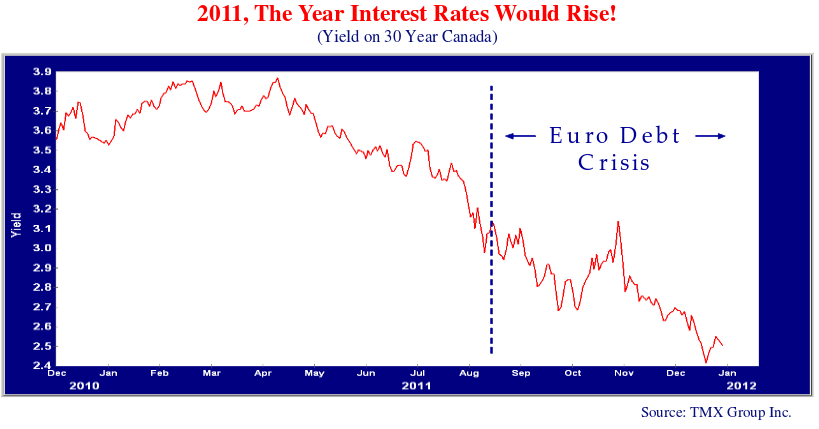

2011 was the year, it was unanimously agreed, when interest rates would finally start to rise. Bond media personalities lectured and hectored the world on the low level of yields and the obvious investment insanity of owning bonds. The problem was, as is shown in the chart below, bond yields fell dramatically in 2011 and proved the investment talking heads wrong once again. As always, the consensus for higher interest rates existed to give investors a place of psychological comfort to share with the investment herd. As is quite often the case, this investment place of comfort proved very uncomfortable as things turned out far differently than the shared expectation.

Rebooting Bonds

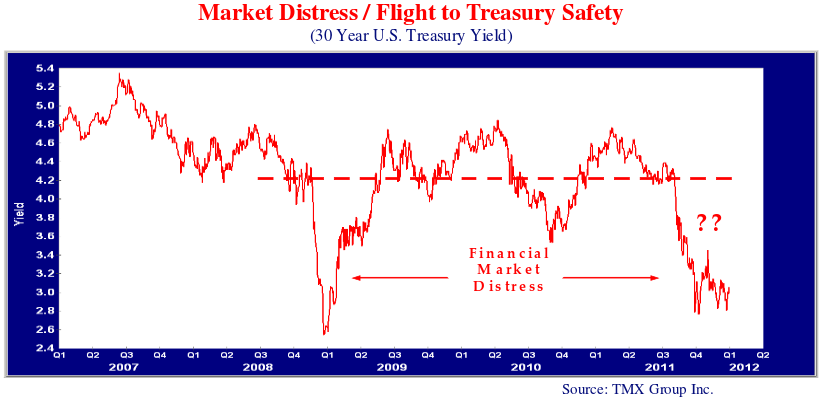

Interest rates defied this tight consensus and fell dramatically in 2011. As can be seen on the chart above, the 30 year Canada yield began the year at 3.6% and ended the year at 2.5%! Yields began their decline in May and accelerated with the euro debt crisis “flight to safety” in August. Bond managers then scrambled to “reboot” their strategies and spent the rest of the year trying to get their portfolios longer in term.

A Fine Bond Vintage

2011 turned out to be one of the best years for Canadian bonds in quite some time. The DEX Universe closed the year with a total return of 9.7% which is the best year since 2000. Long-term bonds were the place to be, with the DEX Long Term Bond Index up 18.1%. The DEX Corporate Bond Index lagged its government cousins with an 8.2% return versus 10.2% for the DEX All Government Index. The 13.1% return of the DEX Provincial Bond Index outperformed the Universe by 3.4%, showing the benefits of its longer duration in a declining yield environment.

