The Gomer Pyle Economy

“Surprise, Surprise, Surprise!” said 1960s television character Gomer Pyle enthusiastically in his strong southern accent when confronted with something very different or unexpected. While Gomer has been off prime time TV for some time, the financial markets are doing their best to live up to Gomer’s saying in the first quarter of 2006.

The major stock indices have had, to quote CNNMoney.com, “one of the best first quarters for the major gauges in years”. The Dow Jones Industrial stock index had its best first quarter since 2002. The broader S&P 500 index had its best first quarter since 1999. The tech laden Nasdaq index had its best first quarter since the peak of the dot.com boom in 2000 and is reaching new highs. The U.S. economy continues strong with the first quarter employment and manufacturing statistics powering up substantially from the weakness of the fourth quarter of 2005. Internationally, Europe and Japan are also showing economic strength. What ever happened to the fragile economy and financial markets that the critics of the Federal Reserve wanted to protect?

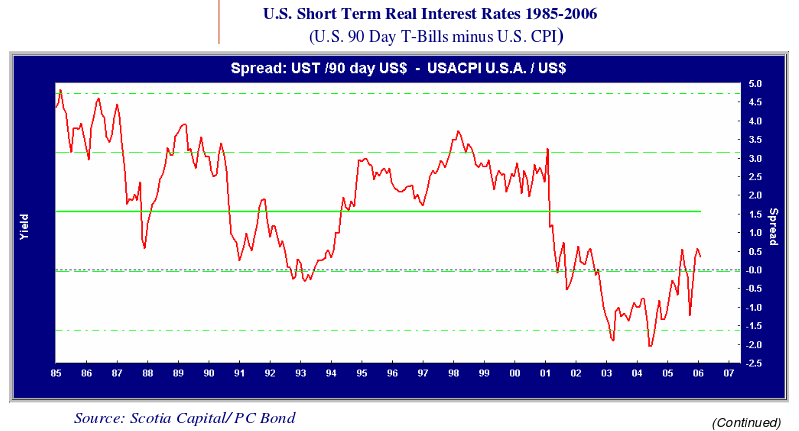

Zealous Real Interest Rates

After 15 short-term interest rate increases by the Federal Reserve, the economic momentum continues in the United States. This puzzles most market commentators but not us. Alan Greenspan, in his zeal to protect the U.S. economy and financial markets, lowered interest rates far below any reasonable level given the economic activity at the time. The chart below shows the real interest rate on U.S. 90 day Treasury Bills over the 1985-2006 period. This chart shows that the average real interest rate was 1.6% over the period. Notably, it shows only two periods of negative real interest rates, where the inflation rate exceeded the T-Bill rate. One of these was in the aftermath of the real estate market meltdown from 1992 to 1993. The other is the current period, starting in 2001 and lasting until now.

While economists argue about the transmission mechanism for monetary policy and the definition of money supply, it is generally agreed that low real interest rates are “stimulative”. This means negative real interest rates are exceptionally stimulative since it means that T-Bill investors receive less interest on their investments than the increase in the price level over a period.

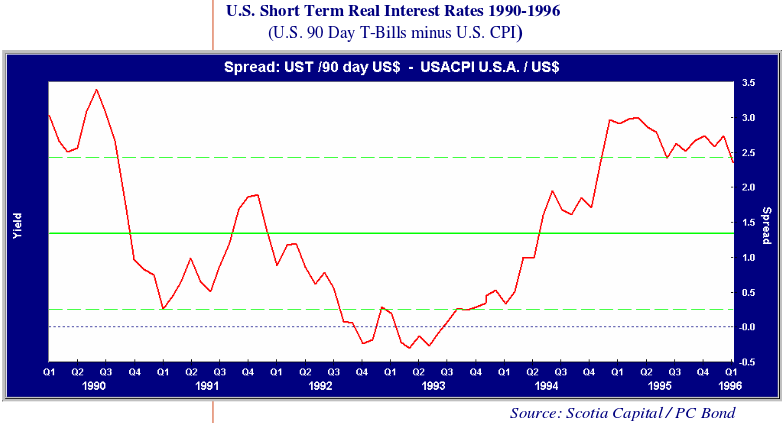

We have isolated the periods of negative U.S. short-term real interest rates in the following charts. The 1992 to 1993 period saw moderately negative real interest rates for a short period of time. Real rates went negative in the third quarter of 1992 and climbed into positive territory a year later in the third quarter of 1993. The average real yield of 1.4% in the six year period from 1990 to 1996 was not too far below the average of 1.6% since 1985.

