature, we are expecting credit mayhem.

Privately Terrified

At Canso, we have spent much of our careers as credit professionals in the debt markets and what we have seen for the past ten years of ultra-low rates concerns us greatly. The most unsuspecting investors usually end up holding the dodgiest investments at the end of every credit cycle. This cycle, the advent of passive ETF investment in bank loans and high yield, Collateralized Loan Obligations, derivatives based on credit indices and the marketing of opaque Private Credit have commoditized risk and made things even more risky. In the current credit markets, the professionally inane portfolio managers of these private and passive investment vehicles don’t think by design but have to buy and sell depending on the cashflows in and out of their funds. When the money poured into these funds, the money was invested, for better and mostly worse, in whatever was on offer.

Don’t Bank on Your Loans!!

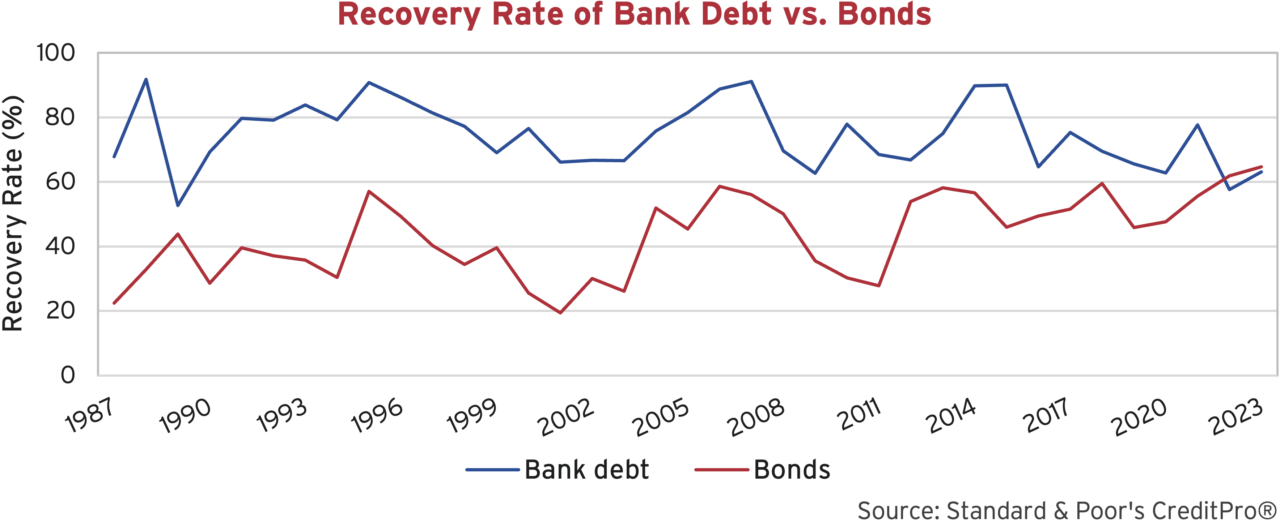

For example, the result has been that the issuer quality, covenants, and the security of secured bank loans has been thoroughly debauched during the ZIRP credit orgy. Historically, the recovery on bank loans was far higher than public marketable bonds. As you see in the chart below, now it is virtually the same, as banks lowered their credit standards to compete in the credit palooza of zero cost capital.

Creditor on Creditor Violence

As old credit analysts say, “security and covenants don’t matter until they’re all that matters”. A Bloomberg article entitled “Tech’s Cash Crunch Sees Creditors Turn ‘Violent’ With One Another” is a good example of the consequences of the laxness in the credit markets during ZIRP:

“Alvaria Inc., GoTo Group Inc. and Rackspace Technology Inc. are among a spate of troubled tech companies to agree to restructuring deals this year that provide select lenders with better terms on debt swaps than others, a process sometimes deemed a form of ‘creditor-on-creditor violence’… It’s part of a wider trend of heavily-indebted corporates looking to manage their liabilities by taking advantage of relatively loose agreements with debt investors — known as covenants — that can allow them to move assets out of the reach of creditors. Typically, firms threaten to do so because higher borrowing costs combined with excessive leverage have left some with balance sheets that are impossible to refinance, said Jason Mudrick, founder of distressed credit investor Mudrick Capital… “These two phenomena, coupled with the covenant-lite nature of leveraged loans today, have been the primary drivers of the creditor-on-creditor violence we’re seeing,” he said.” 2

As you can see from the behaviour above, rather than making the credit markets more efficient, the advent of mindless investing in credit actually makes things idiotic. As we’ve told our clients many times, at least with equity indexing, the investor is rewarded by having a larger weight in stocks of companies which are doing better. The credit indices give higher weights to issuers that create the most debt. That is not what we think is a recipe for lending success. On the other hand, it gives active credit selection a definite advantage over these funds.

A Long and Grinding Road

We apologize for the repeated thoughts and content from earlier editions, but we are in the fortunate position of having some of the things we thought might happen, actually happen. Sometimes thinking from the bottom up and knowing investment history actually pays off. Our conservatism in the face of market ebullience risks us being left behind less cautious portfolio managers but that’s a risk we welcome if our valuations don’t justify the risks we would assume.

It now seems risk and downside might be raising its ugly head once again. As we go to press, the consensus seems to be shifting towards “higher for longer” for interest rates. Another Bloomberg article entitled “Risk-Addicted Wall Street Funds Are Shaken as Bad News Piles Up” caught our eye:

“Just weeks ago, it all felt so easy. Jerome Powell was poised to kick off the great monetary pivot in earnest thanks to the steady demise of inflation, while Corporate America’s famous profit machine vindicated the euphoria on Wall Street and beyond… Now after a week of geopolitical tensions and bond volatility, life is getting harder for money managers who are sitting on some of their highest exposures to stocks and credit combined in a decade.” 3

We can assure you that we are not a “Risk Addicted Wall Street Fund”, and it didn’t feel easy to us. It felt like the markets were making a sharp departure from reality. We are not on Wall Street or Bay Street or in any financial district, but rather suburban Richmond Hill. Our portfolios are the most conservative they’ve been in many years, so we don’t have “the highest exposures… in a decade”.

In contrast to the pandemic and the various financial crises where foolish financial institutions were rescued by central bankers, this time just might be different. Those financial crises were short and sharp corrections and powerful rebounds. This time we fear it might be a “long and grinding road”, to paraphrase the Beatles. That means we’re prepared to weather difficult markets and to then take advantage of value opportunities that present themselves.

If you’re not paid well enough to assume a risk, don’t take it!!