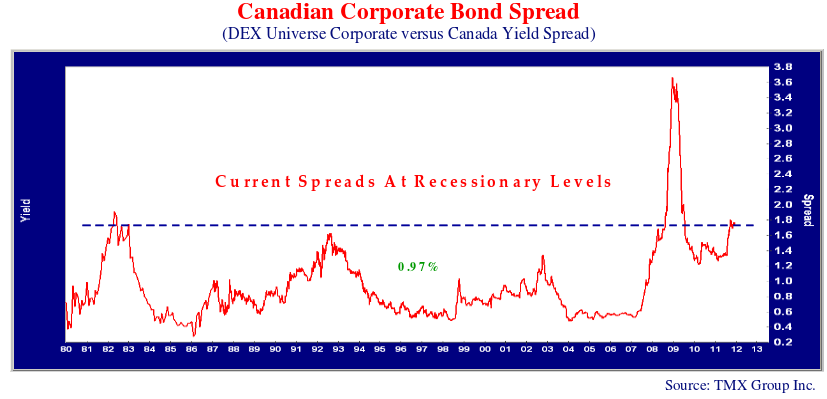

Spreading Bond Risk

Credit was not a place to be as investment dealers and banks reduced inventories. As the chart above shows, credit spreads widened in 2011 from their already elevated level at the end of 2010. Risk assets sold off as the European debt crisis flared up anew in August as a result of the Greek debt restructuring negotiations. The German insistence that private creditors take a loss on their Greek government bonds as part of the restructuring of Greece’s debt unleashed a wave of worry over the solvency of Europe’s banks. European banks hold large amounts of sovereign debt. Once the possibility of losses on these holdings arose, investors began to worry about the state of European bank balance sheets. The regulators added to the uncertainty. In a vain attempt to restore confidence in Europe’s banks, the European Banking Authority (EBA) conducted stress tests which involved markdowns on troubled European sovereign debt. This only added fuel to the fire as many banks were declared to lack sufficient capital. Finally, in December, the euro zone leaders announced that no other sovereign debt restructurings would force private creditors to take losses. This was too late to make much of a difference.

Punished Banks

The problem now is that the market is punishing banks for any holdings of euro government debt. After the debacle of futures broker MF Global, which went bankrupt after making a bet on euro sovereign debt, banks are selling down their holdings which adds further downwards price pressure. European sovereign debt crumbled under the pressure, as did European bank bonds. The market’s muscle memory of the recent credit crunch spread the euro zone problems to other global banks. Inter bank funding saw the strain and financial yield spreads widening to post credit crunch highs.

Selling Begat Selling

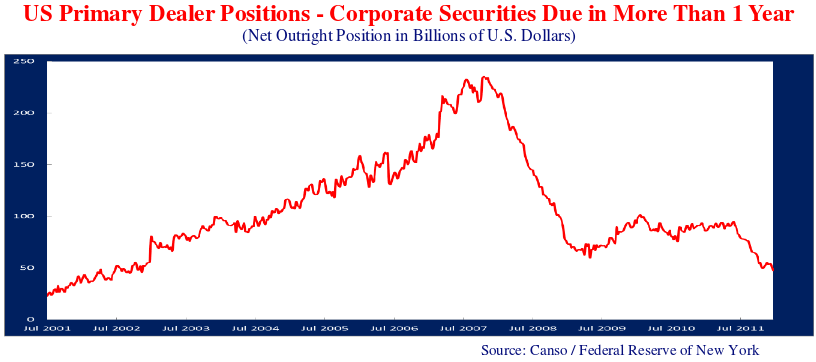

Once again, investment banks pulled in their “risk aggregates” and sold their corporate bond inventories so non-financial yield spreads widened as well. Federal Reserve Bank of New York data show that both the corporate bond inventories and the short term liabilities of banks have dropped in 2011. As it became more difficult for banks to finance in the commercial paper market, they responded by selling off their inventories of longer term corporate securities.

“These precautions have led to dramatic reductions in bank exposure to short-term liabilities, particularly at foreign banks, Fed data show. In turn, banks have slashed inventories of corporate bonds to a nine-year low and have significantly reduced the level of financing available to institutional clients for the buying and selling of corporate securities, exacerbating a steady decline in market liquidity this year, according to market participants”. LCD News/ S&P December 30, 2011.

The increased leverage of financial institutions in the credit bubble and the subsequent drop are shown rather dramatically in the chart above. As we show, the major money centre banks reporting data to the New York Fed had only $47.5 billion of inventories of corporate bonds on December 21st, compared to $95 billion earlier this year in May. This compares to $235 billion before the credit crunch in 2007. Revised risk management, regulatory pressure and the curtailing of proprietary trading under the Volcker Rule have all combined to reduce the ability and willingness of banks to hold inventories of corporate bonds.

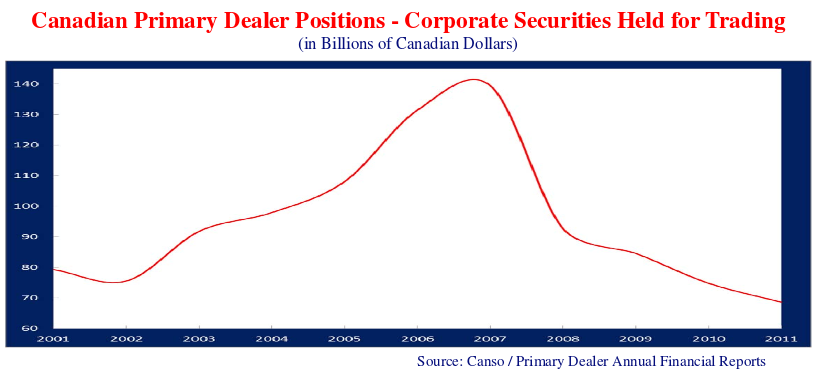

The Flaherty Put

The Canadian corporate bond market was not spared the pain of dealer liquidation, as shown in the following chart.