This short and moderately negative period of real interest rates did not reflect a lack of financial distress over this period. This was the commercial real estate meltdown in the United States where the major U.S. banks were basically insolvent with huge amounts of their loan portfolios in distressed real estate. Saudi Prince Alwaleed bin Talal had to come to the rescue of Citibank which was floundering in its loan losses and had a failed auction for one of its securities.

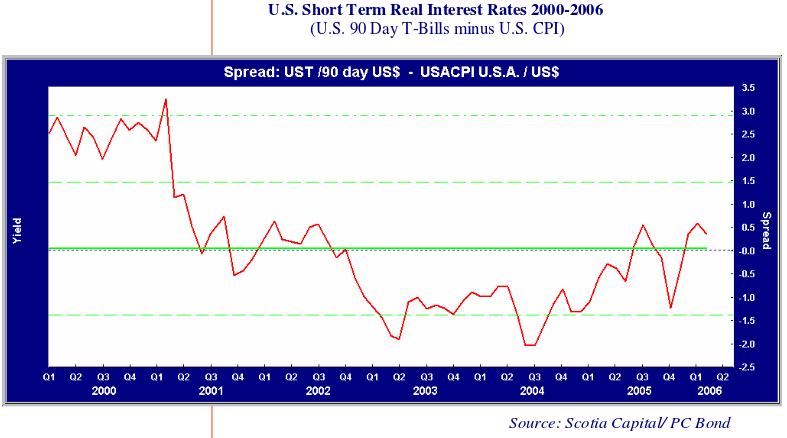

Judging by the real interest rate however, the monetary policy accommodation in this period was relatively modest compared to what we’ve just been through. Looking at the following chart, we see that real interest rates went negative in the second quarter of 2001 and stayed there for more than four years until the fourth quarter of 2005. The average real interest rate for the six year period 1999 to 2005 averaged 0% compared to the 1.4% over the 1990 to 1996 period!

Borrowing in Hyper Drive

Yes, we had the dot.com meltdown, September 11th and the war in Iraq to deal with but one can’t escape the observation that the Fed’s monetary response to these problems was perhaps a little overdone. If the purpose of low real interest rates is to stimulate borrowing, the goal of negative real interest rates should be to hyper-stimulate borrowing. And borrow Americans have, joined by borrowers around the world who have been stimulated in turn by their own central banks and low real interest rates.

This has caused an explosion of asset values as a consequence of the “borrow until you drop” philosophy adopted by consumers and financial market speculators. All financial investments have seen prices rise due to the ultra low level of real and nominal interest rates. Hard assets such as residential housing, investment real estate, oil, gas and virtually all marketable commodities have all participated in this relative price increase versus paper money, especially the financial commodities like gold and silver.

What truly worries us is the aftermath of this monetary stimulation and credit boom that really has no parallel in recent years, if ever. The former Fed Chair, Alan Greenspan, did his best to provide ample warning. Once he got short term interest rates down to 0.5%, he declared that his U.S. economy patient was alive and began to raise rates in a “predictable manner” which has been happening ever since. The message to anyone who cared to listen was to stand clear of financial danger. Unfortunately, no one listened.

Hard to Start, Harder to Stop

Monetary policy implementation and effect is comparable to trying to light a fire with wet wood. A single match is useless against a pile of wet wood. Once fire starter is used however, a single match is more than adequate. It doesn’t really matter that the wood was wet once the fire has been burning for some time. It is still very hard to put out. As we have been saying in our previous reports, the underlying strength in the U.S. economy and the speculation in the financial markets will continue for some time in the face of the measured and incremental changes in U.S. monetary policy and short term interest rates. The tightening trend of the U.S. Federal Reserve is being reinforced by what is happening in Japan and Europe.