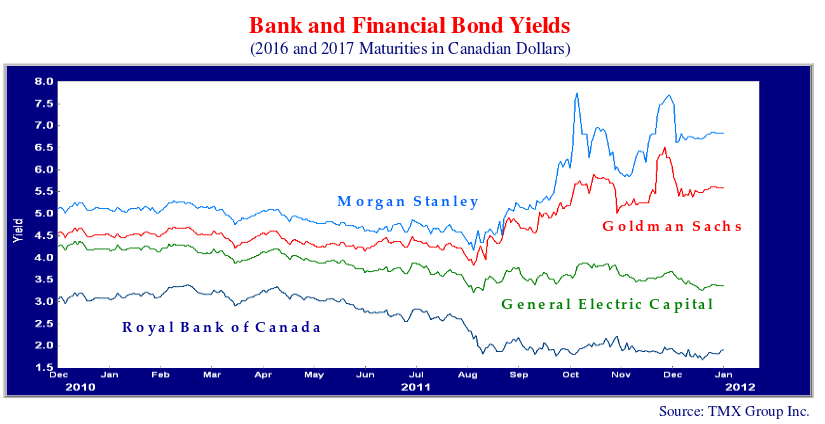

The chart below shows that credit spreads on financial bonds rose in the quarter. The large investment bank and swap dealers saw the most concern as investors questioned their exposure to European financial distress. Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs saw their CDS and bond spreads moving 25-50 bps daily on the latest euro concern. Canadian bank bonds did much better than their U.S. and European peers as Canadian senior bank bond yields stayed 2% to 3% under their international peers. The low level of exposure of Canadian banks to European sovereign debt was comforting to the market. They also benefitted from the “Flaherty Put”, the ability of Canadian banks to shift all of their mortgage risk at any time to the Federal government through CMHC secondary mortgage insurance programs. One might wonder what will happen when the overheated and overvalued Canadian housing market finally starts down, but this was not a market concern.

The Lowest Yields since 1945!

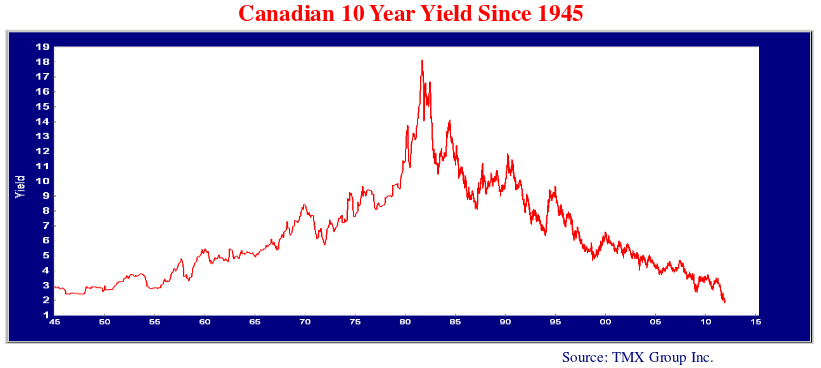

Looking forward into 2012, the level of yields on Canadian government bonds is now historically very low. This can be seen in the following chart with the yield of the 10 Year Canada which finished 2011 at 1.9%, lower than any time since 1945! So what should we make of the current ultra low level of yields? Is this the “new normal” for the foreseeable future? To us, the answer lies in the “real” answer. How likely are yields to stay this low given the prospects for the economy, inflation and monetary policy? Like the 1930s Depression, we have debt liquidation and a deleveraging which is impacting financial asset prices and prospects. The difference is that we have what is at the very least an ultra expansive monetary policy in most developed countries. Even Europe, with the ECB taking flak for not monetizing euro sovereign debt, has very accommodative policy and has added to this with its new 3 year term lending facility.

One thing that gives us pause is the current political imperative for fiscal probity and economy. The questionable “conservative” fiscal policy of the 1930s, which is widely thought to be a major contributor to the severity of that economic contraction, has now been reborn as “Tea Party” economics in the United States. This conservative economic philosophy is one of the reasons for the current euro debt crisis. The Germans and their northern European neighbours are insisting on fiscal discipline in Greece and the other indebted euro zone countries. It is very difficult to grow out of a recession with governments slashing expenditures and banks reducing their lending.

A Tight Consensus

So, do these celebrated macro issues mean that bond yields have only lower to go? Are the developed Western nations and Canada reprising the Japanese deflationary spiral? The bad news is well known. At the outset of 2012, we have the rather unanimous consensus that Europe is destined for a bad outcome, if not a complete breakdown of the euro zone, and the markets are in for substantial volatility. Risk assets are out and “safe” government bonds, U.S., German, British, Japanese and Canadian, are in. Investors seem to forget that the U.S. was downgraded from AAA and that suspect France is still AAA.

The good news is that this “tight” consensus is adhering just as blindly to this present worldview as it was to rising interest rates and inflation at the start of 2011. Just as the markets priced in rising inflation and interest rates last year, we think the markets have priced in a lot of the negatives. Our sneaking suspicion is that the euro will survive another year and complete financial Armageddon just might be avoided. If this indeed happens, contrary to market expectations, interest rates just might confound the consensus once again and rise in 2012 as they were supposed to in 2011.

Undropped Yields?

In terms of how far interest rates could rise, the previous chart of the U.S. long Treasury yield shows just how much they dropped in 2011’s euro debt crisis. They dropped from 4.2% in August to the current 2.8% at year end. Any resolution of the current predicament short of absolute disaster argues for long yields to return towards 4%, as they did after the credit crisis of 2008-09.

The U.S. economy seems to have defied the skeptics and improved in the latter part of 2011, despite the financial crisis headwinds. Canada continued to grow but weakened in the latter part of the year. As opposed to virtually everywhere else globally, Canadian residential real estate continued to increase in price in 2011. With the Governor of the Bank of Canada, Mark Carney, lecturing Canadians on record setting debt accumulation, we think the Canadian credit based real estate miracle is setting up for a reverse. As we have said many times previously, the boom in Canadian housing prices has more to do with the huge assumption of credit risk by the Federal Government through the CMHC than with any intrinsic value increase.

The House of Unrealistic Actuaries

While it is now true that Canada’s banks can offload their mortgage credit risk at will to the unsuspecting CMHC, this would probably change if losses developed. As the U.S. experience of mortgage insurers shows, the actuarial assumptions on housing losses are very low and unrealistic when prices are rising. The actuarial experience sours when prices fall and loss provisioning becomes very pro cyclical. The huge capital requirements for CMHC in a loss scenario could become a political millstone that could see the mortgage guarantees of CMHC cut back at the very time when the housing market was the weakest. How many banks would want to renew mortgages at very low interest rates and very high appraisals if they had to accept the credit risk themselves? Like the current situation in Europe with sovereign debt and in the U.S. with residential mortgages, a reduction in bank willingness to extend credit adds to further price declines in the asset in question.

Implausible Deniablity?

Given the economic headwinds, we think it is very unlikely we will see an aggressive tightening by the Bank of Canada for the foreseeable future. The very public lecturing on consumer debt by Mr. Carney gives him the benefit of “plausible deniability” for the current credit excesses. We think it would take a considerable increase in Canadian inflation for Mr. Carney to actually increase Canadian interest rates. Longer term rates are another matter, as they follow international developments. Canada has benefitted from its sound financial reputation and investor and central bank “safe haven” bond purchases but this could reverse with a weakening of the Canadian economy.

Really Expansive!

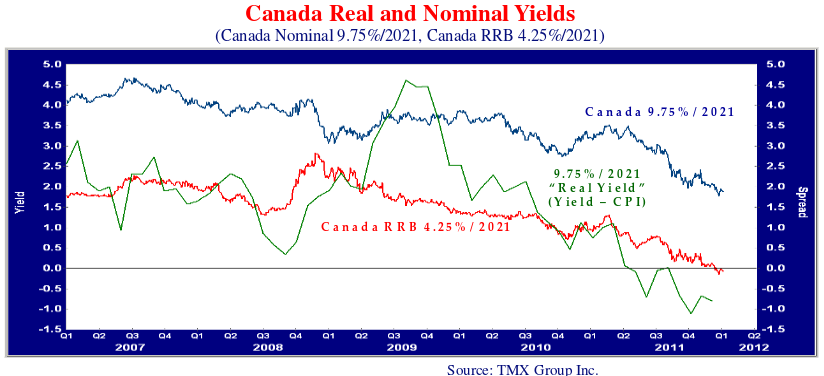

Just how expansive is Canadian monetary policy? Judged by real interest rates, it is very expansive. The previous chart shows the yields on the Canada 9.75%/ 2021 (blue line) which has fallen from 3.5% before the euro debt crisis to the current 1.9%. The Canada Real Return Bond (RRB) has seen its real yield fall from .8% pre-crisis to the current -.1%. This means an investor accepts a negative yield in real terms and gains from the future increases in inflation. The “real yield” on the Canada 9.75%/ 2021 is more negative. This is calculated by taking the yield on this bond of 1.9% and subtracting the current 2.9% CPI to get the negative -1% “real yield”.

In terms of inflation, Canadian government bonds have seldom been more expensive. Either yields have to rise 1% or inflation has to fall 1% to give investors at least a positive real yield on their Canada holdings. In our view, now that the consensus has formed that inflation and yields will stay low “for a protracted period”, as the Fed puts it, they both just might rise.