Japan has succeeded in its efforts to defeat its deflation with its policy of “quantitative easing”. Given the problems of the Japanese financial system and the malaise in its economy, the Japanese central bank followed up its ultra low interest rate policy with a publicly announced policy of printing money until some inflation reappeared. This has happened recently with a return of positive inflation numbers after years of deflation. The Japanese monetary authorities are now hinting that this policy of shoveling money out the door will now be switched to a more conservative policy of simply targeting a very low level of interest rates. This is causing huge debate in Japanese financial and business circles where many investors and businessmen have only known an interest rate of zero for most of their careers. Japanese politicians and government bureaucrats are waging a war of words against the central bank which looks ready to abandon its quantitative easing policy.

Even the perpetually economically weak Europe now looks to be getting out of its sick bed and joining in the surging world economic party. This has resulted in the European Central Bank alerting its citizens and corporations to the likelihood of interest rate increases which is causing consternation with those Europeans reliant on cheap money for their livelihood and financial success.

The outcry at tightening monetary policy is not unexpected. Those habituated to cheap money don’t want it removed. Like recovering addicts at an expensive clinic, withdrawal is hell, no matter how luxurious the surroundings. Those who have built their lives and wealth on the foundation of cheapened money and easily available credit are very dependent on it for their livelihood and are very threatened at the prospect of its removal.

Nowhere Close to Tight

The previous charts all show that we are nowhere close to tight money at present in the United States. We just went positive on real short term interest rates in the fourth quarter of 2005. Real interest rates in the United States have averaged 1.6% since 1985. This combines with today’s 4.0% inflation rate to make 5.6% short term rates not out of the question. Since monetary policy takes some time to work and central bankers typically overcorrect, a real rate in the 2.0% area might be necessary. This would imply U.S. short rates in the 6.0% range if inflation stays at 4.0%. These are far higher rates than the market consensus currently appreciates.

A Monetary Pause That Refreshed

The central banks of the United Kingdom and Australia embarked on their monetary tightening earlier and are much more advanced in their tightening cycle than the United States. Both of these economies seemed to weaken in 2005 which caused some to believe that their tightening cycles were complete. Contrarily, this pause in monetary policy tightening seemed to refresh both of these economies. Recent employment and housing market data in both these countries are showing signs of strengthening. It shows how difficult it is to put out an economic fire once it has been burning heartily for some time and that the road ahead for the Federal Reserve might not be as “incremental” as is currently thought.

In the 1980s, the economic theory of “Rational Expectations” grew out of the incremental monetary policy of the 1970s, which had allowed inflation to spiral out of control. This theory postulated that only unexpected economic policy shocks would be effective, since expected policy implementation would be thwarted by economic agents who compensated for the expected policies. The current “gradualist” and widely communicated monetary tightening being undertaken by the Federal Reserve would not succeed in a rational expectations world.

The Fed’s gradualist approach is not symmetric. The Fed does not believe in popping asset bubbles but it very definitively believes that its role is to avoid financial distress after a bubble bursts. It is prone to dropping interest rates precipitously to confront financial distress but it is loath to raise interest rates in large jumps. This current approach by the Fed is more a result of Alan Greenspan’s experiences when he raised interest rates aggressively. The stock market crashed in the tightening of 1987, losing 27% in a single day. In the tightening of 1994, rising bond yields caused devastation in mortgage securities and caused the near default of Mexico.

Our problem with the gradualist approach of the Fed is that financial markets seem quite skeptical of its willingness to cause financial pain. John Dorfman, a columnist with Bloomberg News put it best when he remarked that it was curious that investors seem to believe that a monetary tightening could be “painless”.

We are now facing a tightening of monetary policy and rising interest rates on a concerted global basis. This puts the financial markets in a very different position compared to the last five years since the Federal Reserve began its monetary easing and other central banks followed. Eventually, the tightening monetary policy will gain traction and deflate the current boom. The good news is that this should take some time. The bad news is that it will inevitably happen.

In previous cycles, companies took on debt to finance ill-advised acquisitions or leveraged buy outs which invariably ended badly when the predicted cash flows did not materialize. In the dot.com boom, companies with persuasive business plans but no revenues were able to issue equity and high yield debt to their enthusiastic investors. We hate to say it, but we think this cycle is different.

Private Greed and Tremendous Vulnerability

Companies themselves are in fairly good shape with low debt and strong cash reserves. It is investors who are layering on huge amounts of debt to finance very speculative investment portfolios, especially derivative strategies. Institutional investors are also chasing returns in very risky and illiquid investments, particularly hedge and private equity funds. Historically, momentum and speculative investment strategies have been considered the territory of individual investors. This time around, the private investment pools seem to have a lock on complex investment strategies that lack any vestige of common sense.

At a recent conference on real estate sponsored by the Wharton Business School, William Mack of Apollo Real Estate, who survived the early 1990s real estate meltdown, spoke of his concerns with the current U.S. real estate market. Specifically, he is worried about the private equity pools using leverage to finance the equity of projects which have themselves been already leveraged by private equity pools. Since all these private equity pools use leverage to enhance their return potential, the ultimate leverage in these structures is huge. As Mack said: “We have a situation developing in this country (the United States) today where, because of high leverage, there is tremendous vulnerability.”(Knowledge@Wharton Feb. 27, 2006) In a period of low interest rates and rising asset values, the returns have been enhanced by the use of leverage. If rising interest rates impact asset values, the thin equity portions of these deals would be chewed up very quickly.

Primed for Disaster

Recently, our firm discussed setting up a “prime brokerage” account with a major bank-owned investment dealer. This is a brokerage account that allows lending against investments held in the account and is the type used by hedge funds. These accounts are quite practical and allow efficient securities lending and borrowing and cheap financing of holdings.

What truly surprised us was the extent of leverage used in these arrangements. It seems to go above the modest 75% margin on public equity investments in a brokerage account, one must go to the “banking side” where up to 90% margin is available! Of course, the bank values the holdings in the account on a daily basis to be conservative in its lending practices.

At the risk of sounding old fashioned, a 10% equity cushion can evaporate very quickly over a few bad days in the stock market. From the bank’s point of view, this would mean selling down the portfolio to maintain the required equity. It does not take a genius to figure out that the explosive growth of hedge funds means that a serious market setback would cause extensive margin liquidation.

What worries us even more is that many esoteric financial instruments like Credit Default Swaps and Collateralized Debt Obligations are held and margined in these accounts. When there is no liquid market for these instruments, valuations are very difficult. In illiquid markets, large price swings will result from very few distressed transactions which will feed into portfolio valuations. Hedge funds will be forced to sell their liquid investments to meet margin calls and this will feed further into market declines. Given the large hedge fund exposure to commodities, setbacks in oil or nickel prices could result in bond and stock liquidation. We believe the extent of speculation by hedge funds in the recent market run up will be matched by the severity of the liquidation forced on them in the coming downturn.

Private Pools Repeat History

The emergence of private pools of capital such as private equity and hedge funds is not without historical parallel. After the strong run up in the public markets in the United States in the 1920s, the “Trusts” became an important market force. These were pools of capital for the well connected which basically ran up stocks in the public markets and then sold them to the unsuspecting public. The trusts used significant leverage which was one of the causes of the stock market crash of 1929. The strict securities market regulation which was imposed in the 1930s as a response to the stock market debacle was only just dispensed with a few years ago. It is truly ironic that the current growth of hedge and private equity funds was made possible by the repeal of the Depression area securities regulatory structure like the Glass Stegal Act which separated investment and commercial banking. Who says that great grandchildren can’t revisit the financial sins of their great grandparents?